What Do The Public Actually Think About Economic Growth, Technological Change and "Abundance"?

There's an "anti-growth coalition" and a “pro-growth coalition” out there, it’s just not necessarily the people you think it is

Hello there! 😀

During her time as prime minister, Liz Truss criticised what she called the “anti-growth coalition.” This was a group of politicians, activists and commentators who she claimed were standing in the way of Britain’s economic success.

Although Truss argued that this was made up of people and groups the British right-wing have long had a negative view of, the idea there are forces actively working against economic growth has gained support across the political spectrum.

One of Rachel Reeves’ first actions as Chancellor was to unveil plans for a “new era for economic growth” and Keir Starmer has outlined how securing “the highest sustained growth in the G7” is a key “national mission” in power. Starmer also defined his own version of the anti-growth coalition, saying that his government would favour “the builders not the blockers.”

However, as far as I can tell, no one has yet tried to design survey questions that systematically measure how people actually feel about economic growth itself. That’s a big gap, because it seems like there might be both a “pro-growth” and an “anti-growth” coalition within public opinion, but that these won’t line up neatly with the usual left-right divides.

To test this, I ran a poll with Focaldata of 1,002 British respondents over 28-30 August 2024 with a series of questions to better understand the full spectrum of people’s beliefs. What emerges is that there really are both anti-growth and pro-growth groups out there.

What’s more surprising is how these groups are made up. Growth turns out to unite people who are usually on opposite sides of politics and to divide people who are normally allies. It also splits people by class, but not in the old working-class versus middle-class way. The divide runs along lines of who’s benefited from change and who’s been left behind.

An earlier version of this article was published on Focaldata’s blog under the title “Is there an anti-growth coalition in Britain?” and can be accessed here: https://www.focaldata.com/blog/bi-focal-20-is-there-an-anti-growth-coalition-in-britain

Possible Growth Coalitions

On the right, libertarian thinkers see capitalist growth as the foundation of prosperity and progress. They argue that the free-market provided the freedom to innovate, trade and create which then lifted millions out of poverty.1 On the left, equitable growth is similarly defended for its social benefits, where expanding the economy creates the resources needed to improve living standards and fund public services.2

At the same time, both sides have critics of growth. Some conservatives believe the pursuit of growth destabilises or undermines traditional community, culture and national identity.3 Indeed, Hayek named this “fear of change [and] a timid distrust of the new” as the reason he was not a conservative, because he instead favoured letting “change run its course even if we cannot predict where it will lead” (pages 521-522).4

Many on the left, meanwhile, see growth as the root of exploitation and inequality.5 Others question whether economic expansion actually makes people happier, arguing that beyond a certain point, more wealth doesn’t mean more wellbeing.6

Housing

Housing is a specific example of how attitudes to growth cut across party lines. In the United States, parts of the left have recently embraced what they call “supply-side progressivism” or a “liberalism that builds” in order to promote an “abundance agenda.” Their core argument is that well-intentioned building regulations are now being used to block the things society needs, such as new homes, transport and energy projects.7

The free-market right have made essentially the same points that a slow and bureaucratic planning system has created resentment and made it too hard to get things built. These restrictions, they say, are holding back growth and making life more expensive.8

At the same time, new construction has also been opposed across the spectrum. On the left, environmental concerns have led to resistance to increased infrastructure development.9 On the right, opposition often comes down to concerns it will change the character of the local community.10

Paving paradise and putting up a parking lot would be divisive. Joni Mitchell would be in the anti-growth coalition and Alan Partridge would be in the pro-growth one!

Environment

On the left, the “degrowth” movement argues that tackling climate change is incompatible with endless economic expansion.11 After Liz Truss’s comments, environmentalist George Monbiot proudly called himself part of the “anti-growth coalition,” arguing that what economists call progress is, in ecological terms, destruction.12

Some conservatives, like philosopher Roger Scruton, have made similar arguments. Scruton criticised the environmental damage caused by industrial growth and called for a renewed “green conservatism” focused on stewardship and conservation.13

Then there are those on the pro-growth side who reject this trade-off on left and right. They believe in “sustainable growth,” where innovation and clean energy can allow economies to grow while cutting emissions.14 They point to the evidence that developed countries have accomplished sharp drops in their per capita carbon dioxide emissions whilst growing GDP per capita.15

Technology

The rise of artificial intelligence and automation has sparked a new divide between those who see technology as a threat and those who see it as the key to a better future.

Pessimists worry that rapid advances in AI will lead to widespread job losses, social disruption and even existential risk.16 Optimists, on the other hand, argue that every major technological shift in history has created more opportunities than it destroyed. They believe AI and other innovations will solve old problems and improve lives across the board.17

Carry On Keir

Finally, Keir Starmer recently created an entirely new growth coalition. On 1st September this year, he announced the appointment of a Chief Secretary and Chief Economic Advisor with a press release that began:

Today the Prime Minister is bolstering the Downing Street operation as this government delivers on the country’s priorities: growth people feel in their pockets, secure borders, and getting the NHS back on its feet.

Ooh, Matron!

This could really be the stimulating package to perk the nation up. Perhaps a bit of pump-priming to get things flowing again? Or maybe the invisible hand helps create some upward mobility? One can only hope his new team know how to keep things steady if the figures start to rise.18

What Do People Think “Economic Growth” Is?

Enough Carry On jokes, let’s get to the data.

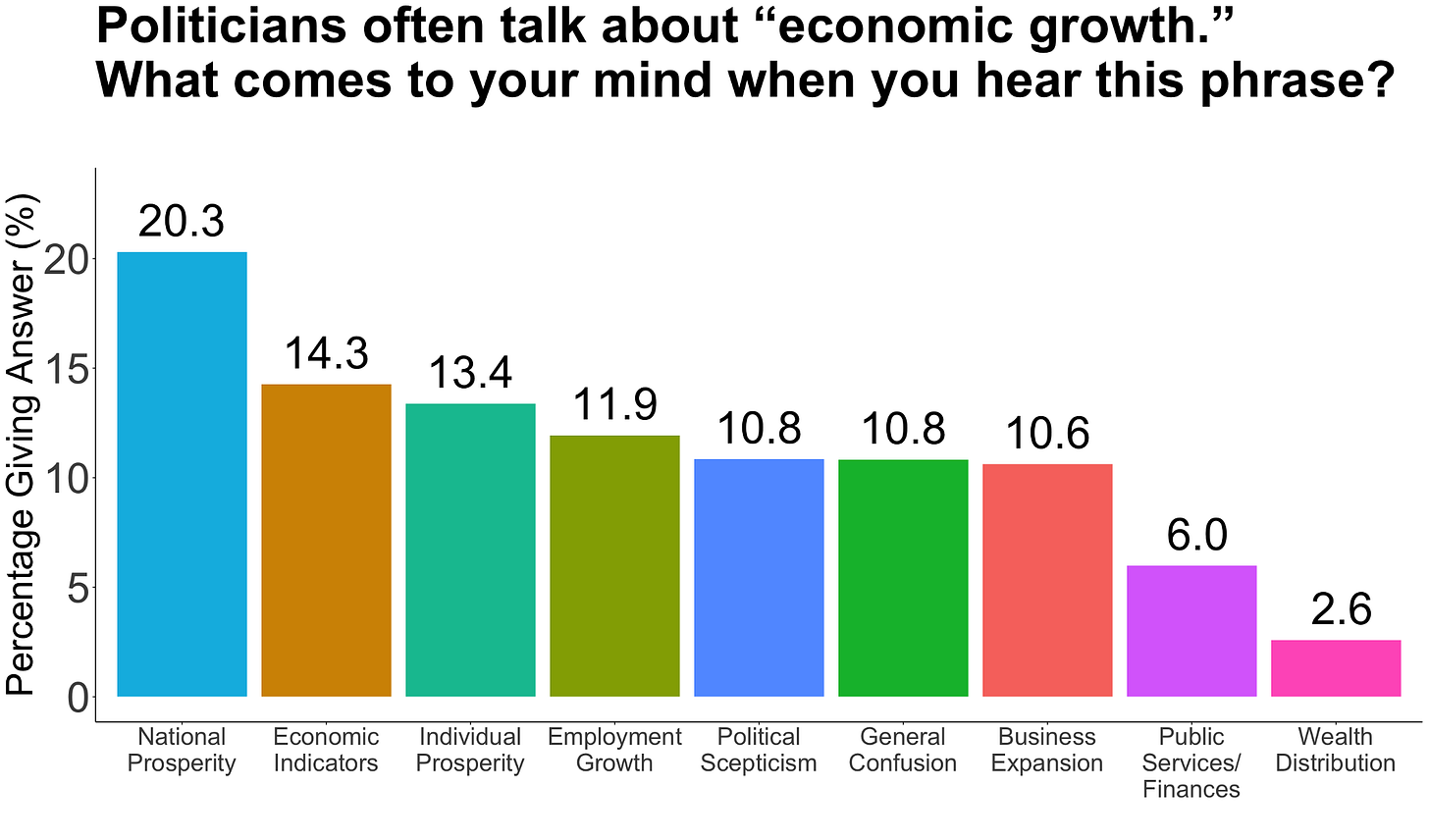

Politicians love to talk about “economic growth.” The problem is that political language often assumes two things that might not actually be true: first, that everyone understands what these words mean; second, that everyone shares the same definition.

When people hear “economic growth,” are they picturing GDP going up, more jobs being created and higher pay packets? Or are they cynical about politicians’ promises and sceptical about whether any growth will get seen by them?

First, we asked:

Politicians often talk about “economic growth”. What comes to your mind when you hear this phrase?

Respondents were given the chance to type whatever answer they wanted. Using natural language processing, we found that there were nine common topics raised.

There is a pretty wide spread of answers. The most frequent were people mentioning something to do with national prosperity, but without a specific indicator mentioned.

“That the economy is going on the right path.” – 34-year-old white woman, lives in South West England, 2024 Labour voter

“A more prosperous country” – 59-year-old white woman, lives in Scotland, 2024 SNP voter

“Getting stronger and better off” – 37-year-old white woman, lives in East Midlands, 2024 Labour voter

Over 14% of respondents were able to give a particular economic indicator, such as GDP, productivity or exports. Over 13% mentioned increased individual purchasing power or an improved cost of living.

This was different to the almost 12% of respondents who named increased employment specifically and the 10.6% who mentioned business expansion or higher company profits..

Notably, almost 11% of respondents gave an answer which indicated scepticism towards politicians and their claims about economic growth.

“Another meaningless political phrase” – 62-year-old white man, lives in South East England, 2024 Lib Dem voter

“I am fed up of listening this phrase from politicians because they are the destroyers” – 49-year-old Asian man, lives in West Midlands, 2024 Labour voter

“They may talk about growth but only serve to destroy the country’s economy” – 41-year-old white woman, lives in South East England, did not vote in 2024

There was also a high level of misunderstanding with almost 11% of respondents giving an answer that signalled that they weren’t sure what politicians meant when they said economic growth.

“I dont know as I dont pay attention to anything related to politics” – 36-year-old white woman, lives in West Midlands, did not vote in 2024

“I hear it talked about but am not certain what it actually means” – 70-year-old white woman, lives in Scotland, 2024 Conservative voter

“I have no idea about economics” – 49-year-old mixed-ethnicity man, lives in North West England, 2024 Labour voter

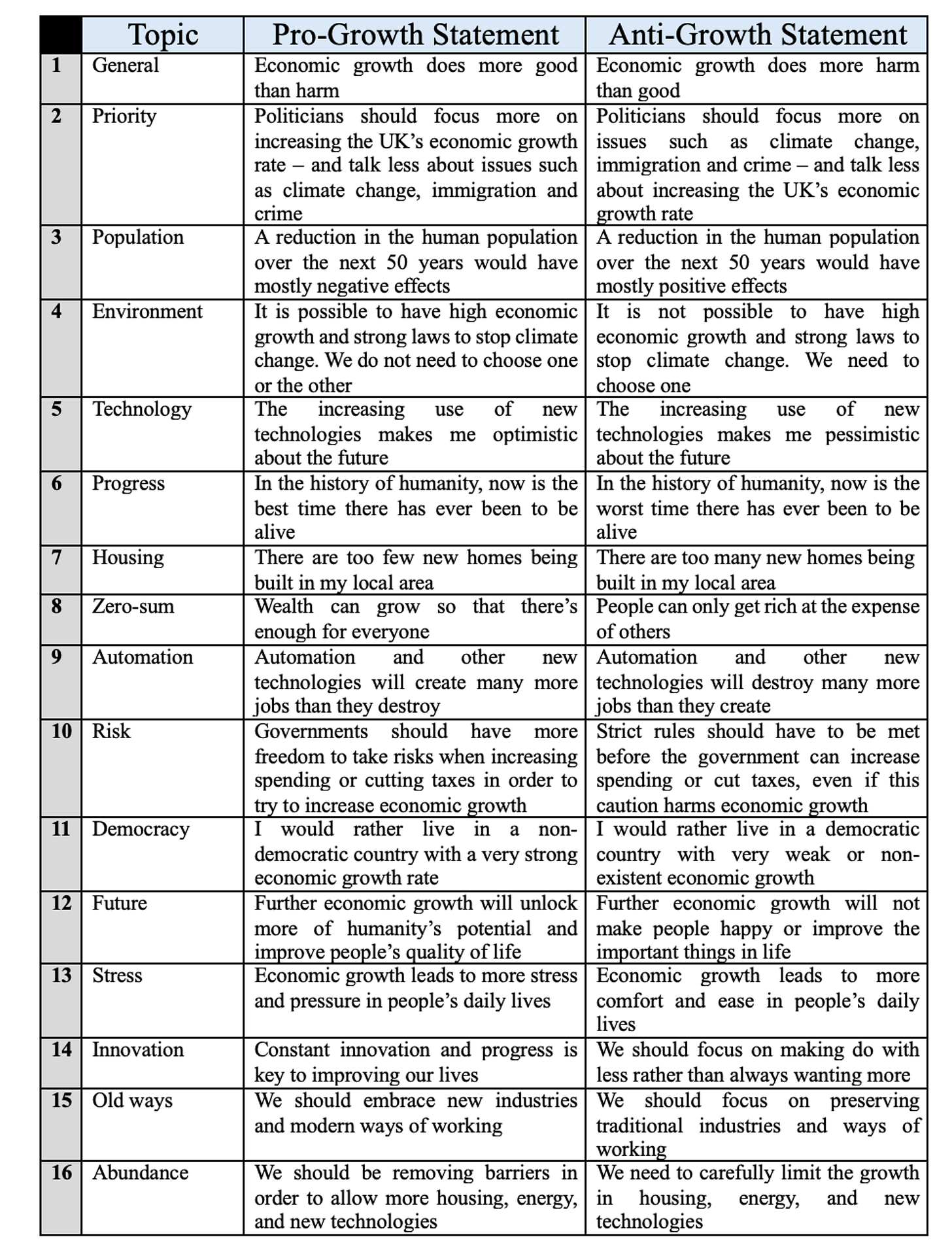

Dimensions of Growth

We then asked respondents to place their views between a series of two statements on a 0-10 scale, with one side being anti-growth and the other being its pro-growth opposite. These were created to cover the main debates.

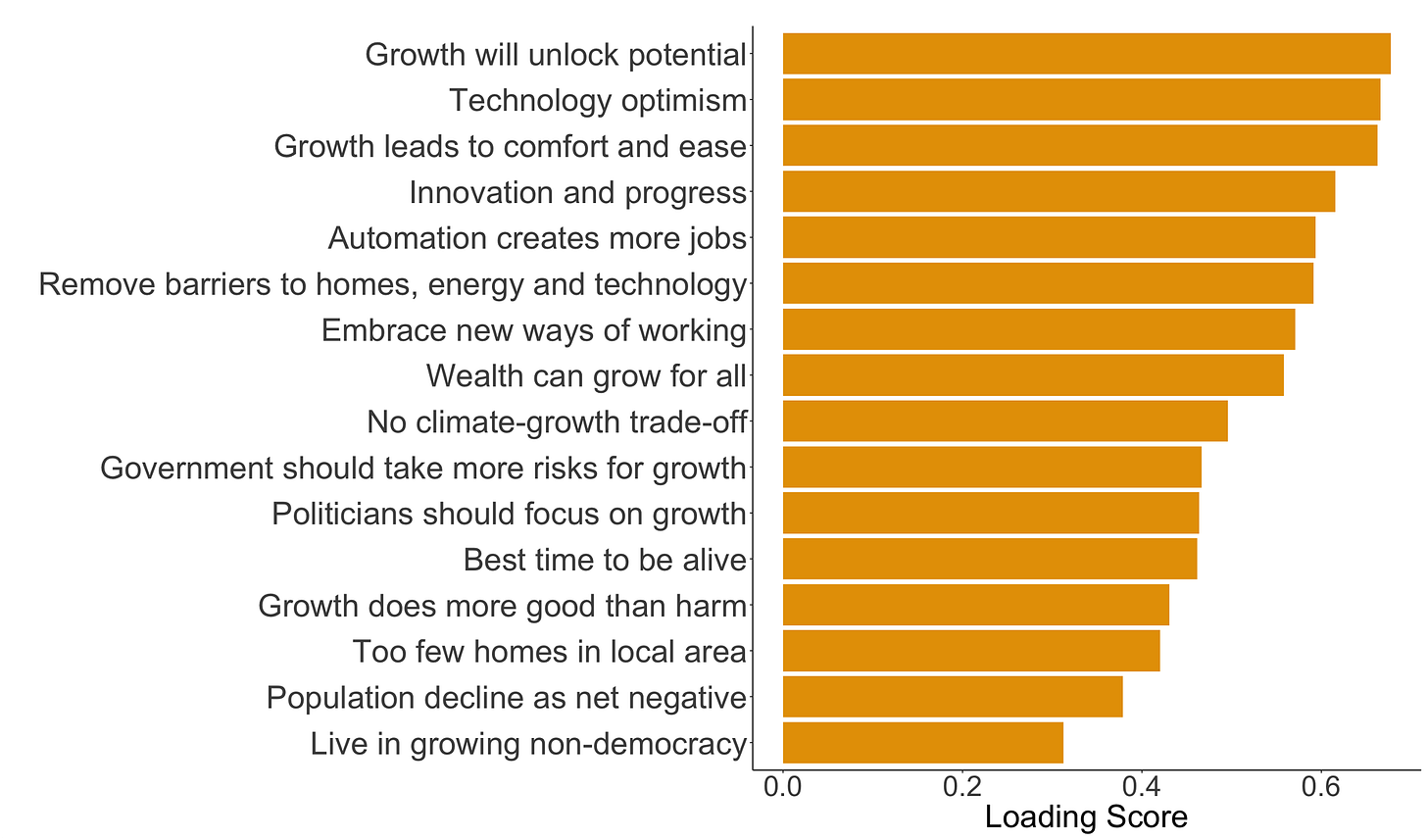

To make sense of how people answered, we used something called factor analysis. In simple terms, this is a method that looks for patterns in how people respond and tells us whether questions are really measuring the same underlying attitude.

All the statements loaded in the same direction, which means that people who agreed with one statement were also likely to agree with the others. People don’t just support/oppose one aspect of growth, they tend to support/oppose the rest too.

The statements that best captured this shared outlook each had a strong factor loading (above 0.5):

Further economic growth will unlock more of humanity’s potential and improve people’s quality of life

The increasing use of new technologies makes me optimistic about the future

Economic growth leads to more comfort and ease in people’s daily lives

Constant innovation and progress is key to improving our lives

Automation and other new technologies will create many more jobs than they destroy

We should be removing barriers in order to allow more housing, energy, and new technologies

We should embrace new industries and modern ways of working

Wealth can grow so that there’s enough for everyone

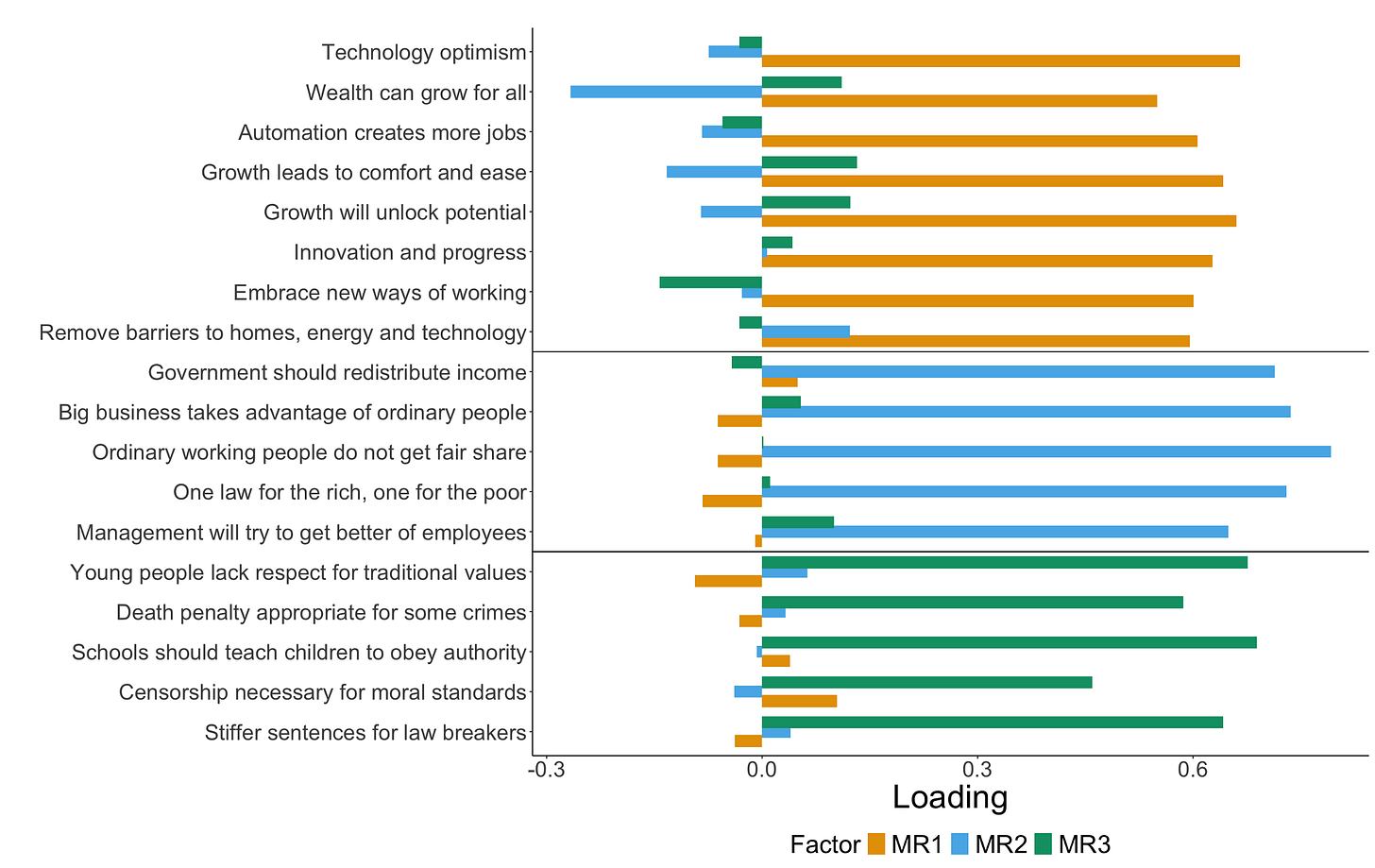

However, attitudes towards growth may just be another way of measuring traditional economic left-right values or cultural liberal-conservative values. To test this, we did another factor analysis, but this time these eight best growth statements were included alongside the economic and social/cultural values questions used in the British Election Study (BES).

The above shows that there are three clear and distinct dimensions of political beliefs. Each of the three factors is consistent within its own group of questions but clearly different from the others, as illustrated by the three coloured bars.

People’s beliefs on growth are almost always unrelated to their left-right economic or socially liberal-conservative beliefs. This suggests that views about the benefits/downsides of growth form both an internally coherent belief system but also that it’s a separate dimension of political thinking that cuts across the usual boundaries.

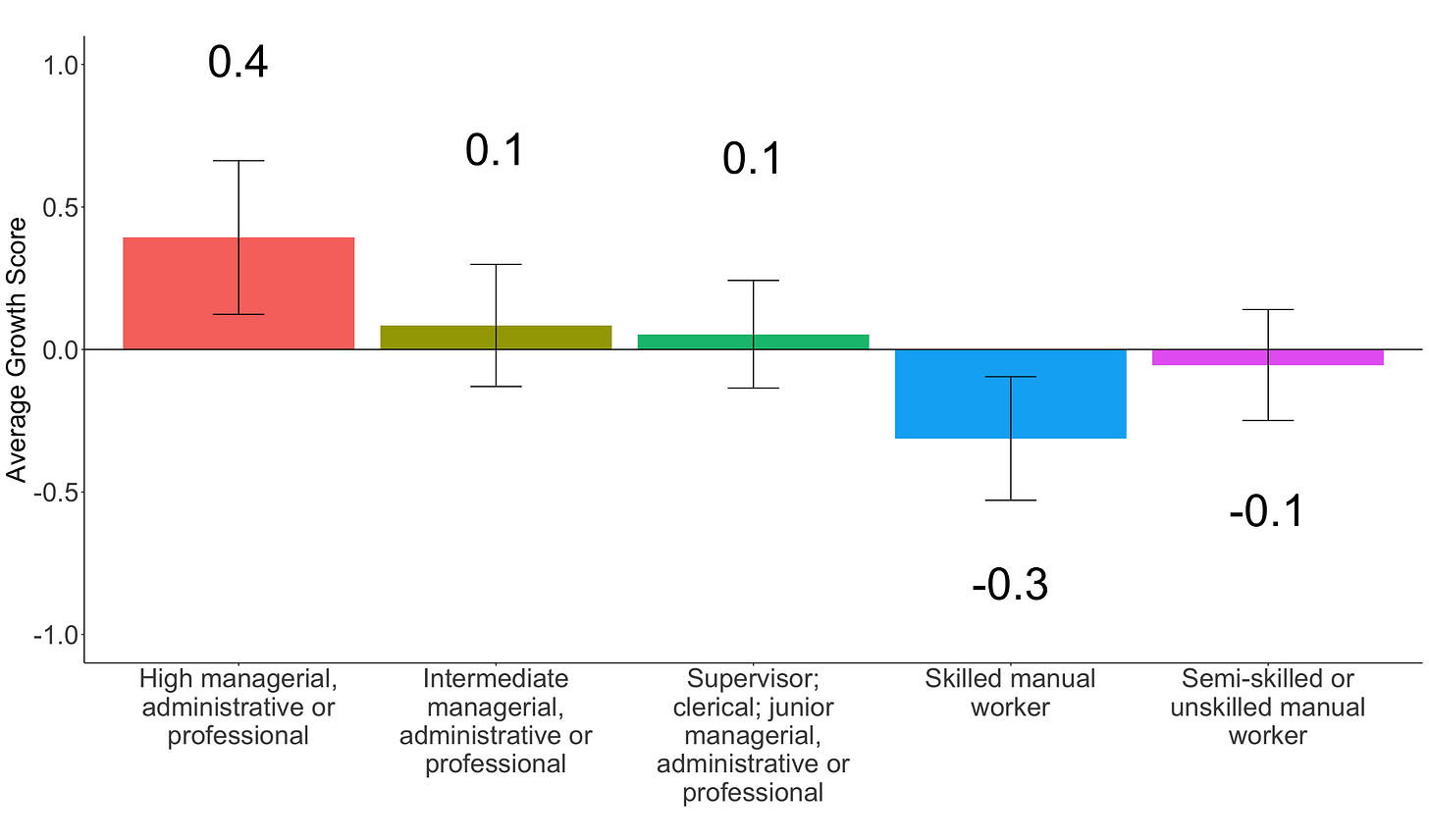

Growth as a Class Divide

Using people’s answers to the eight strongest growth statements, we created a single score for each respondent’s attitude towards growth using a “graded response model.” This method takes all their answers and combines them into one number that shows where they fall on the growth spectrum. A low score means a person is strongly anti-growth, a high score means they are strongly pro-growth.

We could then see which demographics are most associated with beliefs on growth. We tested age, gender, education, ethnicity, homeownership, marital status, work status, occupation, and the population density of the constituency that a person lives.

Doing this reveals that by far the best predictor is a person’s occupation, with people in the most elite jobs much more likely to hold pro-growth views. In contrast, it is skilled manual workers (rather than semi-skilled or unskilled manual workers) that are the most anti-growth.

Previous studies in economics suggest that recent waves of technology have tended to benefit workers doing non-routine cognitive jobs through higher earnings and employment.19 This could help explain why higher managerial, administrative or professional respondents were so positive, as they have benefited from growth in the past and may therefore think they will do so again in the future.

At the same time, MIT economist David Autor has found that technological change in recent decades has moved workers in “specialized middle-skill occupations into low-wage occupations that require only generic skills.”20 In other words, skilled manual workers who once had stable, well-paid jobs have been hit hardest by automation. This fits with our findings, where skilled manual workers are the most anti-growth. It makes sense that people in these roles are anxious about the future, given that past waves of growth and technological change have tended to disadvantage them.

This is different to those in semi-skilled or unskilled jobs (such as waiters, cleaners, those boxing items, or assisting the elderly) which are generally harder to automate, given that they tend to require either dexterity or communication skills that technology lacks, and so have not generally seen a decline in employment over the past decades.21 This could help explain why respondents in these occupations were less likely to hold anti-growth views than their skilled counterparts, as it would be less likely to affect their income or employment prospects.

Of course, the coming wave of artificial intelligence could have very different effects, targeting many of the white-collar jobs that were previously protected from automation. If that happens, all bets are off as the people who’ve been the strongest supporters of growth could find themselves among those most disrupted by it this time around.

Pro- & Anti-Growth Voters Go to Polls

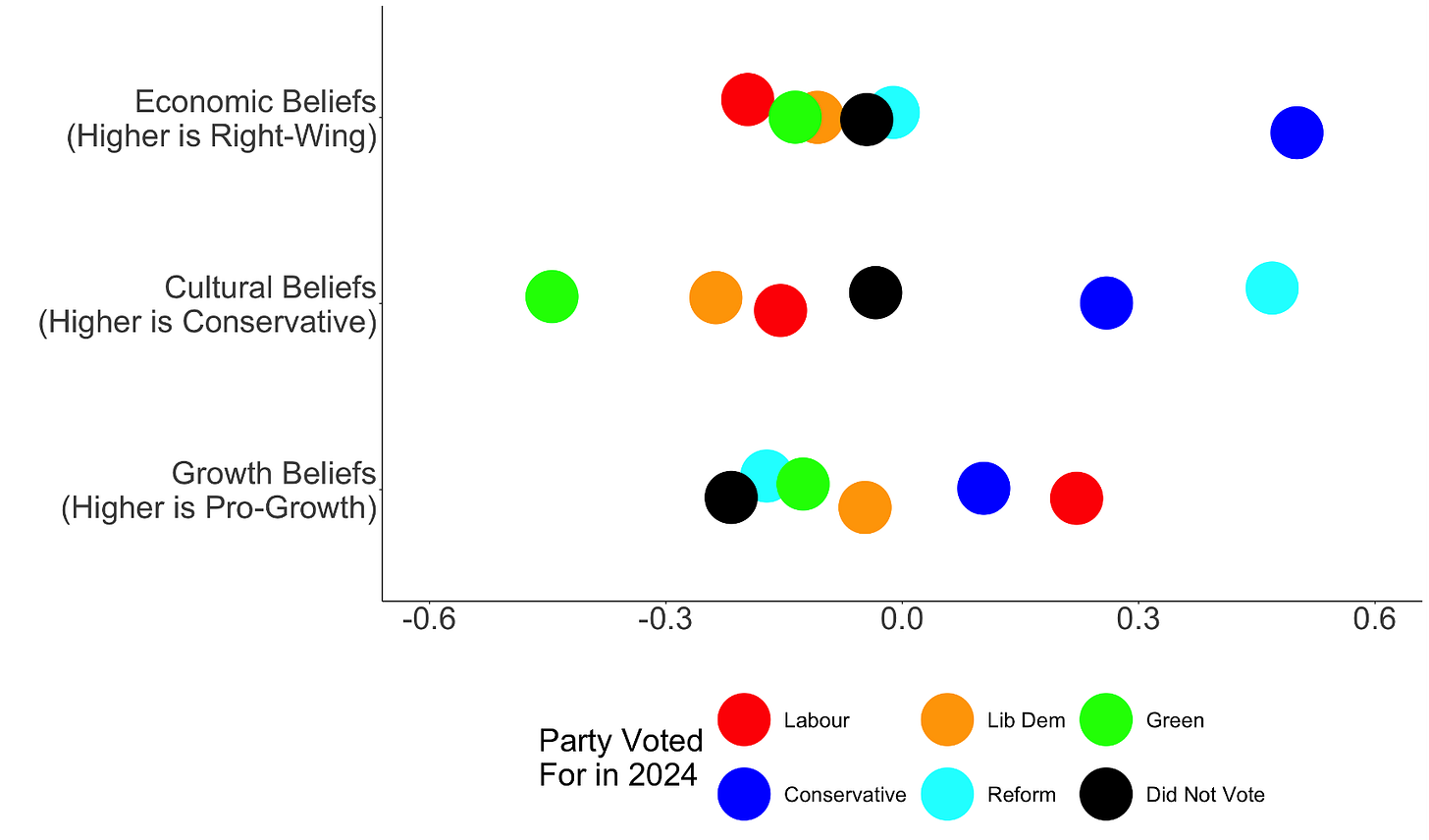

As growth attitudes don’t neatly align with existing political frameworks, how do they relate to voting behaviour? We can use each respondent’s score on the three dimensions (traditional economic, traditional social/cultural and growth) to see what the average was for each by how people voted in the 2024 general election.22

Labour voters are the most pro-growth group compared to others, followed closely by Conservatives. At the other end, non-voters, Reform voters and Green Party voters show the most anti-growth attitudes. Given how these parties’ voters have such different beliefs on the other dimensions, this gives further evidence of how growth beliefs do not map neatly onto traditional divides.

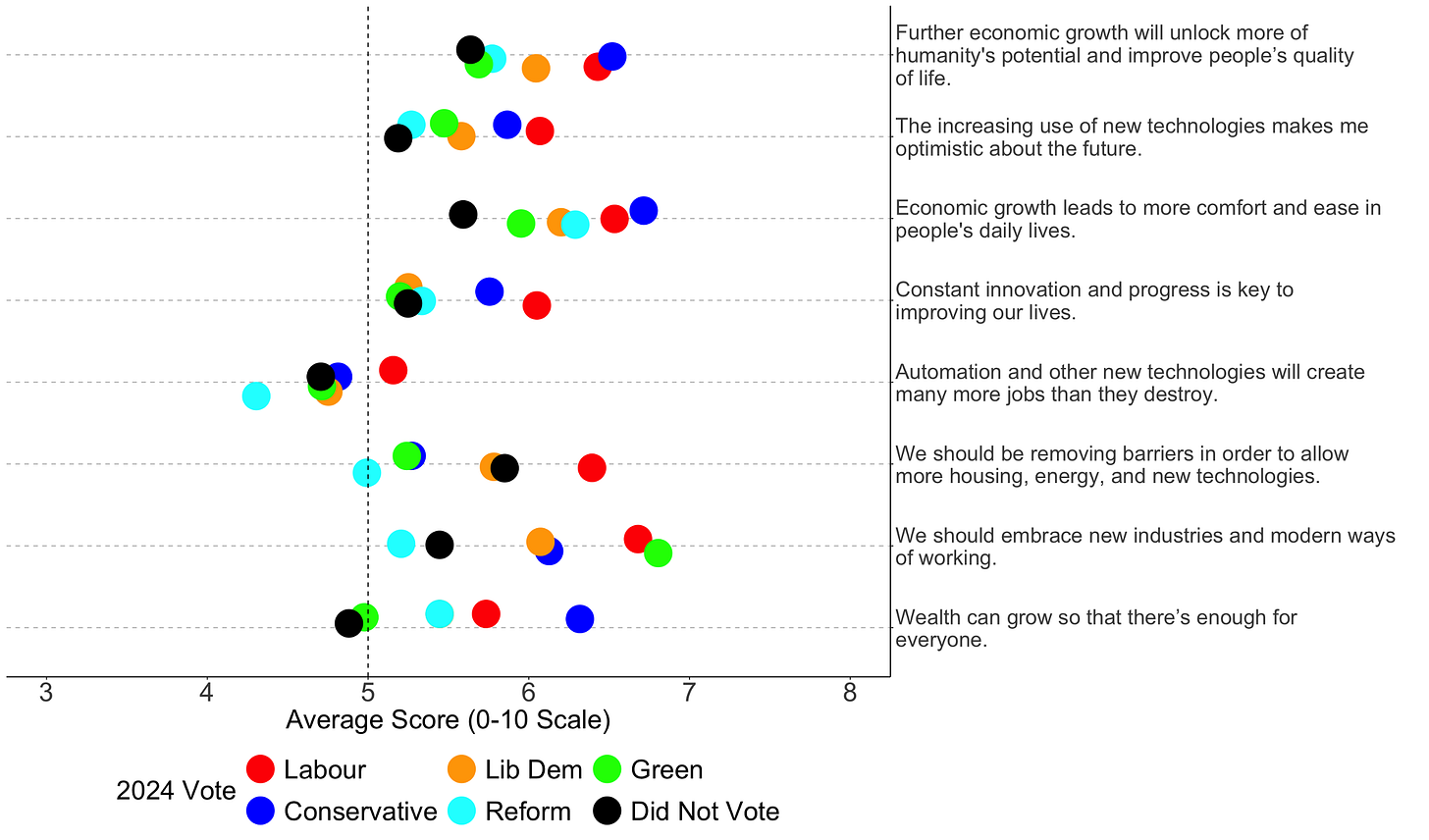

You can see this pattern when looking at answers to the eight growth statements. Labour and Conservative voters tend to swap places depending on the question, where sometimes Labour supporters come out as slightly more pro-growth, sometimes it’s the Conservatives. Non-voters stand out as consistently the most anti-growth group across nearly every question. After them, the next most anti-growth groups are either Green or Reform UK supporters, depending on the specific question.

Was Liz Truss Right?

There certainly is a group of voters who have more negative views about growth than others, but these are not necessarily the same people Liz Truss complained about when she was prime minister.

In reality, the anti-growth coalition looks like this:

It’s a mixture of Reform voters, Green Party voters, non-voters and skilled manual workers. On the one hand, Truss did name climate change activists as part of her anti-growth coalition, so our findings on Green supporters bear this out. However, Truss also named Remainers, but we found that Reform voters are consistently anti-growth and are one of the most pro-Leave groups in the country.

For the Greens, there was some surprise last year when their then co-leader Adrian Ramsey opposed the building of pylons through his constituency carrying wind energy. However our results show that this may be in line with Green supporters’ general opposition to growth, despite sometimes coming into conflict with pro-environmentalism.

The common thread among these disparate groups is likely to be scepticism towards the current political system. This sentiment can manifest in different ways – from voting for a right-wing populist party to voting for a left-wing environmental party to abstaining from voting altogether – but correlates here with pessimistic views on growth and development. This suggests that attitudes towards growth are intertwined with broader perceptions of the direction of society and how much influence they feel they have within the system. These feelings of alienation extend here to scepticism about the benefits of economic growth and technological progress.

In contrast, the pro-growth coalition is a mixture of people in comfortable middle-class occupations, Labour voters and Conservative voters. That’s awkward for Liz Truss, who labelled Labour as part of the “anti-growth coalition.” In reality, Labour supporters in our data were among the most pro-growth of all.

Some of that may be because, with Labour in power, their voters felt more upbeat about the future and confident that growth is back on the agenda. But it also shows that people don’t fit neatly into the caricatures politicians paint of them. Truss may have missed a trick by turning Labour supporters into enemies of growth, when the data suggests they were, at least in part, open to her message.

What stands out is that mainstream party supporters (Labour and Conservative) tend to see growth as a more positive thing than other parties’ supporters. Even if they clash on tax, spending or culture-war issues, they still share a belief that Britain should be aiming to grow.

This suggests that being pro-growth, supporting the main parties23 and feeling optimistic about the future tend to go together. It’s the opposite image to the anti-growth coalition, where scepticism about growth overlapped with scepticism about the political system itself. In other words, belief in growth isn’t only about GDP, it’s also about trust, optimism and whether people think the system can deliver for them.

Growth unites people who might otherwise disagree and divides others who would normally be on the same side. In that sense, understanding how people think about growth isn’t just about predicting elections. It’s about understanding how a society sees its own future, and whether it still believes that tomorrow can be better than today.

So, in conclusion…

Growth and Populism

Some of those in the pro-growth camp argue that economic growth is the cure for populism. The idea goes that if people see progress, innovation and abundance all around them, they’ll stop feeling angry, resentful or left behind.

That could be true at the end of the story if everyone shared in the benefits of that growth. But even if the abundance crowd are right in the long-run, they tend to skip over a pretty big detail: growth, technology and progress all come with enormous social change.

Populism often rises in the wake of big economic or cultural shifts. Saying “let’s put our foot on the accelerator” is, at best, a bold gamble. At worst, another round of disruption sold as “progress” isn’t an inspiring vision, it’s a threat.

Our data shows that the people most drawn to populist movements are, in fact, the most anti-growth. So if your plan to counter populism is to generate more growth (which would inevitably involve a lot of change), you’re pushing something that many of those voters actively distrust. In doing so, you’re creating an opening for populists to harden their support among anti-growth voters and deepen the divide.

It’s also a pretty emotionally unintelligent approach. You’re effectively telling people (once again!) that you know what’s best for them. This time it’s that growth and technological change are good and you just need to accept it. But that’s the same argument that failed in past debates over immigration: insisting that people welcome “inevitable” change for their own good, rather than taking their worries seriously.

If abundance advocates repeat that mistake with growth, they won’t be curing populism, they’ll be fuelling it.

The Future of Growth Beliefs

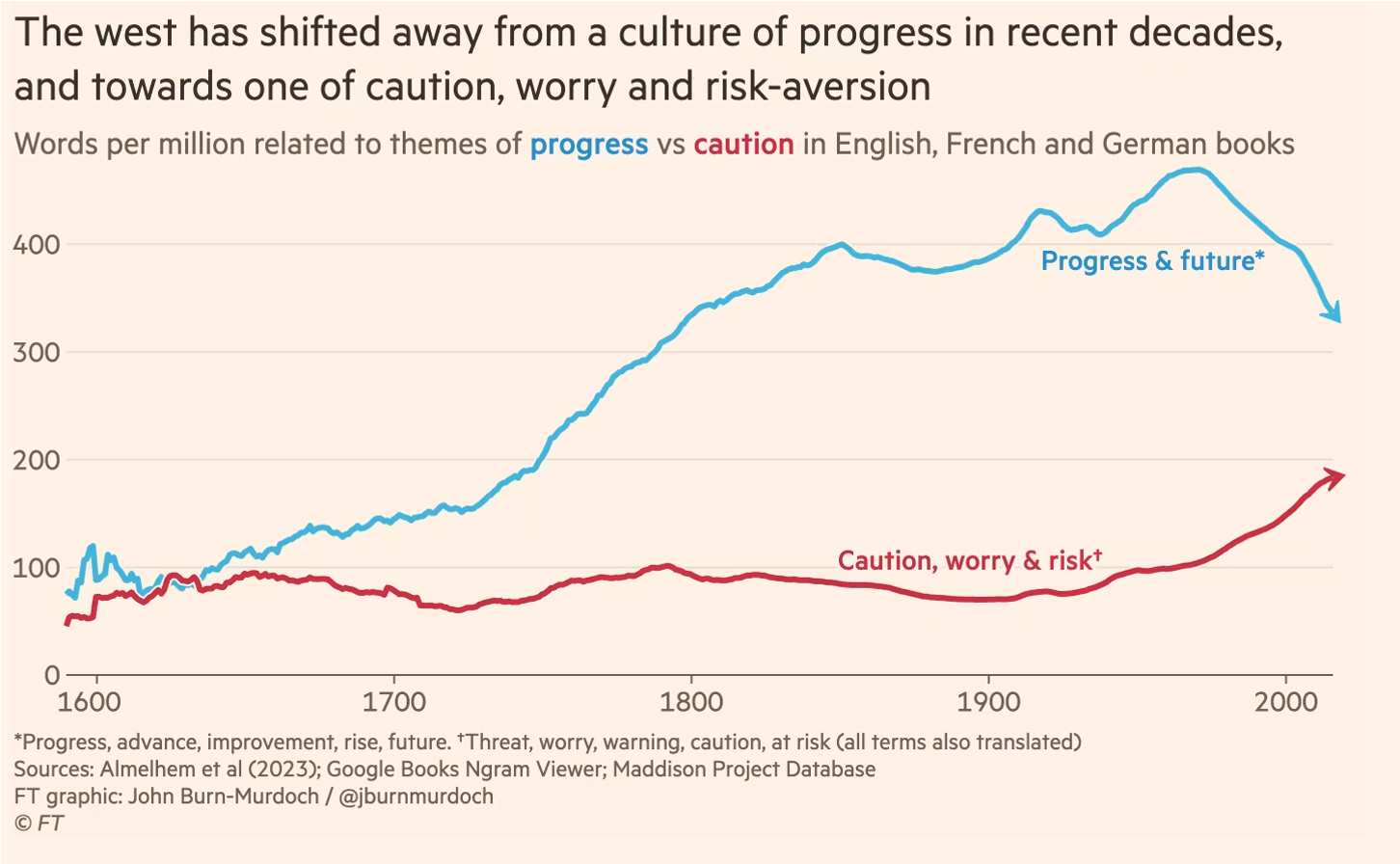

Economic historians have argued that optimism about the future and confidence in human ingenuity helped spark the Industrial Revolution in Britain.24 Between 1500 and 1900, the language of progress and innovation became far more common in books, reflecting and reinforcing that cultural shift.25 Since around 1970, though, there’s been a noticeable change. Analyses of books in English, French and German show a sharp decline in words associated with progress and a rise in those linked to caution and risk.26

Over the same period, growth rates in Western economies have slowed. Correlation isn’t causation, but it may be that our willingness to believe in the benefits of progress and technological change have played a quiet but powerful role in shaping that story.

In our data, the pro-growth camp tended to be those who feel optimistic about the future and confident in technological progress. Yet there’s a paradox here: optimism seems to depend on growth, but growth may also depend on optimism. When people lose faith that progress is possible, they become more cautious and risk-averse, which in turn makes progress harder to achieve.

So how do you break that loop? God knows.

Again, I’m sceptical that simply insisting that growth is good, or pushing through policies that people don’t trust or understand would work. You can’t lecture people into optimism.

I suppose the only real way to create more pro-growth believers is to deliver visible improvements in people’s lives. However, it would need to be growth that feels fair, tangible and worth believing in. If growth is yet another thing that some snobby, overconfident, university-educated London-dweller with a “vision for Britain” is doing to you without your input, it risks hardening the very scepticism it’s meant to overcome.

This connects directly to what we found about occupation. Class may have declined as a good predictor of voting behaviour in the UK but it clearly still shaped how people think about growth. However, this was not a simple working-class vs. middle-class divide but depended on how a person’s specific occupation is impacted by change. An increased saliency and campaigning on growth could create a class divide in voting, but in a more complex manner than the white-collar vs. blue-collar divide of old.

And Finally….

If you’ve slogged your way through the whole article, here’s a treat/punishment (depending on your thoughts) for you…

AI turning Liz Truss’s speeches as prime minister into pop music:

If you like this, there’s more where that came from in one of my previous posts.

I really enjoyed making it but it got hardly any views 😔

So please have a read 😁

Johan Norberg. The Capitalist Manifesto. Atlantic Books, 2023.

James Pethokoukis. The Conservative Futurist: How to Create the Sci-Fi World We Were Promised. Hachette UK, 2023.

Virginia Postrel. The Future and Its Enemies: The Future and Its Enemies: The Growing Conflict Over Creativity, Enterprise, and Progress. Free Press, 1998.

John Maynard Keynes. “Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren.” Essays in Persuasion. Palgrave Macmillan UK, 1930.

Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson. Abundance. Simon and Schuster, 2025.

David Leonhardt. Ours Was the Shining Future: The Story of the American Dream. Hachette UK, 2023.

Peter Kolozi. Conservatives Against Capitalism: From the Industrial Revolution to Globalization. Columbia University Press, 2017.

Friedrich A. Hayek. The Constitution of Liberty: The Definitive Edition. Routledge, 2011.

Rana Kabbani. Europe’s Myths of Orient: Devise and Rule. Springer, 1986.

Clive Hamilton. Growth Fetish. Pluto Press, 2004.

Klein and Thompson. Abundance

Marian L. Tupy and Gale L. Pooley. Superabundance: The Story of Population Growth, Innovation, and Human Flourishing on an Infinitely Bountiful Planet. Cato Institute, 2022.

Jon Moynihan. Return to Growth Volume One: How to Fix the Economy. Biteback Publishing, 2024.

Tom O’Grady. “Nimbyism as Place-Protective Action: The Politics of Housebuilding.” SocArXiv, available at https://osf. io/preprints/socarxiv/d6pzy (2020).

Patrick Devine‐Wright. “Rethinking NIMBYism: The Role of Place Attachment and Place Identity in Explaining Place‐Protective Action.” Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 19.6 (2009): 426-441.

Giorgos Kallis. Degrowth. Agenda Publishing, 2018.

Roger Scruton. How to Think Seriously About the Planet: The Case for an Environmental Conservatism. Oxford University Press, 2012.

Hannah Ritchie. Not the End of the World: How We Can Be the First Generation to Build a Sustainable Planet. Vintage, 2024.

Toby Ord. The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity. Hachette UK, 2020.

Peter H. Diamandis and Steven Kotler. Abundance: The Future is Better than You Think. Simon and Schuster, 2012.

Okay, that’s enough

David Autor. “The Labor Market Impacts of Technological Change: From Unbridled Enthusiasm to Qualified Optimism to Vast Uncertainty.” No. w30074. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2022.

David Autor. “Work of the Past, Work of the Future.” AEA Papers and Proceedings. Vol. 109. 2014 Broadway, Suite 305, Nashville, TN 37203: American Economic Association, 2019.

Maarten Goos, Alan Manning, and Anna Salomons. “Explaining Job Polarization: Routine-Biased Technological Change and Offshoring.” American Economic Review 104.8 (2014): 2509-2526.

Three separate graded response models on each dimension

Well, the main parties until recently

Joel Mokyr. The Enlightened Economy: An Economic History of Britain 1700-1850. Yale University Press, 2012

Joel Mokyr. A Culture of Growth: The Origins of the Modern Economy. Princeton University Press, 2016

Ali Almelhem, Murat Iyigun, Austin Kennedy, and Jared Rubin. “Enlightenment Ideals and Belief in Science in the Run-up to the Industrial Revolution: A Textual Analysis.” Social Science History (2023).

Fascinating research. That graph plotting the 8 issues and party vote is neat proof of how weird and disconnected the legacy parties seem to people not highly engaged with politics, and how the relative extremism of the legacy parties presumably discourages voting. On all but one issue, the non-voters are closest to either Reform or the Greens (or both), and far away from Lab and Con.