Hello there! 😀

Politics used to be simple. Men who worked in overalls (and their wives) voted for the left-wing party. Men who worked in a suit (and their wives) voted for the right-wing party. Economic self-interest was the only significant divide and if you knew someone’s social class, you knew how they voted.

Of course, it was never that simple. Since mass enfranchisement in Britain, the Conservatives have received a substantial number of votes from the working-class. The history of the Labour Party would be very different without the support of the do-gooding middle-classes who were so influential in its creation and direction. Gender was more complicated than simply husbands and wives voting the same way, with women consistently more likely than men to vote Conservative throughout the 20th century.1

Having said that, the decades following WWII did see elections focusing overwhelmingly on economic issues. However, particularly starting in the 1970s, elections began involving multiple dimensions, with parties advocating for both economic and non-economic policies.2 Long-standing non-economic issues have been things like immigration, the environment, crime and EU integration.3

More recently, distinctive non-economic issues related to identity, morality and societal norms dubbed the ‘culture war’ have risen in prominence.

But, if you’re reading this, you probably don’t need me to remind you of that.

The interesting thing though is that, given their newness, we know very little about whether the specific issues that make up the contemporary culture war (such as statues, LGBT+ representation in popular culture, diversity training, transgender athletes, curriculum diversity, and university free speech etc.) affect voters’ electoral decisions.

Whilst the culture war has caused consternation in elite circles and has increased in awareness within the general public, we don’t have strong empirical evidence for how important these new issues are to voters relative to long-standing issues. This is key because even if agreement-disagreement is polarised on a culture war issue, it doesn’t necessarily mean it matters for vote choice if people care much more about, say, the NHS or taxation.

This is what I wanted to explore.

Do a person’s culture war beliefs override their economic or traditional non-economic beliefs when deciding who to vote for? And are there any specific culture war issues which have a particularly large effect?

If you want to read the academic version of this article, you can access it here.

The Old Culture War

The idea that a culture war in Britain has never been seen before is not true. While there is a strong case that social class has been, until recently, the most important factor in voting behaviour, societal divides based on cultural matters have been evident throughout history.

Competing visions of what is ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ and attempts to enforce a particular morality onto society was evident after the English Civil War. Puritans sought to create a morally austere society, with the attempted imposition of a strictly observant culture through much greater policing of personal behaviour. In contrast, the Restoration of Charles II saw the ‘Merry Monarch’ lifting Puritan restrictions and overseeing a more morally libertarian culture.4

Public debates over sex have repeatedly divided society. The Victorian era saw moral panics over ‘gross indecency’ and ‘sexual deviancy’. The Lady Chatterley’s Lover obscenity trial in 1960 exposed a rift between defenders of morality laws and those supporting greater sexual openness. This continued with Mary Whitehouse’s campaigns against perceived moral decline in the media, particularly the ‘video nasty’ panic of the 1980s. The introduction of Section 28 in 1988 banned the ‘promotion’ of homosexuality in schools.

It’s difficult to find a bigger cultural rift than the Reformation. Protestantism became the state religion and lead to centuries of division between Catholics and Protestants. This remained deeply ingrained and the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829, which allowed Catholics to hold public office, provoked a fierce backlash from those who saw Catholicism as a threat to British national identity.

Although largely in decline, Christian sectarianism has been a key feature of voting behaviour in Great Britain (and, clearly, the feature of voting behaviour in Northern Ireland), particularly in cities with substantial Catholic populations.5 Even within Protestantism, Nonconformity was strongly associated with support for the Liberal Party in the 19th century, while the Church of England has often been called ‘the Conservative Party at prayer’.

The term ‘culture war’ is not even new. It is a translation of ‘Kulturkampf’ which described the 19th-century division between the Prussian government and the Catholic Church about religion’s influence over the state.

The New Culture War

Today’s culture war, therefore, while often presented as a new phenomenon, echos these historical patterns.

What is different, though, is the specific content of today’s culture war.6 These are the issues that gained wider prominence in the early-to-mid 2010s, particularly with regards to race, gender and sexual identity.

In particular, they were different in content to those long-running non-economic issues like immigration, crime or the EU. These issues are generally areas in which elected politicians have the power to control what policies are implemented. For example, immigration rules were passed by politicians and will remain until politicians change them. They may evoke strong emotions, different moralities and polarised attitudes, but responsibility for creating, implementing and changing traditional non-economic policy is clear.

New culture war issues differ in that the responsibility for the start, escalation and conclusion of cultural conflicts is either unclear, occurs within unelected institutions, or is a change to wider societal norms.

Culture war debates involve the symbols that help define society and political culture. For example, altering language (both the specific words used and what language is considered acceptable) or how different individuals, groups and ideas are represented (either how often or how positive). Changes can also be more informal through the public enforcement of social norms which people are expected to accept or face social punishment. Overall, the main pay-off is feeling one’s values are dominant or to redistribute social status.

It’s not just that culture war issues and traditional non-economic issues focus on different topics. Culture war debates are relatively new, and that means people’s views on them might not line up neatly with their beliefs on older issues. This may be especially true in the UK, where these newer issues have sometimes split politicians within the same party or where party leaders have tried to avoid taking clear positions. Because of this, many people may not have strong opinions on them at all yet. That’s very different from more traditional non-economic issues, like crime or immigration, where the parties have clearer positions and voters are more used to thinking about where they stand.

Culture War Polarisation?

In my study, I included a range of different policies, so that I could compare the effect of the culture war with traditional (economic and non-economic) issues.

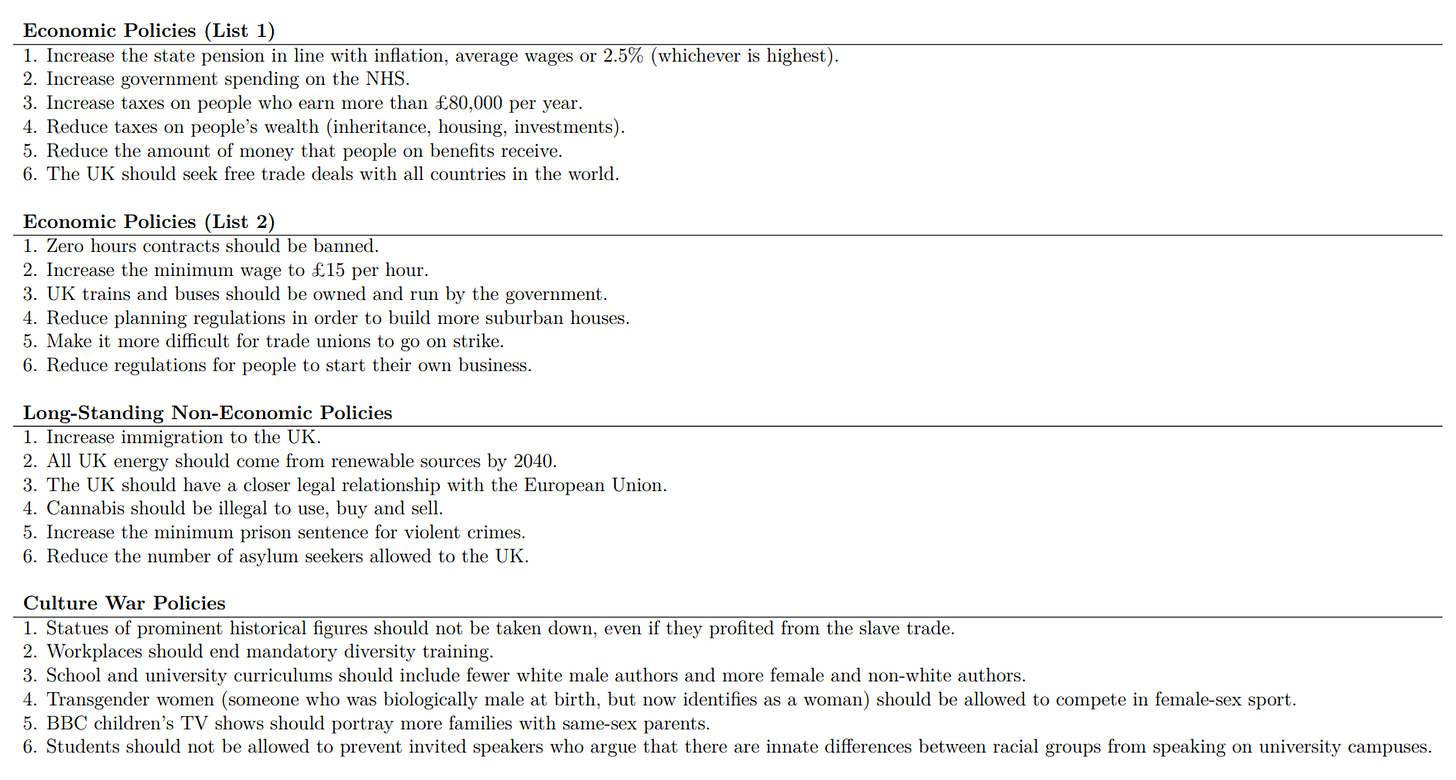

The culture war issues here are obviously not an exhaustive list of all possible ones, but they should cover the major topics that have been debated in the UK. Here are the agreement levels for the six I included.

Half of these are hardly what you’d call polarising. Agreement with getting rid of diversity training, diversifying the curriculum and more same-sex parent characters are all pretty evenly spread out. The most frequently option chosen was ‘neither agree nor disagree’, whilst the agreement and disagreement options were chosen at similar rates.

The policy against ‘cancel culture’ in universities is more skewed towards agreement, but not radically so. Again, the most frequently option chosen was ‘neither agree nor disagree’.

Keeping up statues is different. Most people lean in the same direction where ‘strongly agree’ is the most common response, followed by ‘agree’. While there are people who disagree, again, I wouldn’t say this is an example of polarisation. True polarisation would mean lots saying ‘strongly agree’ and lots saying ‘strongly disagree’ with few people in the middle. However, in this case, one side clearly dominates.

A policy in favour of transgender athletes is an even starker example of this. This was an extremely unpopular policy, with ‘strongly disagree’ being chosen by the majority of respondents.

However, popularity alone doesn’t tell us much. Just because a policy is widely supported or opposed doesn’t mean it actually matters to voters when they make decisions. The real test of how important culture war issues are is whether people are willing to overlook other policies they care about (like taxes or the NHS) in order to vote in line with their views on cultural issues.

Ace of Based

To test the relative importance of culture war issues, I ran a vote choice conjoint experiment in May 2023. A conjoint experiment is a type of survey designed to see how people make trade-offs between different policies. Rather than asking how much someone likes a single policy on its own, it asks them to choose between two imaginary candidates, each offering a mix of different positions. This helps reveal which issues actually influence people’s choices when they have to weigh them against other policies.

I worded this as a leadership contest within a respondent’s preferred party. Each respondent was presented with two candidates, each with a randomly generated four-policy platform. Each candidate supported two economic policies, one traditional non-economic policy and one culture war issue.

In my analysis, I focus on something called marginal means. This measures the proportion of people who chose a candidate supporting a particular policy. A score of 1 means everyone voted for the candidate with that policy, while a score of 0 means no one did. More realistically, anything above 0.5 means it was mostly voted for, while anything below 0.5 means it was mostly voted against.

Agree to Disagree

First, I looked at how people’s voting choices changed depending on whether they agreed or disagreed with a policy. For example, if people who agreed with Policy X had a marginal mean of 0.62, that means 62% of them chose the candidate who supported that policy.

The culture war consistently motivated more conservative respondents (those agreeing with conservative and disagreeing with progressive culture war positions) but had inconsistent effects on progressives (those agreeing with progressive and disagreeing with conservative culture war positions).

Conservative respondents significantly voted against all progressive policies and significantly voted for all conservative policies. This means that culture war issues strongly influenced how they voted.

For progressives, the pattern was less consistent. Some progressive positions (like supporting trans women athletes, opposing slave-trade statues, and disagreeing with anti-cancel culture) had no significant effect on vote choice. In other words, even though they agreed with progressive stances, it didn’t sway their vote compared with other issues.

While the other progressive policies did have a significant effect, the overall picture is still asymmetrical: conservative voters were more consistently influenced by these issues than progressive voters.

The above shows the policies with the highest marginal means depending on agreement with the policy. There isn’t really a trend in which issue group most motivates voters.

Of the top five highest, two are economic policies, two are culture war policies, and one is a traditional non-economic policy. Economic and traditional policies still effectively move votes, but voters also incorporate culture war beliefs. This is not to say the culture war is the most important issue group, but they can play a key role for voters.

The above shows the policies with the lowest marginal means. This gives a note of caution, because, of the five policies with the lowest marginal means, none are culture war issues.

Cross-Pressured Voters

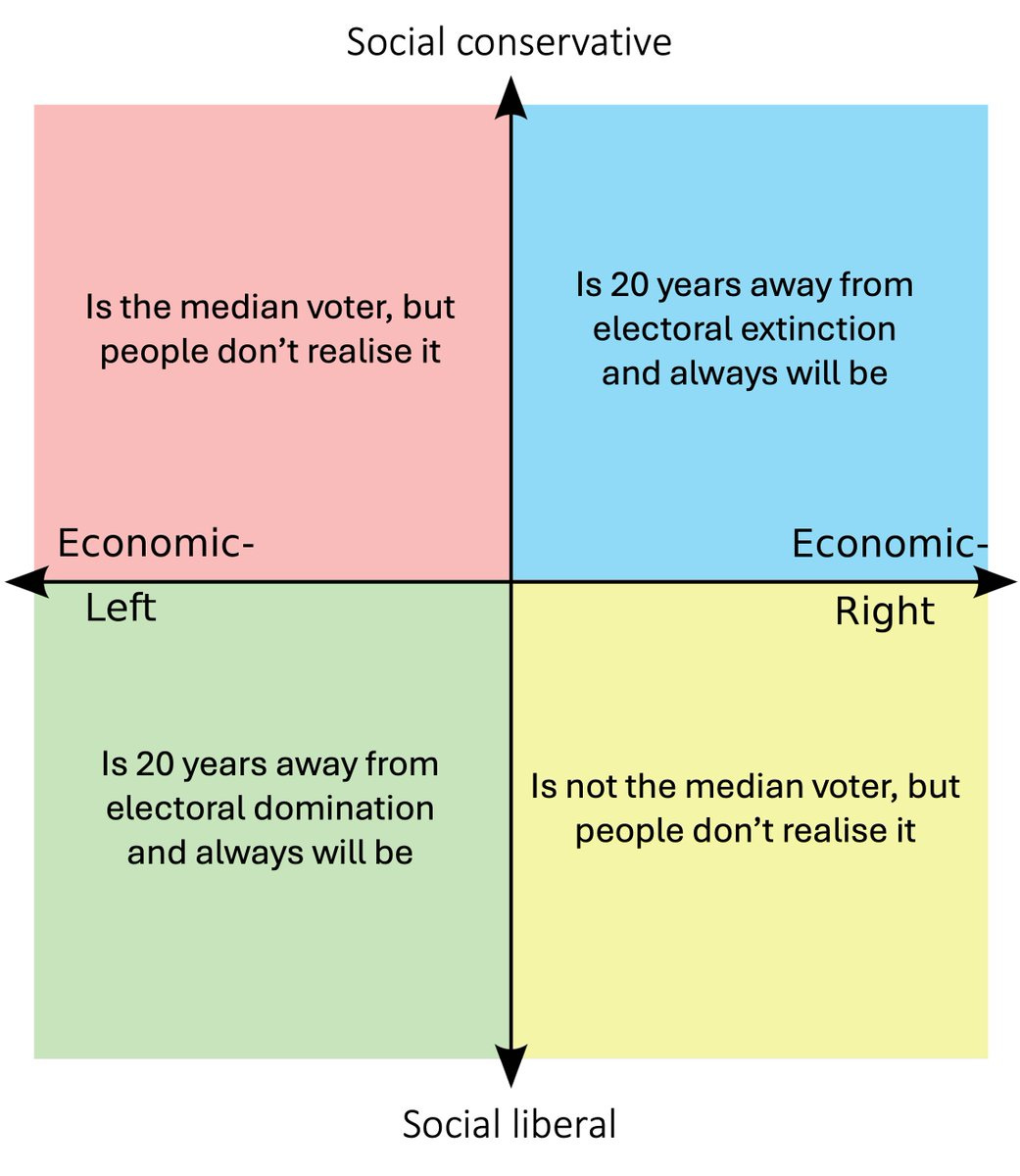

Sometimes voters are ‘cross-pressured’ where they agree with Party A’s economic platform but Party B’s non-economic platform. There are a lot of theoretical reasons (read the academic version if you’re interested) to believe that cross-pressured voters may prioritise the culture war over their economic beliefs. This is particularly relevant for voters with left-wing economic and socially conservative beliefs who are said to have been so crucial for the success of right-wing populism since 2016.

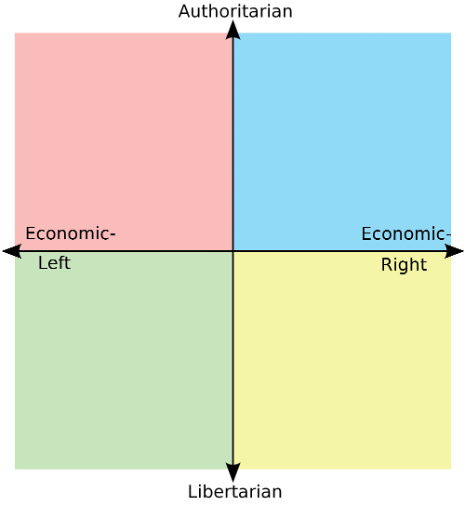

I used the left-right economic scale and the libertarian-authoritarian7 social scale included in the British Election Study, which have been shown to be good estimations of preferences on the economic and non-economic dimensions in the UK. These help us understand a person’s underlying political values, which are often more stable than their party preference.

In general, people tend to vote for candidates who share their political values, suggesting that the value-based questions used here capture real underlying traits.

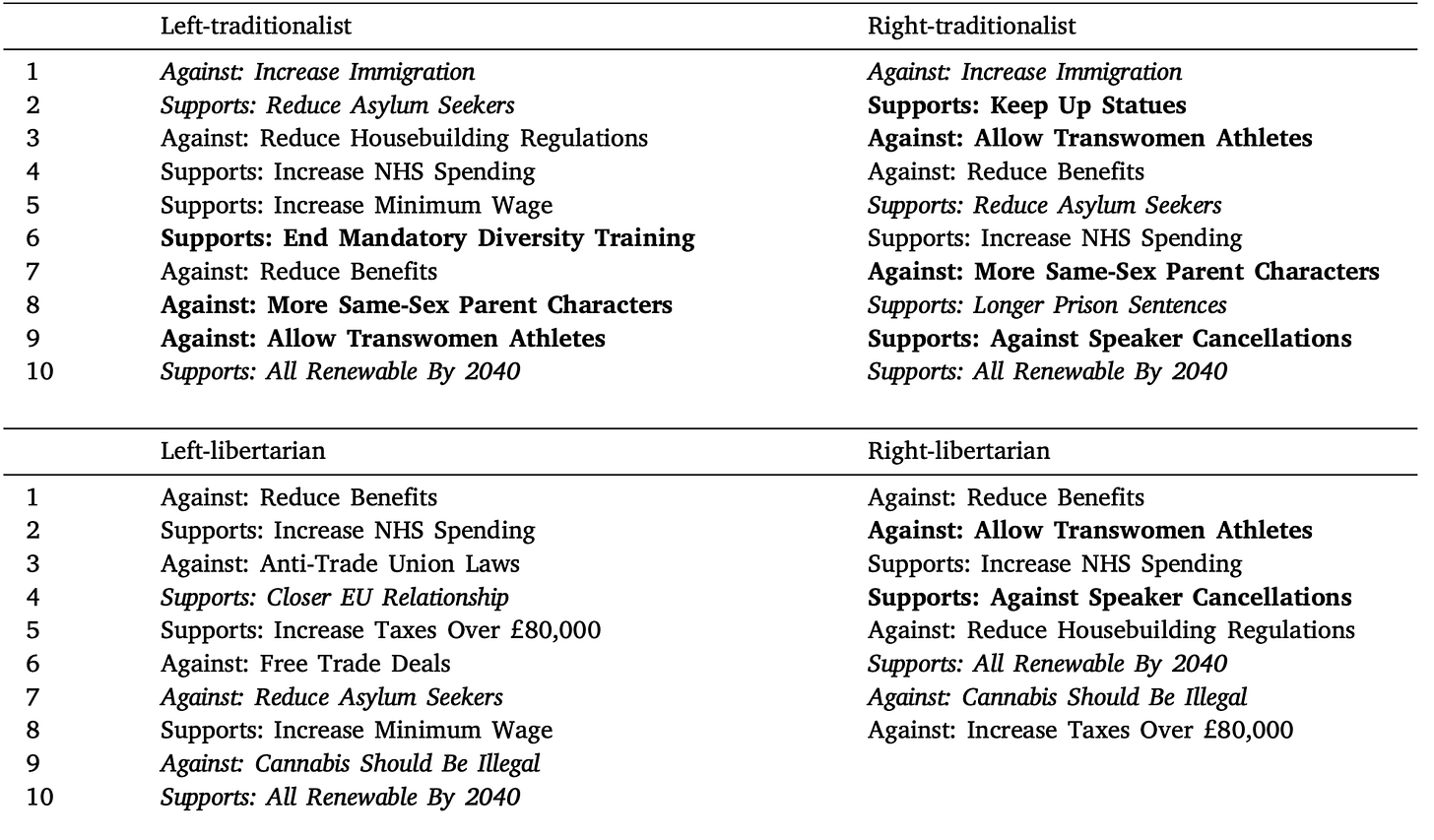

To understand how important the culture war is compared to other issues, I looked at the ten policies that were furthest from 0.5 for each value group. These are the issues that most strongly influenced vote choice and serve as a rough indicator of what each group prioritised.

For left-libertarians, none of their top ten issues were culture war. Instead, they were most motivated by economic policies (six out of ten) and traditional non-economic issues (four out of ten).

This contrasts with right-traditionalists who clearly prioritise the culture war. Although being against immigration was their top issue, four culture war policies are in their top ten, and two of these (keeping up statues and allowing trans women athletes) are in their top three.

Left-traditionalists, who are cross-pressured between left-wing economics and socially conservative values, showed a mix of both worlds. Culture war issues did matter to them, but much less so than for right-traditionalists. Three of the six culture war policies made it into their top ten, but only at sixth, eighth, and ninth place.

Instead, the issues that most motivated left-traditionalists were opposing increased immigration and supporting reduced asylum seekers.

They also aligned with left-libertarians on key economic positions, such as increasing NHS spending, raising the minimum wage and opposing benefit cuts. However, in their hierarchy of priorities, left-traditionalists cared more that a candidate had socially conservative policies on immigration and asylum.

(And, because I have a death wish, I should also mention that all groups, including left-libertarians, significantly voted against allowing trans women athletes.)

Another Another Way To Be Right

Socially conservative voters consistently placed greater emphasis on non-economic issues (both culture war and traditional) than those with socially liberal values. This supports Noam Gidron’s idea that there are ‘many ways to be right’ where it’s enough to be conservative on just one dimension for someone to vote for a right-wing party.8

For the political right, this highlights the strategic potential of non-economic issues in building a majority coalition. A lot of commentary around Reform UK suggests that their rise is fragile, because their voters span a wide range of economic views from Thatcherites to old left socialists. However, my findings suggest this might be the wrong way to think about it.

Right-traditionalists and left-traditionalists may disagree on economic policy, but that only matters if economics is what’s driving their vote. Instead, they both prioritised the non-economic concerns that they share.

In other words, economic disagreement within a voter coalition is not a fatal flaw if the economy isn’t what’s motivating their political decisions. If voters aren’t using economic policy as a litmus test, then their differing views on it may not pose a serious risk to party unity. By focusing on the non-economic values their supporters share, they can hold together an ideologically diverse coalition that might otherwise seem impossible to reconcile.

As with my previous Substack post, the key point is that what really matters is how much someone cares about an issue, not just what they think about it. Just because someone agrees with a policy doesn’t mean it will influence their vote. Sometimes an issue will attract them to a party, but other issues will have no effect.

This is where traditional polling often falls short. It tends to assume that agreement equals support and disagreement equals opposition. But public opinion isn’t that one-dimensional. A popular policy isn’t necessarily a vote-winner, because if people don’t care about it, it won’t move the dial.

That’s why it’s important to distinguish between culture war issues that genuinely resonate with the public and those that people don’t care about. Some issues consistently showed broad, cross-cutting appeal/repudiation, but others had little to no impact in the experiment.

This distinction is crucial for right-wing politicians. An obsessive focus on issues that don’t resonate with the public (while ignoring the economic or non-economic issues that genuinely shift votes) signals that you are more interested in feeding the media cycle rather than responding to what voters actually care about. A mismatch between the public’s cultural values and the cultural values of political / media / academic / NGO / QUANGO elites creates major political opportunities for the right, but also creates major opportunities for diversion.

Leaving the Left-Wing Left Behind

For the left, though, this shows the difficulty in forming winning voter coalitions around economic issues when non-economic policies are prominent. There are (at minimum) five options available to the left to deal with this, all of which involve risk.

First, support and champion ‘woke’ and other socially liberal policies.

Best case: new culture war issues become standard left-right divides because your own voters start supporting them due to partisanship. You unite all socially liberal voters, including right-libertarians. You are also able to keep the left-traditionalists who prioritise their economic beliefs.

Worst case: your support for unpopular new culture war issues doesn’t mean left-traditionalists change their views, but, instead, they change their party away from you. Right-libertarians prioritise their economic preferences and keep voting for the right. At the same time, you raise the salience of cultural matters but are seen as insufficiently liberal for many left-libertarians who vote Green or Lib Dem rather than your ‘diet coke’ version.

Second, ignore the culture war and hope it goes away.

Best case: by not engaging, non-economic issues stay low salience and you maintain a broad coalition by keeping things vague. You are therefore able to move the conversation on to economic issues where the left is the majority.

Worst case: like that strange lump on the side of your neck, it doesn’t go away if you ignore it. Your opponents define you on these issues anyway and you’re left looking weak or evasive on something the public increasingly cares about.

Third, go anti-woke.

Best case: you align with majority opinion, avoid alienating swing voters and solidify left-traditionalist support. You keep left-libertarians who prioritise the economy, as well as winning some right-traditionalists who like the cut of your jib.

Worst case: you lose on both sides. Left-libertarians abandon you, going on long Bluesky rants about how you are the reincarnation of Enoch Powell. At the same time, left-traditionalist voters who dislike ‘woke’ politics don’t trust your conversion which comes across as fake and opportunistic.

Fourth, wait for an anti-woke politician to win office and hope they mess up the economy.

Best case: economic failure makes the government unpopular and discredits their anti-woke agenda by association. People stop caring about the culture war and swing back to bread-and-butter issues and the value of competence.

Worst case: voters still like anti-wokeness and, when the economy tanks, the government goes in even more on culture war stuff because it’s all they have left. If the economy recovers, you’re still stuck where you started: unpopular on the issues people are now most focused on.

Fifth, win office yourself and run the economy well.

Best case: your government’s economic success earns broad public approval. A strong economy shifts focus away from divisive cultural issues, whilst the resulting sense of stability makes voters more open to socially liberal changes. You build support across the political spectrum by delivering on what matters most to people day-to-day.

Worst case: a well-functioning economy creates the conditions for culture wars to flourish. With material concerns under control, people turn their attention to identity, values and social issues. These ‘post-material’ concerns rise in salience, and since the majority of the public still leans socially conservative, the right reaps the electoral rewards.

I don’t know which of these is best. But it’s probably best to pick one and stick to it, rather than trolley back and forth depending on the news cycle.

Why Did The Right Care More About the Culture War?

I don’t know.

All that my data shows is that socially conservative voters tended to care more about the culture war when making voting decisions. It doesn’t explain why. However, there are several plausible reasons why this was the case.

The psychology of loss

Behavioural psychology is clear that people tend to feel losses more intensely than gains.9 In recent decades, progressive values have made real advances on race, gender, sexuality, and identity. For conservatives, this means they actually have lost out. This means their pain of loss is stronger than progressives’ happiness for their gains, therefore motivating conservatives’ vote more.

(This also raises the question of, if liberal cultural gains are reversed, whether progressives will begin to prioritise the culture war more.)

This links to what political scientists have called ‘cultural backlash’ to progressive social change.10 Since 2016, we’ve seen growing support for right-wing populism from working-class, ethnically majority voters, even if they often hold left-wing economic views.

For many of these voters (what I called left-traditionalists) voting with the culture war can feel like a way to push back against declining social status in diversifying societies. It’s not just about policy, but about identity, dignity and visibility.

Feeling Culturally Out of Place

Relatedly, people who work in universities, the media, the arts and the other cultural institutions where the culture war takes place tend to be much, much, much more socially liberal than the general public.11 This creates a gap both in values and representation between these institutions and voters.

If socially conservative voters look at the kinds of ideas being championed in schools, museums, films, TV shows or universities, it is not irrational for them to feel like these places do not reflect their beliefs or way of life. The sense that one’s values are routinely sidelined or dismissed can generate frustration and resentment.

When a politician comes along promising to challenge or rein in these institutions, voting for them can offer more than just policy alignment. It can also feel like a way to assert your values and to strike back at institutions that seem to look down on what you believe in.

Elite and media cues

Another potential factor was that right-wing politicians and media had spent a lot of time talking about culture war issues before my survey. We know from political science that people often take cues from elites and this could help explain why conservative voters may have prioritised cultural issues.

This shouldn’t necessarily be seen as a nefarious plot or manipulation. Politicians have always strategically emphasised issues that energise their supporters, divide their opponents and build coalitions. If cultural issues help do this, then foregrounding them is simply effective political communication.

Critics often argue that politicians ‘artificially’ inflate the importance of the culture war by constantly talking about it. That’s true, but the same is true of any political messaging. If Labour campaigns heavily on the NHS, they’re also elevating its salience, even if voters weren’t thinking about it before. That’s how agenda-setting works. All parties highlight the issues where they feel strongest and most united. The culture war is just one more example of that dynamic in action.

The same logic applies to commercial media who are incentivised to focus on content that draws attention. Culture war stories are often emotionally charged, identity-focused and polarising, which is exactly the kind of content that generates clicks, shares and engagement. If news organisations find that culture war topics consistently perform well, they’ll naturally cover more of them.

Conservative Party Trying Nothing and Being All Out Of Ideas

‘Elite cues’ are one thing, but one of the defining features of the last Conservative government was their complaints about ‘wokeness’. They repeatedly warned that progressive ideology had become deeply embedded in the civil service, BBC, universities, charities and other institutions of British life.

But the obvious problem with that is that they were in government the entire time. If wokeness in state institutions was such a grave threat, why didn’t they do anything about it? Why did they let it begin, grow and take hold under their watch? They were either a negligent party or a stupid party.

Throughout this period, they talked as if they were the opposition, while doing little – if anything – to address the issues they identified.

Conservatives: ‘Wokeness is a big problem and needs to be stopped.’

Voters: ‘Ok, what are you doing about it?’

Conservatives: ‘We’re complaining about it.’

Voters: ‘But you’re the government. Why aren’t you actually doing something?’

Conservatives: 🤷

It therefore wouldn’t be a surprise if that gap between rhetoric and delivery would breed cynicism and frustration from right-leaning voters. When people like this were presented with a candidate who promised to take real action in the conjoint experiment, they jumped at the chance to support them. Faced with years of Conservative hand-wringing and inaction, many were looking for someone who didn’t just share their concerns, but was actually willing to do something about them.

Say what you like about Trump/Vance, but they are at least logically consistent. They identified what they saw as a problem (progressive overreach in public institutions) and are now using/extending government power to try to change those institutions. You might oppose their agenda, but their approach at least makes sense.

Top-Down or Bottom-Up?

This all raises an important but unresolved question: is public interest in the culture war primarily top-down, shaped by elite messaging and media emphasis? Or is it bottom-up, driven by popular engagement with these issues? The truth is likely some mix of both, but the direction of influence isn’t always easy to untangle.

Politicians and the media have routinely committed ‘attempted culture war’, but not all of the issues they raise have succeeded in capturing public attention. Some issues resonate with the public and dominate political debate, but others have no effect with barely a ripple.

What makes certain topics ‘stick’ while others fade quickly? That question cuts to the heart of the top-down vs bottom-up debate.

Yes, politicians and media can try to elevate issues, but cultural flashpoints don’t gain traction just because elites push them. They stick when they tap into something within people. In that sense, elite messaging may light the match, but it’s the public that decides whether there’s enough dry kindling for a fire.

The Vibes They Are a-Shiftin'

Cultural conflicts are not static and new issues will inevitably emerge. The issues tested in my research were relevant at the time of study, but future cultural flashpoints will take on different forms.

Keeping in mind that the culture war is ever evolving can prevent mistakes of the past. Changing public opinion on topics that were prominent in the latter half of the 20th century led to some pronouncing that the culture war had ended. For example, in the US, Ruy Teixeira argued in 2009 that the cohort replacement (i.e. death) of socially conservative, non-college educated white people with socially liberal, multi-ethnic, college-graduate Millennials . . .

. . . is good news for progressives, both because tolerance and equal rights will increasingly be the ethos of the country and because progressives will increasingly be able to make their case on critical policy issues without significant interference from ‘hot button’ social issues promoted by conservatives.

😂😂😂

To be fair, Teixeira has since rescinded this view in light of events (this doesn’t happen very often, so should be applauded and celebrated whenever it happens).

And also to be fair to Teixeira, he wasn’t completely wrong. By ‘hot button’ issues, he was referring to things like gay marriage and abortion. Support for gay marriage is now high across the US. Although American conservatives were able to overturn Roe v. Wade in 2022, this was done through the courts. When abortion has been put to voters in referendums, the pro-choice positions have won the vast majority of the time even in more conservative-leaning states.

What this line of argument ignores is that the specific topics of the culture war change. Trump campaign heavily on new issues such as opposition to trans women’s participation in female-sex sport and the proliferation of D.E.I. departments, neither of which were – or could have even been imagined as being – electoral topics until recently.

What particularly discombobulated the ‘emerging Democratic majority’ view of cohort replacement was that Trump gained notable increased support from the young and racial minorities, both of whom were previously assumed to be put off by conservative culture war stances.

Cohort replacement may well make some older culture war issues decline, but it is a mistake to think that these will not be replaced by new ones.

The changing nature and persistent vote-winning potential of the culture war also raises questions about the nature of social conservatism more broadly. There is a tendency from some to assume and argue (like Teixeira used to) that cohort replacement will soon render right-wing parties and/or socially conservative politics an electoral irrelevance.

However, the fluid and shape-shifting nature of the culture war challenges this. Rather than being tied to a specific set of issues, social conservatism may instead be flexible in content and can become attached to a wide range of issues. If a new issue emerges that is an attempt to upend social norms that people either took for granted or held dear, then resistance to this means it can be absorbed into the broader category of social conservatism.

Although younger people may be more liberal on previously hot-button issues, they are not immune to worries about social change or cultural instability. When new issues trigger these concerns, diverse voters can still be drawn to parties that speak to them.

Cultural attitudes should be better thought of as a relative spectrum, rather than an absolute one, where what is deemed ‘conservative’ or ‘liberal’ changes over time.

Think about someone born in 1940. At age 20 in 1960, if they believed that homosexuality should be legal (but not adoption or marriage etc.) they would still have been considered socially liberal. If, in 2025 at age 85, they still believed this, they would now be considered socially conservative, even though their opinions haven’t changed.

The boundary of what counts as ‘socially conservative’ is constantly being redrawn, with today’s conservatism either reflecting a version of what was considered liberal in previous decades or representing entirely new issues that have only recently become politically divisive.

One of the defining features of the transgender division in the UK is that some of the most high-profile ‘gender critical’ campaigners are women who were considered very liberal in the pre-woke era.

The enduring appeal of ‘social conservatism’ is particularly significant in light of ageing populations. Research on age effects suggests that individuals become more conservative (in the sense of valuing stability and tradition more) as they get older.12 This matters for elections because older people are more likely to vote and are a growing proportion of the electorate. If social conservatism is indeed flexible in content, then rather than declining, it may instead become a more potent electoral force going forward, because older people will have an increasingly outsized effect on electoral outcomes.

The crucial point, however, is that the substance of what qualifies as ‘socially conservative’ will be very different to today.

“This Is Not a Peace. It Is an Armistice for Twenty Years”

So (possibly) said Ferdinand Foch, the French general and Supreme Allied Commander about the Treaty of Versailles. He saw it not as a lasting peace, but as a temporary pause before the next inevitable conflict.

If it is not too inappropriate (it is), you could say the same thing about the culture war. Its salience rises and falls, but it never truly disappears. Post-WWII history shows that the culture war comes in waves. It fades, regroups and then re-emerges under new names and with new symbols.

In the late 1960s, the counterculture/hippies rejected ‘mainstream American values’, pushed for free love, and challenged established norms in ways that had never been seen before. On the other side stood the ‘silent majority’ of those who felt alienated by the rapid social changes and rallied around traditional values, law and order and patriotism. This division seeped into pop culture, politics and media, shaping a new kind of ideological battlefield.

By the 1970s, the culture war began to wind down. The Vietnam War ended, major protests subsided, and many former radicals (like Jerry Rubin) traded in activism for suits and stock options, ushering in the yuppie era of ambition and material success.

But by the late 1980s, a new phase began. The term ‘political correctness’ entered public discourse. University campuses became the stage for new battles over language, identity and inclusion. The ideas brewing in academia started spilling over into the broader culture. Sound familiar?

The 1994 cult film PCU satirised this moment, portraying a campus where every word could spark outrage.

Then came another quiet spell. The late 1990s were marked by economic and geopolitical optimism. Some even saw the election of Barack Obama in 2008 as the beginning of a ‘post-racial’ America.

Around 2015, the next wave hit. Black Lives Matter, Me Too, debates over gender identity, pronouns, safe spaces, statues, and free speech. Topics that once felt niche became central. Culture war debates migrated from universities to workplaces, boardrooms, social media and parliaments. For a time, they were impossible to avoid.

Then, again, a shift. By 2022, as inflation soared, Russia invaded Ukraine and living costs spiralled, public attention began to pivot back to material concerns. Cultural flashpoints still existed, but they no longer dominated headlines in the same way. Ideas and aesthetics that would have felt shockingly subversive just a few years earlier now seemed like anachronistic period-pieces from a different era.

This isn’t the end, it’s just a pause. If past cycles hold, the culture war will return for a new generation in around 2045 or so. It will feel different, but it will rhyme with the past. The battles may evolve, but the terrain (identity, values, belonging) will stay the same.

Pippa Norris. “Mobilising the Womens’ Vote: The Gender-Generation Gap in Voting Behaviour.” Parliamentary Affairs 49/2 (1996)

Herbert Kitschelt. The Transformation of European Social Democracy. Cambridge University Press, 1994.

Yes, I know these things have economic components to them, but the research in academia is that they tap into different values to a person’s economic left-right beliefs.

Steve Bruce. Sectarianism in Scotland. Edinburgh University Press, 2019.

Keith Daniel Roberts. Liverpool Sectarianism: The Rise and Demise. Oxford University Press, 2017.

When I describe issues as ‘culture war’ it is not intended to trivialise or disparage them but is used neutrally to denote issues which are qualitatively different from economic or longer-standing non-economic issues in politics.

In academia, the terms that are used are ‘Libertarian’ and ‘Authoritarian.’ Using the term libertarian is confusing because in popular political conversation it means someone who is both economically right-wing and socially liberal, whereas in academia it means someone who is socially liberal regardless of their economic opinion.

Using the term authoritarian to describe social conservatism is also inappropriate. Authoritarianism is (and as a term should only be used to describe) a non-democratic government regime and people who have anti-democratic beliefs. Some people who are socially conservative support dictatorships, sure, but the overwhelming majority in the UK don’t – and, obviously, not all anti-democratic regimes have been right-wing.

It says a lot about academics that they will happily and unthinkingly use – without recognising or acknowledging the immense amount of political bias this displays – the same term for Mussolini that they do for someone who thinks immigration is too high.

Noam Gidron. “Many ways to be right: Cross-pressured voters in Western Europe.” British Journal of Political Science 52/1 (2022): 146-161.

Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. “Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk.” Econometrica 47/2 (1979): 363-391.

Pippa Norris and Ronald Inglehart. Cultural backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism. Cambridge University Press, 2019.

Daniel Oesch. “The changing shape of class voting: An individual-level analysis of party support in Britain, Germany and Switzerland”. European Societies 10/3 (2008): 329-355.

Daniel Oesch and Line Rennwald. “Electoral Competition in Europe's New Tripolar Political Space: Class Voting for the Left, Centre‐right and Radical Right.” European Journal of Political Research 57/4 (2018): 783-807.

Glenn Wilson. The Psychology of Conservatism. Routledge, 2013.

Let’s rewrite what they forgot:

Wealth is who you hold.

Profit is peace you sold.

Legacy is love untold.

https://thehiddenclinic.substack.com/p/the-lost-ledger

Yeah

They don’t