The Nine Different British Voters

What they say about the 2024 result and what they might say about the future...

Hello there! 😀

I’ve started this Substack to share some analysis of public opinion and voting, but hopefully without the stuffiness of academic articles.

In this first post, I’ll be going into the different ‘segments’ of British voters and how they helped shape the outcome of the last election. I’ll focus mainly on Conservative, Labour, and Reform voters this time around, but am planning to do something on the Lib Dems in my next post (whenever that is).

You’ve probably heard labels like ‘Mondeo Man,’ ‘Pebbledash People’ or ‘Waitrose Woman’ used when discussing British politics. These are usually made by political parties or think tanks to give a snapshot of a target demographic in an election. But the downside of this is that they only describe one very specific type of voter, rather than analysing the entire electorate as a whole.

Luckily, there are also ways to take a broader look, using survey data to identify patterns across the population.

Here, using data from the 2024 general election, I’ll run some analysis to see what kinds of voter groups emerge, what this says about the result and what it might say about the future.

Hope you enjoy the read!

Playing Four-Dimensional Chess with British Voters

Political beliefs are usually summarised using two dimensions:

Economic attitudes running from left (support for redistribution and state intervention) to right (support for free markets and lower taxation).

Social/cultural attitudes ranging from liberal (support for individual freedoms and social change) to conservative (preference for tradition, order and stability).

This is a really useful starting point for anyone thinking about public opinion and gives you a much better understating of beliefs than using just a one-dimensional left-right scale.

However, it doesn’t capture everything.

Political behaviour can’t just be explained by policy preferences – it’s also about how people engage with politics. Two voters might share the same economic and cultural views but one feels empowered and engaged, while the other feels disconnected and distrustful.

Fortunately in the UK, we have the British Election Study Internet Panel (BESIP) which has been running since 2014. This is a massive survey run every 6-12 months that gathers detailed information about each respondent and their political beliefs, providing the depth you can’t get from simpler polls.

As well as questions on people’s economic left-right and social liberal-conservative1 values, the BESIP also includes questions that capture people’s attitudes on:

Efficacy: this essentially means how much you feel your political participation matters. People with high efficacy believe they can influence politics and that the system responds to them. Those with low efficacy feel powerless or disengaged.

Populism: based on a widely used scale developed by political scientists Cas Mudde and Agnes Akkerman, this measures how much people see politics as a struggle between ‘the people’ and a corrupt or out-of-touch ‘elite’.

In the run-up to the 2024 UK general election, BESIP2 conducted a survey covering four key political dimensions.3 This allows us to build a detailed picture of British voters.

To do this, we can use statistical methods to assign each person a score on all four dimensions.4 Once we have these scores, the next step is to group people based on how similar they are. But how many groups should we use?

Rather than guessing, we can use a method that tests different possibilities and identifies the best fit.5 Based on this, it suggests that British voters can be divided into nine distinct groups each with its own political identity:6

Alienated

Disengaged

Libertarians

Middle

New Left

Old Left

Social Democrats

Thatcherites

Tories

Who Are Ya?

Below is where each group sits on average for the different dimensions.7

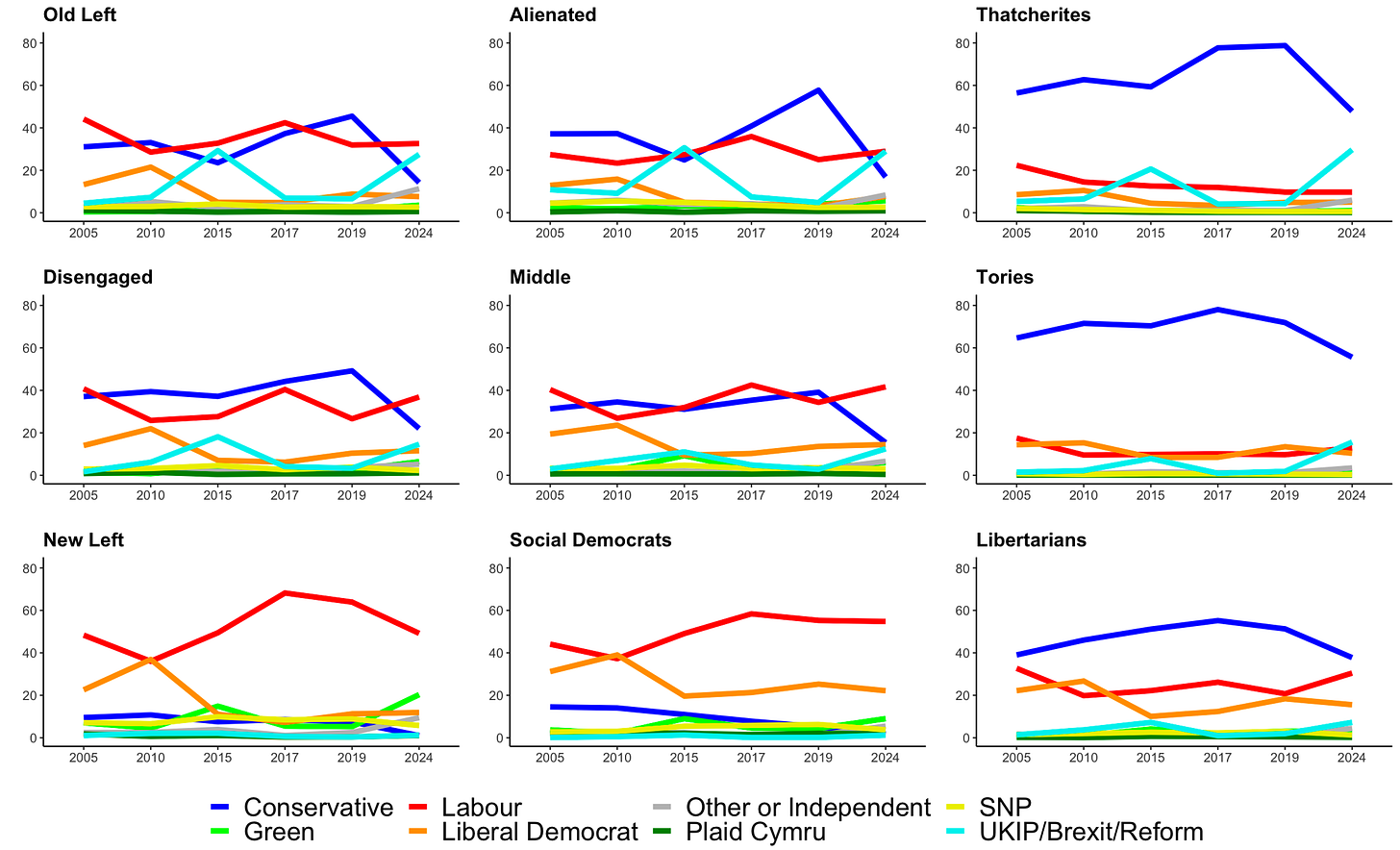

And this is how they voted in each UK election since 2005.

This gives more demographic information for each of the nine groups.

And, because this is Britain and class is everything, here is which occupations each of the groups work in.8

New Left

Very economically left-wing and socially liberal, the New Left is politically engaged and leans populist. Making up 10% of the population (12% of voters in 2024 due to high turnout), they have consistently backed Labour, except in 2010 when they split with the Lib Dems. In 2024, Green support grew but Labour remained dominant.

The youngest and most diverse group, they have low homeownership. There is polarisation in what job they do, with both the joint second highest percentage in higher professional occupations, but also the second highest in semi-routine jobs.

Politically, this group best represents what is often labelled as the ‘woke’ left.

Social Democrats

Sharing similar policy views with the New Left but differing in temperament, Social Democrats trust institutions and feel politically empowered. Making up 7% of the population (11% of voters due to very high turnout), they are a Labour stronghold and, unlike the New Left, showed no real shift toward the Greens in 2024. Almost all (92%) voted Remain in 2016.

Predominantly male, highly educated, and financially secure, they dominate professional and managerial roles.

If any group embodies the liberal-left elite, this is it.

Tories

Defined by their right-wing economic views, Tories are politically engaged but anti-populist. They make up 6% of the population but 9% of voters in 2024. They remain the Conservatives’ core base, though slightly weakened in 2024. In 2016, they were split on Brexit (49% Leave, 51% Remain).

The whitest group, they are also older, mostly male, and university educated. They have high homeownership and by far the highest percentage in higher managerial jobs or as employers in large organisations.

If any group embodies a right-wing capitalist elite, this is it.

Thatcherites

Economically right-wing and socially conservative, Thatcherites are populist and politically engaged. They are 10% of the population (12% of voters). A historic Conservative base, but with strong backing for UKIP in 2015 and a major shift to Reform in 2024. They had the highest Leave vote in 2016 (81%).

An older group, they have low university education but high homeownership. They are overrepresented among small business owners and the self-employed.

This group embodies petit-bourgeois lower-middle class populism – feared and resented as those most likely to turn to fascism by the left, but defended and championed as the economic backbone of the country by the right.9

Old Left

The Old Left pairs left-wing economics with strong social conservatism. Having moderate political efficacy and high populism, they make up 8% of the population and 9% of 2024 voters.

Their voting patterns have been fluid: evenly split between Labour and the Conservatives from 2010 to 2017, then leaning Tory in 2019. However, in 2024, Conservative support collapsed, Reform surged, and Labour held steady. 75% backed Leave in 2016.

Older, predominantly male, and working-class, they are concentrated in semi-routine and intermediate jobs.

This segment best represents the ‘traditional working-class.’

Libertarians

Right-wing on economics and moderately liberal socially, Libertarians have low populism but also low political efficacy. They make up 13% of both the general population and voters.

They were firmly Conservative from 2005 to 2019, but in 2024, support plummeted, leaving them much more split between Labour and the Conservatives. They were slightly pro-Remain (56%) in 2016.

With a high proportion of women and homeowners, they are more concentrated in lower managerial, intermediate and self-employed jobs.

Perhaps they best capture voters with a ‘live and let live’ attitude.

Middle

About average on economics, social issues and populism, but with above-average political efficacy. They are 12% of the population and the largest voting bloc at 15%.

Their voting tends to mirror national trends. Between 2005 and 2019, they were split between Labour and the Conservatives, but in 2024, Labour gained a commanding lead as the Conservative vote collapsed. 55% backed Remain in 2016.

Demographically, they are average across most characteristics, making them a relatively representative cross-section of the electorate.

This group best represents the average voter that is not committed to any party or ideology and is willing to switch from election to election.

Disengaged

The Disengaged also sit near the average on economic and social views, as well as populism. However, their defining feature is very low political efficacy. The largest population group at 19%, their low turnout drops them to 13% of voters.

Their voting behaviour is very similar to the Middle group, though they have been slightly more Conservative leaning. In 2019, the Conservatives had a strong lead, but in 2024 their vote collapsed. Labour’s vote stayed at similar levels, but this meant they had a dominant lead. This group tended to back Leave in 2016 (63%).

Mostly female, with lower education and incomes, they are overrepresented in intermediate and semi-routine occupations.

This is the apathetic voter, disaffected with politics and not strongly ideological.

Alienated

The Alienated share generally the same economic and cultural views as the Old Left but are even more populist and have very low levels of political efficacy.

They are 14% of the population but were only 7% of voters in 2024 due to very low turnout. They leaned Conservative pre-2019, but with strong UKIP support in 2015. In 2024, their vote fragmented, pushing many toward Reform. Labour’s share remained stable, but its relative position improved.

This group has the lowest levels of university education and household income, as well as low rates of homeownership. They are overrepresented in technical jobs, semi-routine and routine jobs, as well as being virtually absent from higher managerial and professional occupations.

This is the group that embodies the ‘left behind’, deeply distrustful of elites and increasingly drawn to populist alternatives.

Divided by Politics

Immigration

Immigration has been one of the most contentious and important issues in British politics for decades.10

Opposition to increased immigration is the near universal preference of the clusters, albeit to different levels.11 The strongest opposition comes from Alienated, Thatcherites and the Old Left. New Left and Social Democrats stand out as the only groups that support increasing immigration, but even then it’s not to a particularly high level.

There is evidence that the public became more pro-immigration after the Brexit referendum.12 I think a more accurate description would be to say that they became less anti-immigration starting from a very low base in 2016. Even then, immigration sympathy peaked in early 2022 and has been falling ever since.

Brexit

Similar to immigration, Brexit remains a fault line in the electorate.13

This looks pretty similar to immigration attitudes, with the New Left and Social Democrats again standing out by supporting EU integration to a much higher degree than anyone else. Thatcherites are the most strongly anti-EU group, followed by the Tories and the Alienated.

This result is why I think you should be cautious when looking at polls that show the UK public are gagging for a closer relationship with the EU. Having two segments of the electorate which are very pro-EU will push up the aggregate score, giving a distorted view of where overall national opinion is if you just look at the headline number.

What matters are the opinions of the non-ideological centre (particularly the Middle and Disengaged). There will only be actual demand for closer integration when these groups are much more in favour.

The Culture War

Since around the mid-2010s, ‘culture war’ issues have become a feature of political debate in Britain.14 Among these, transgender issues (particularly the question of sports participation) have received a lot of attention.

This is, to put it mildly, not the most popular policy in the world. Opposition is overwhelming in almost all groups, particularly Thatcherites, Tories and the Old Left. Social Democrats are less opposed, but the majority are still against. The New Left are the only group where opposition is not the majority, but much less than half actually support transgender inclusion in female sports.

Anyway, if you thought that was controversial…

Israel-Palestine

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict became a flashpoint in British politics after 7th October 2023, with Labour losing significant support among Muslim voters at the 2024 election to pro-Palestine independent candidates.15

Support for the Palestinian side is strongest among the New Left and Social Democrats. On the other hand, the Thatcherites and Tories are the most sympathetic to Israel. However, all other clusters were much more neutral on the issue.

Tax and Spending

The size and role of the state is foundational to the traditional left-right divide.

Support for higher taxes and more government spending is strongest among the New Left and Social Democrats. The Middle, Old Left, Libertarians and Disengaged and also lean in favour of higher spending, but with less intensity. On the other end, Thatcherites and Tories are the much more sceptical, wanting things to stay the same on average.

Notice that the Alienated have the lowest score, despite being generally on the economic left. This suggests that support for government tax and spending is not just a function of your policy preferences, but is also informed by how much trust you have in politics, given that this group has very low efficacy.

Overall, though, results lean much more towards more tax and spending. It highlights a broader truth about British politics: the public, on the whole, are pretty economically left-wing.

The Political System

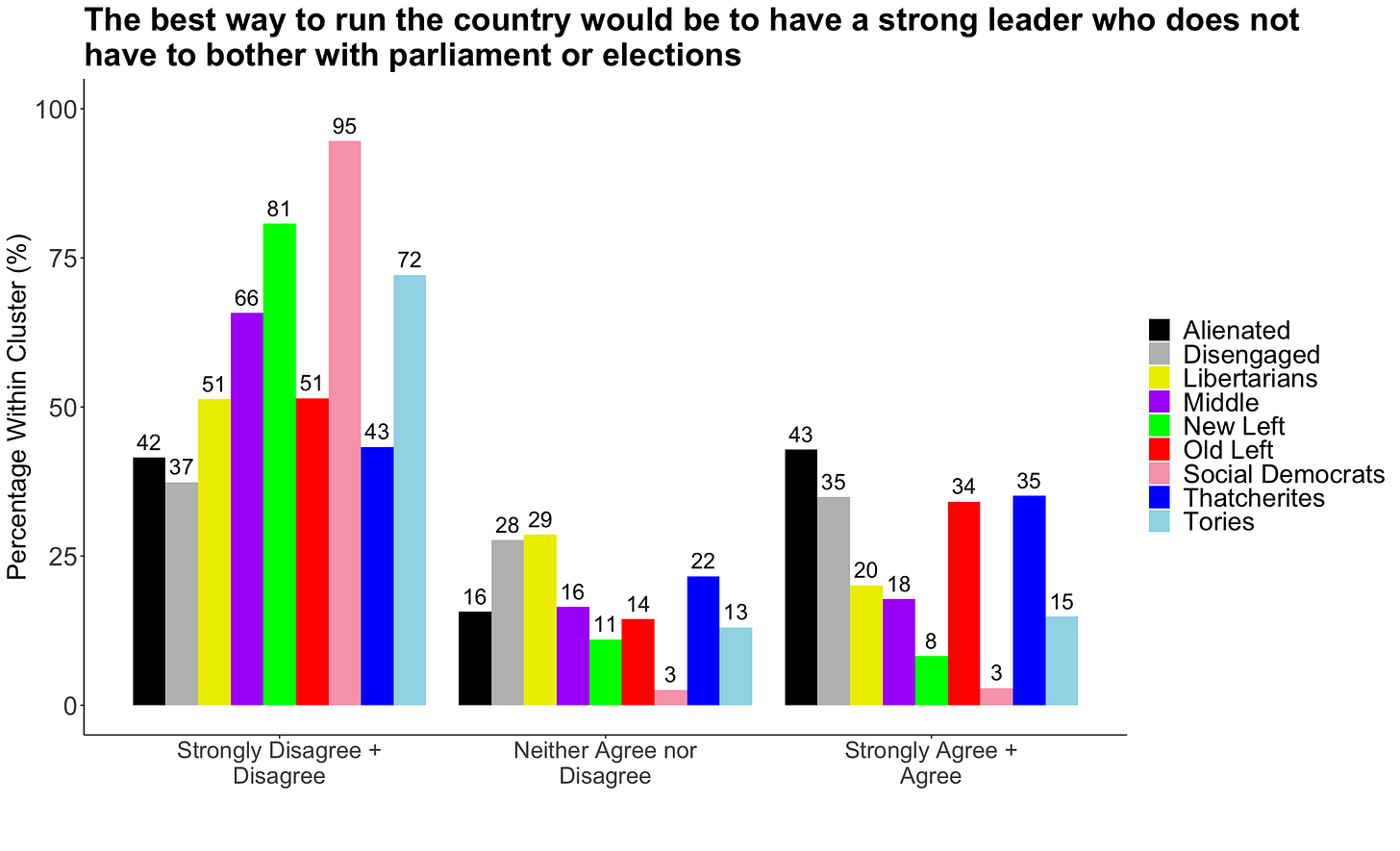

Recently, there was a report that suggested over half of ‘Gen Z’ wanted a ‘strong leader who does not have to bother with parliament or elections’. People who work for the British Election Study looked into this and found that there was no evidence for this in the BESIP. Here is this question with our groups.

The Alienated are the most enthusiastic about authoritarian leadership with almost half in support. At the same time, Social Democrats are the most opposed with almost all disagreeing.

On a similar note, the BESIP also asked whether people believe Britain needs fundamental change.

The vast majority in almost all groups agree, particularly the Old Left and Alienated. The only group that is even vaguely disagreeing are Tories. This can partly be explained by the fact their preferred party was the government – but, even then, there are still almost half of Tories agreeing.

To be fair, this is quite a vague statement that can be interpreted in different ways, but the key takeaway should be that Britain (on the left and right) is restless and unhappy. People are desperate for change.

Holy Valence! How the Conservatives Kiss-Kissed Their Majority Goodbye

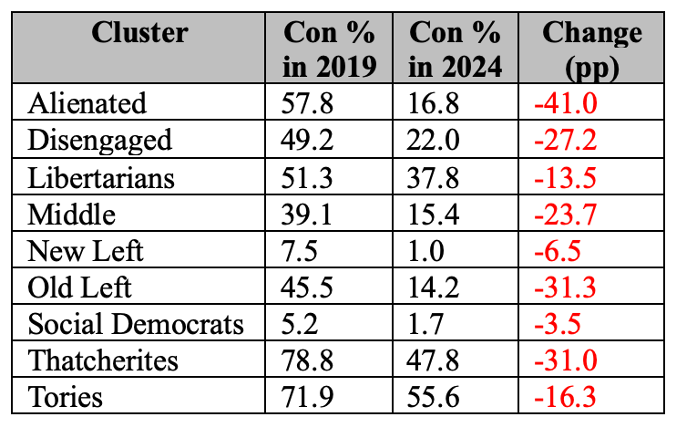

So far, most groups have a tendency to express preferences for right-wing policies, especially on non-economic issues like immigration. And yet a Conservative government suffered a generationally bad defeat.

The answer lies in a key political science concept: valence.

‘Valence’ means how competent and trustworthy a party is perceived to be. For the Conservatives, the 2024 election was lost because so many voters stopped trusting them on the issues they cared about and didn’t think they were competent enough to deliver on what they were promising.

Most Important Issue

To understand voter priorities, the BESIP asks respondents what they see as the single most important issue facing the country.16

Immigration, economic issues and the NHS were the dominant topics. Immigration was particularly important for Thatcherites, Alienated and the Old Left, while economic issues (the cost of living and the overall economy) were crucial for Disengaged and Libertarians. Healthcare issues were also named in almost all groups’ top 4.

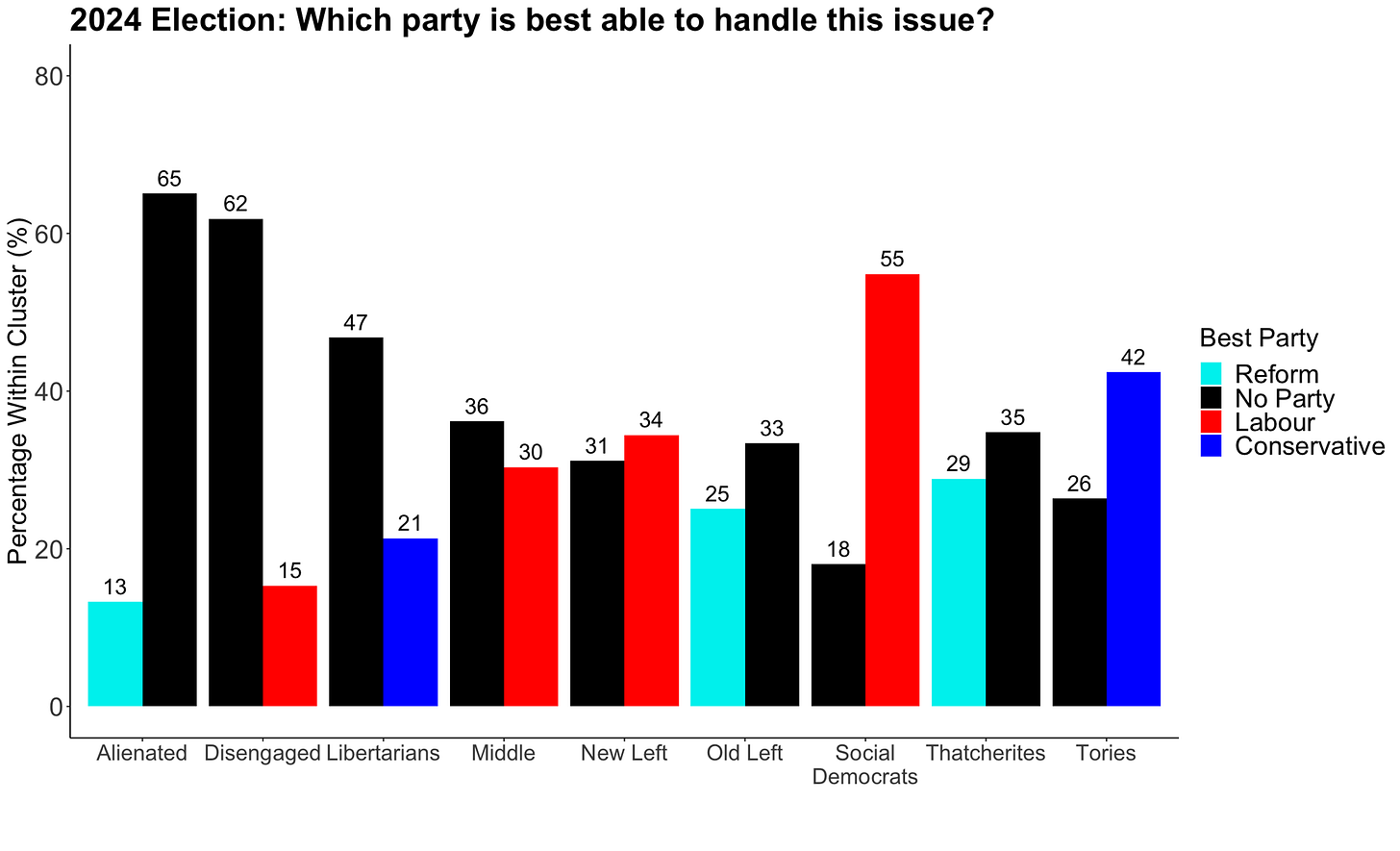

But the real question is who voters trusted to handle these issues.

Among the Alienated, Disengaged, Libertarians and Thatcherites, the largest response was that no party was competent enough to handle their most important issue. For the Old Left and Alienated – two groups the Conservatives had finally won decisively in 2019 – it was Reform who were named as the best party. The crucial Middle swing segment most frequently named Labour if they named a party at all.

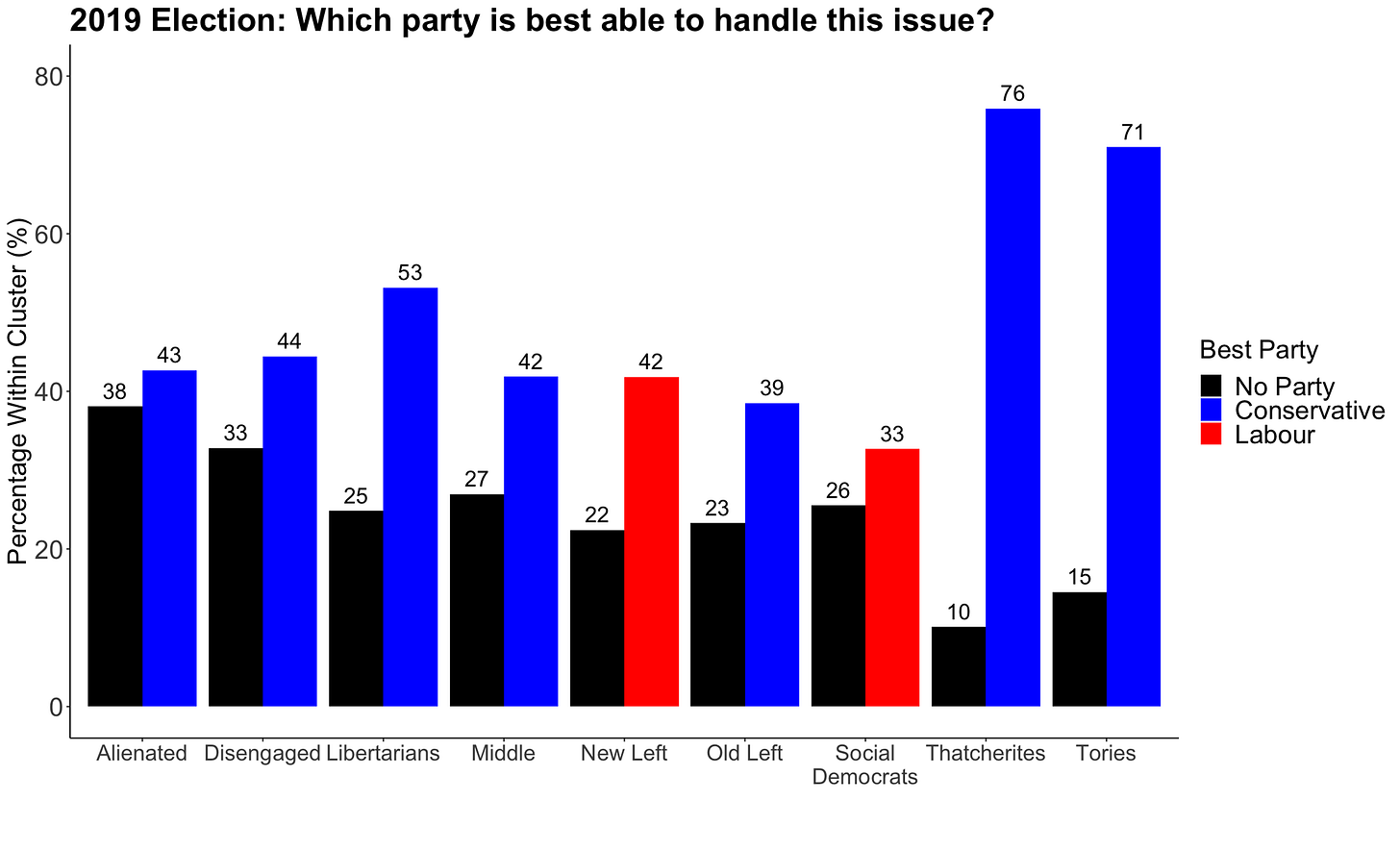

To show just how bad this was for the Conservatives, we can look at how our respondents answered the same question during the 2019 election.

Back then, the Conservatives dominated. The Alienated, Disengaged, Libertarians, Middle, Old Left, Thatcherites and Tories all saw the party as best to handle their top issue. Labour only had strong backing from the New Left and Social Democrats – and were not in the top two for crucial swing segments like Middle or Alienated.

5 years is a long time in politics.

The Big Three: Immigration, Economy & NHS

Three core issues defined competence at the 2024 election:

Immigration

Economy

NHS

On all three, the Conservatives suffered huge losses in public trust.

First, the BESIP has, since 2016, tracked whether voters believed the Conservatives would successfully reduce immigration in government.

Boris Johnson restored confidence from the 2019 election to the start of 2022. However, by 2024 – after the ‘Boriswave’ of legal migration and the government self-evidently not ‘stopping the boats’ – this reputation had crumbled amongst the clusters who wanted immigration reduced and was at similarly low levels to before the 2016 EU referendum.

This loss of confidence was so damaging because there was now a credible alternative in Reform for anti-immigration voters.

As trust in the Conservatives disintegrated, trust in UKIP/Brexit Party/Reform increased. Anti-immigration voters had an obvious outlet for their frustrations with the government and were able to move to a party they believed could actually deliver on their priorities.

Second, of all issues facing governments, economic competence is often the most decisive in determining election outcomes.17

Across almost every voter group, there was overwhelming dissatisfaction with the government’s economic management. Among the Alienated, Disengaged, Middle, and Old Left, between 67% and 84% of voters said the government had handled the economy ‘very badly’ or ‘fairly badly.’

Tories and Thatcherites were the only groups that showed support for the government’s economic policies, but this was barely half of Tories and much less than half of Thatcherites.

Finally, the BESIP therefore voters whether they believed any party would be successful in reducing NHS waiting lists.

Labour was seen as by far the most competent party, with majorities or pluralities in almost every group. Even Thatcherites were pretty evenly split between trusting Labour and the Conservatives – being the only group where the plurality trusted the Conservatives. Among Tories, only 25% believed the Conservatives were the best on the NHS, but Labour were ahead of them at 30%.

What Does This All Mean?

1. The Conservative Party is in a dilly of a pickle

It’s not an exaggeration to say that the Conservative Party is in the most precarious position it has faced in over 100 years.

This is not a simple case of the party being out of step with public opinion on key issues. Instead, the problem is far worse: voters no longer trust the Conservatives to govern.

This distinction is crucial. If a party’s problem is policy positioning, the solution is straightforward: reposition on major policies and win back support.

But when a party is seen as incompetent, it loses across the board.

If a party’s policies are out of step with public opinion, it should still only lose votes from one end of the electorate. A Conservative Party that is ‘too right-wing’ might lose centrist voters but would at least still maintain strong support among right-wingers. A Conservative Party that is ‘too left-wing’ might alienate traditional supporters but would hope to pick up centrist voters.18

Being seen as incompetent means everyone abandons you, regardless of your policies. If you promise ‘right-wing’ things, centrists won’t like you because they disagree with you and right-wingers don’t like you because you’ve failed to implement them – and vice versa if you promise ‘left-wing’ things.

Sunak’s five key pledges19 were all popular in the abstract. I’m sure they were polled and focus grouped to death, and chosen because they reflected widely held public concerns. The problem was not that voters disagreed with the objectives, but that they had no faith in the Conservatives to achieve them.

The Conservatives would keep making promises to prevent further electoral losses. This raised public expectations that the issue would be sorted out. Then, through inaction or incompetence, they would fail to deliver. As a result, voters would look for alternatives. Desperate to stem the bleeding, the party would then make yet another promise, starting the cycle all over again. This happened on immigration, the NHS, tax, economic growth, and basically everything else.

It was possible to break this doom loop. The only things that are impossible are things which break the laws of physics. It was operationally, logistically, physically and (with some changes) legally possible to, for example, stop the boats. It might have required a political fight (at least with New Left and Social Democrat figures) and required some big legislation, but it was not impossible if you were committed to doing it.

Instead, the government pursued a performative posturing approach while pushing the ineffectual Rwanda scheme. The result was that boat crossings remained high and voters saw through the government’s promises.

If you want to break the valance doom loop you need to:

Have a clear idea of your desired outcome and be committed to delivering it

Understand how the levers of power work in order to achieve this

When needed, make legislative changes and/or (very big and long-lasting) structural reforms to the civil service20

Develop a coherent plan of implementation

Get people with experience of successful project management and operations to get the job done

The last government did this with the Covid vaccine (and received a big increase in public support in the process) and that’s pretty much it.

The party now faces a paradox: voters will not elect a party they see as incompetent, but the only way to prove competence is in government. This creates a vicious cycle, because if people do not trust the Conservatives to govern, they will not get the chance to fix their reputation in Downing Street.

The depth of this crisis becomes clearer when considering the specific issues on which the Conservatives lost trust. Failing on traditionally Labour-dominated issues like the NHS is damaging enough. But the party also failed on core right-wing issues too. At a bare minimum, a normie centre-right government should make sure that:

The tax burden doesn’t increase

Immigration is controlled

Petty crime doesn’t go mass unsolved and unpunished

Instead, the last Conservative government delivered the exact opposite of what their voters wanted. This is why even the core right-wing clusters looked elsewhere in 2024.

Despite this situation, the approach of the party’s new leader Kemi Badenoch has been… leisurely.

I understand the logic of this. When you’re coming off a historically unpopular government, keeping a low profile might mean the strong feelings people had about you start to dissipate. You don’t want to keep popping up reminding people why they hated you so much. And, to be fair, she has an example in the former leader of the opposition (Keir Starmer) in how ignoring calls to be ‘bolder’ and not rushing things can work out in the end.

However… this really doesn’t seem to grasp the urgency of the Conservative predicament. A slow, cautious approach shows she thinks the party can gradually rebuild over time. But this is not an ordinary time.

After Labour’s 1997 landslide, it took the Conservatives more than a decade (and a major global financial crisis) to regain enough credibility to form a government. Even then, they only scraped together enough seats for a coalition with the Liberal Democrats.

And unlike the post-1997 period, the Conservatives now face a major right-wing challenger in Reform. Keeping silent and hoping to win by default in the face of an incompetent Labour government is no longer viable. They are genuinely in danger of becoming a third- or fourth-placed irrelevance.

However… the alternative approach is also a risk: make a big song and dance about how much of a clean break you are with the last government in order to send a clear signal to voters that you can be trusted, particularly on immigration, crime and the economy. This makes total sense in theory given how unpopular the government was and how toxic the Conservative Party is. If they pulled that off and became disassociated with the last government, then fantastic for the Conservatives because they could then start to properly re-build.

In practice, it’s risky because the more you talk about, for example, immigration (even if it’s to repudiate the last government), the more you remind the public about the last government’s record. Net migration in 2023 was 906,000 (!!!) so Starmer can go into the next election with immigration at even 450,000 and still legitimately say that he has halved immigration. If Badenoch/Jenrick/whoever tried to campaign on immigration, any Labour or Reform figure can turn around and just say ‘900,000’ and the public will once again be reminded just how bad their record was last time.

‘Conservatives shouldn’t fight on Farage’s turf.’ But it’s only become his turf because of their record in government.

And, anyway, what even is Conservative Party ‘turf’ these days? As I said, the party failed on basically all right-wing issues. Tax? Economic growth? Crime? You don’t want to remind people of your record on these things!

The only area where they had a positive long-term record was the English school system. Bridget Phillipson is now inexplicably trying to overturn these (and Andrew Adonis’s) reforms, so the Conservatives have a record that they can defend and attack Labour with. But education is a low priority for voters, so any gains they could make with this are limited.

And to make matters worse for them…

2. Reform’s ceiling is a lot higher than 25%

Reform is currently polling at around 25%, but there is a strong reason to believe its potential support is far higher if they play their cards right. They could crush the Conservative Party and take a decent chuck of voters from the other parties too.

The only cluster that is completely out of reach for them are Social Democrats. This group (liberal, progressive, pro-establishment and strongly opposed to populism) is never going to be drawn to the party. However, for all other groups, you can make the case that Reform has the potential (even if an outside chance) to expand its appeal.

Thatcherites already showed significant movement towards Reform in 2024. Their populist leanings and social conservatism make them natural sympathisers. In particular, they are strong supporters of controlling immigration and were deeply dissatisfied with the Conservatives’ handling of the issue. Reform should continue to resonate, particularly if Starmer is not able to ‘stop the boats’ either and the issue continues to be salient.

For the Old Left, the Conservatives always reached a ceiling due to residual partisan anti-Conservative sentiment. Reform does not carry the same historical baggage, so should be able to keep making progress with this group by focusing on social conservatism and a populist anti-system appeal.

While this group is economically left-wing, my own academic research suggests voters like this prioritise social conservatism (especially on immigration and asylum) over economic policy. Even then, Farage has been speaking more in support of certain left-wing economic policies like nationalisation and domestic manufacturing.

A huge prize but significant challenge for Reform lies with the Alienated and Disengaged. Both are defined by their distrust of the political establishment, making them natural targets. For those who voted in 2024, Reform made major inroads.

However, although they are both big segments of the population as a whole, these groups had by far the lowest turnout rate in 2024. The big task for Reform is whether they can mobilise voters who feel disconnected from the political process. The success of Donald Trump’s campaign in 2024 shows that right-wing populism can effectively energise low-propensity voters, but it takes unique political skills to do so.21

Reform faces challenges with the Middle segment, who have average views on all four dimensions, but it all really depends on the context of the next election. If Starmer has been unsuccessful in delivering and his government is unpopular, this will likely mean there is a strongly anti-establishment and pro-populist mood in the electorate as a whole (if there isn’t already). Given that the Middle tend to move in line with national trends, there’s a good chance that this group would be open to voting Reform in such an atmosphere.

While Libertarians tend to be socially liberal and anti-populist, they are also characterised by low political efficacy. If Farage can tap into this sense of disenfranchisement, there could be opportunities for progress.

A challenge for Reform is attracting more Tories. This group is pro-establishment and resistant to populism. Even though many agree with Reform’s policies, many are turned off by the party’s tone and general approach.

However, there is an important caveat. Tories’ priorities lean heavily towards economically right-wing policies. If Reform consistently polls higher than the Conservatives, they might begin to view Reform as the best (or only) viable option to implement the economic agenda they favour.

There is also an audacious outside chance of making inroads with the New Left – or, more accurately, people who used to be New Left. While the policy distance between Reform and this group is vast, history shows that the journey from youthful Marxist to middle-aged social conservative is not uncommon.22

Again, it’s best to think about the four dimensions. The New Left may be socially liberal and economically left-wing but they are also populist. If someone was drawn to the New Left because of its anti-establishment energy (such as for Corbyn in 2015 or 2017), what happens when that energy moves to a different political party? Take this recent post from Novara Media’s Aaron Bastani:

40% is way too high for all Corbynites, but I genuinely would not be surprising if a small minority of former Corbyn fans (who are still as disillusioned with the establishment and political elite as they were in 2015-19) decide to make a shift to Reform. Farage even recently praised Corbyn for being ‘anti-establishment’ and suggested this is why there was cross-over appeal between the two of them.23

Fundamentally, one reason why Reform’s celling is high is because of the conditions of the UK itself. I sometimes think Britain is secretly experiencing a big social science field experiment with the research question:

How long would it take for a country to elect a right-wing populist if we created the conditions most favourable to right-wing populism?

Extremely high living costs (especially housing and energy)

Wealth inequality

Frozen income tax thresholds dragging people into higher brackets

Record high immigration

An inability to stop illegal immigration

Literal daylight robbery being met with indifference by politicians and the police

Institutional failure leading to a decline in trust in parliament and the media

The main centre-right party failed in government

The main centre-left party failing in government

The main liberal party lead by someone who is more interested in making himself a meme

The main left-wing environmental party more interested in being a NIMBY party of protest

Ineffective ‘anti-populist’ campaigns ran by and for the Centrist-Dad-Podcast-Industrial-Complex-Alliance of Social Democrats and Tories.

If all of this continues to 2029, why wouldn’t Reform do well?

The biggest obstacle to Reform’s success might be Reform itself. Combustible egos at the top, organisational weakness, personal scandals and a general lack of professionalism could all undermine its ability to capitalise on voter discontent, giving wavering voters a reason to stay away.

3. For Labour, the margin between victory and defeat is small

We won’t know the full extent to which Labour are now in trouble until the next BESIP in May 2025, but there are a few things that can be said about their 2024 victory.

The first is that Starmer’s (or more probably Morgan McSweeney’s) unstated but fairly obvious strategy of ‘hippy punching’ (actively distancing Labour from the liberal-left) was a necessity in a first-past-the-post (FPTP) electoral system.

The New Left and Social Democrats are solid Labour supporters but were frequently isolated in their policy preferences compared to the rest of the population, particularly on immigration and Brexit. Catering to these segments would have pleased Labour’s base, but would have limited their electoral appeal to ideologically narrow and geographically concentrated groups.

By rejecting (or at least moderating) New Left and Social Democrat positions, Labour was able to win across a much broader range of voters, securing a majority despite a relatively low overall vote share. This is important under FPTP, where a party doesn’t need a huge percentage of the popular vote to win a majority. Labour’s victory was about appealing broadly to enough segments. This enabled the party to win across the country, maintaining its relevance even without a dominant performance in any one area.

They actually went slightly down with Social Democrats and were way down with the New Left compared to 2019.

The key to their victory was that they did better with every other group, with a swing towards them in all but Thatcherites. This might not seem like much, but under FPTP, success isn’t about winning by huge margins but about doing well enough with enough voters in enough seats. It is infinitely better to do just well enough with everyone than to do great with a couple of segments and terribly with all others.

However, this broad appeal also creates vulnerabilities in government. The party’s support was widespread but not deep – a ‘political sandcastle’ that is liable to be swept away. This means that even a modest shift in opinion will have a significant impact on Labour’s ability to retain power.

This is especially true because the 2024 election result left Britain with a huge number of marginal constituencies where a small swing would change the result of a lot of seats. This makes their hold on power very fragile.24

Early signs suggest that Labour are struggling with the same issues of competence that the Conservatives fell into. If Labour continues to struggle with implementation (trolleying from ‘pledges’ to ‘missions’ to ‘milestones’ without any coherence) it risks alienating those who were initially drawn to the party by the promise of change.

As well as this, the very clusters Labour had to distance itself from could now drift towards the Greens or Liberal Democrats, exacerbating their loses. In opposition, ‘hippy punching’ didn’t make too much of a difference to the New Left or Social Democrats, because they were united around the goal of ousting the Conservatives. However, if these voters perceive little difference in outcomes between a Labour and Conservative government, they might question why they should continue supporting Labour at all.

Despite these challenges, Labour doesn’t need a dramatic change in fortune to hold onto power. Given the state of current polling for the main parties, the party could very well still retain a majority with as little as 30% of the vote. With the Conservatives and Reform splitting the right, if Labour can secure a bit more than this, it could still win under the FPTP system.

4. Measuring efficacy and populism gives you more insights

Surveying just the economic and cultural dimensions provides a quick and useful snapshot of political attitudes. However, efficacy and populism adds a new layer of understanding, particularly if UK politics continues to fragment and dealign.

Take the Tories and the Thatcherites. On the surface, their policy views are quite similar, especially on the economy. In 2019 both overwhelming voted Conservative. And yet, in 2024, Tories were much less willing to defect to Reform compared to the Thatcherites.

One major difference between the two is that Tories have very low populism and very high political efficacy. In contrast, Thatcherites score high on populism, so are much more inclined to believe that the system is broken and needs to be shaken up.

Similarly, Social Democrats and the New Left are nearly identical on the social/cultural preference dimension, and still very similar on the economic one. However, in 2024, the New Left was much more likely to leave Labour for the Greens. Again, Social Democrats have very low populism and high efficacy, but the New Left, while not as anti-establishment as some other groups, is much more populist.

Another advantage is that it helps explain how people engage with politics. Political campaigns often focus on policy preferences to target voters, but someone with low efficacy and high populism will engage with politics in a fundamentally different way from someone with high efficacy and low populism.

For example, the Alienated were far less supportive of tax-and-spend policies than you would expect given their economic values. The Labour Party could be targeting them with messages about all the wonderful government spending and services they will provide if elected. But the Alienated have very low political efficacy, meaning they don’t trust the government to spend money in a way that benefits them.

Targeting the Alienated in such a conventional manner is completely detached from their reality. They don’t believe that more government intervention will help, because they fundamentally don’t believe politicians work in their interests. Any successful attempt to engage them would require an entirely different approach.25

Beyond elections, you might wonder how so many ex-politicians can set up a podcast together despite coming from opposing parties. The answer is that these people share the same underlying political temperament: very low populism and very high efficacy. Many of the prominent figures in political discourse (whether ex-politician, journalist or pundit) are clearly Social Democrats or Tories.26 This means they all agree on the value of compromise, procedural norms and institutional stability, and they naturally find common ground in their belief that politics should be conducted through established processes.

This also explains why these figures seem so incredulous at the public’s appetite for radical political change. To them, stability, compromise, and expertise are the foundation of good governance. However, for groups like the Alienated and the Old Left, leaders who promise to cut through bureaucracy and take decisive action, even (or especially) at the expense of the established order, are deeply appealing. These voters do not see the institutions that Social Democrats and Tories hold in such high regard as trustworthy or effective. Instead, they see them as obstacles that prevent meaningful change.

For me, this is also why ‘anti-populist’ movements often fail: the people leading them come from high-efficacy, low-populism segments. They do not share the deep dissatisfaction voters feel towards institutions, so they end up misdiagnosing the cause of discontent (e.g. ‘misinformation’) offer solutions which are completely emotionally unintelligent (e.g. ‘I, your social superior, will run expert-designed policy through our cherished established institutions and these will benevolently make your life better’), or treat voters as stupid (e.g. ‘Yeah, you say you want lower immigration but I know what you actually want are potholes filled in’). In doing so, they only reinforce the divide they want to bridge.

There is also a more well-meaning version of high-efficacy low-populism: the idea that institutions should be defended because they exist to protect the people who need them most. The irony is that the very groups who are supposedly benefiting most from institutions (low incomes, working-class occupations, the least political power) are the ones who distrust them the most. The Alienated, the Disengaged, and the Old Left were the most economically precarious segments of the electorate, yet they also have the highest levels of populism and/or the lowest efficacy. If these institutions truly existed to serve them, this is a funny way of showing gratitude.

I’ve often wondered if one overlooked reason why Thatcher was more successful with working- and especially lower-middle-class voters than you’d expect was because she was fundamentally an anti-paternalist. She did not frame her approach as an act of benevolence from a social superior towards the less fortunate. Instead, her message was: ‘Only you can sort your life out. Government can’t, won’t, hasn’t before, and never will.’

This approach is much more suited to the temperament (and life experiences) of a low efficacy voter compared to well-intentioned but patronising do-gooder rhetoric of state-led uplift in which voters are the passive recipients of help. To a low efficacy voter, ‘I’m not going to do anything for (and, therefore, to) you’ provides far more agency than a message of ‘I am your educated better and I’m going to do things to you for your own good.’

This is why warnings that Reform is ‘too economically right-wing’ to appeal to certain segments is (literally) one-dimensional thinking. A message of ‘getting the government off your back’ doesn’t just have a material appeal to those on a high income. It also appeals to low efficacy voters who have a negative perception (and experience) of government action being done to them.

5. Need for the next wave of the BESIP

The next wave of BESIP data in May 2025 will be fascinating. Tracking public perceptions of competence will be particularly crucial. If Labour starts to suffer from the same credibility gap that doomed the Conservatives, it could find itself in big trouble.

Equally important will be any shifts in policy preferences. Under thermostatic opinion, public opinion often reacts against the ideology of the ruling party. In this case, after a year of Labour in government, we might see a shift in public sentiment in an anti-left and/or anti-liberal direction. While this might not happen immediately, the public could start to shift in their views, especially on issues like immigration or taxation.

Until we know, British politics remains as unpredictable as ever.

Watch this space 👀

In academia, the terms that are used are ‘Libertarian’ and ‘Authoritarian.’ Using the term libertarian is confusing because in popular political conversation it means someone who is both economically right-wing and socially liberal, whereas in academia it means someone who is socially liberal regardless of their economic opinion.

Using the term authoritarian to describe social conservatism is also inappropriate. Authoritarianism is (and as a term should only be used to describe) a non-democratic government regime and people who have anti-democratic beliefs. Some people who are socially conservative support dictatorships, sure, but the overwhelming majority in the UK don’t – and some socially liberal people can come across as being happy to ignore democratic votes if it suits their cause.

It says a lot about academics that they will happily and unthinkingly use – without recognising or acknowledging the immense amount of political bias this displays – the same term for Mussolini that they do for someone who thinks immigration is too high.

Wave 27

The questions for each dimension were all 5-point ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’ on the statements:

Economic

Government should redistribute income from the better off to those who are less well off

Big business takes advantage of ordinary people

Ordinary working people do not get their fair share of the nation’s wealth

There is one law for the rich and one for the poor

Management will always try to get the better of employees if it gets the chance

Cultural

Young people today don’t have enough respect for traditional British values

For some crimes, the death penalty is the most appropriate sentence

Schools should teach children to obey authority

Censorship of films and magazines is necessary to uphold moral standards

People who break the law should be given stiffer sentences

Efficacy

I have a pretty good understanding of the important political issues facing our country

It takes too much time and effort to be active in politics and public affairs

Politicians don’t care what people like me think

People who vote for small parties are throwing away their vote

It doesn’t matter which political party is in power

Populism

The politicians in the UK Parliament need to follow the will of the people

The people, and not politicians, should make our most important policy decisions.

I would rather be represented by a citizen than by a specialized politician

Elected officials talk too much and take too little action

What people call “compromise” in politics is really just selling out on one’s principles

Graded response model

Elbow method

K-means clustering used

Because the vote intention question was based on answers before the election, I re-weighted the data based on the actual result. I also re-weighted (using raking) on age, gender, education, region and ethnicity, because the BESIP tends to (massively) underweight people who don’t vote or don’t have a degree:

Age

18-24: 10.6%

25-34: 16.9%

35-44: 16.5%

45-54: 16.9%

55-64: 15.8%

65-74: 12.5%

75+: 10.8%

Gender

Male: 48.9%

Female: 51.1%

Education

Below degree: 66%

Degree: 34%

Ethnicity

White: 84.9%

Asian: 8.1%

Black: 3.4%

Mixed: 1.8%

Other: 1.8%

Region

East of England: 9.6%

Greater London: 13.4%

North East: 4.1%

North West: 11.4%

Scotland: 8.3%

South East: 14.2%

South West: 9%

Wales: 4.8%

West Midlands: 9.1%

Yorkshire and the Humber: 8.5%

Vote Intention

Labour: 20.22%

Conservative: 14.22%

Reform UK: 8.58%

Lib Dem: 7.32%

Green: 3.84%

Other or Independent: 3.9%

SNP: 1.5%

Plaid Cymru: 0.42%

Not Vote: 40%

Here is what occupation looks like showing the within occupation make-up (eg 31% of people who work in routine occupations are Alienated). This is takes into account each cluster’s percentage of the overall population, meaning groups like Disengaged, Libertarians and Middle have quite high numbers in all occupations, given there are so many of them in the population as a whole.

For a very interesting and entertaining book that looks in-depth on the lower-middle class in the UK, I strongly recommend Dan Evans’ book A Nation of Shopkeepers.

The original question used a 0 to 10 scale, but I changed it to -5 to +5 because it makes more sense visually.

Because this was an open-ended question, people can write whatever they want, but answers tend to be pretty similar. I used to manually code these responses for the BESIP and I can assure you that people’s answers provide an unfiltered and unadulterated glimpse into the British electorate’s psyche.

By ‘centrist’ and ‘moderate’, I mean actual moderate centrists (i.e. people’s who’s preferences are about average compared to the rest of the population). I do not mean podcasters and newspaper opinion columnists who go about calling themselves ‘moderate centrists’. The views of people like this (free markets, free trade, free movement of people, and free love) are the complete opposite of where public opinion is.

Halving inflation, growing the economy, reducing debt, cutting NHS waiting lists, and stopping the boats

In the face of failure, they would blame civil service obstructionism. To be fair, I’m sure that the civil service was incompetent (and insubordinate) and that this was very frustrating for ministers. However, after 14 years, all this shows is a complete failure to institute reforms to improve the bureaucracy’s performance and responsiveness. Voters were not going to give you sympathy for an inability to master the levers of government after well over a decade in power.

Given that groups like this are so hard to reach for pollsters, if Reform can make gains here it would likely be missed in the run up to an election. If Reform can replicate Trump’s mobilisation strategy and find innovative ways to increase turnout, it could potentially flip seats that people are not currently expecting.

Figures such as Peter Hitchens, Munira Mirza and Claire Fox have all made this transition in their own political lives.

And if they do, even if this group is very small, their experience in grassroots campaigning, strategy, and direct engagement with voters could end up providing a boost to Reform’s infrastructure.

Like a Ming Vase, you might say

Such as…

For academics, use the rule of thumb:

Junior academic = New Left

Senior academic = Social Democrat

Why is that traitor a thing?

Oh… he’s a billionaire’s butt plug.

Top-quality stuff. Really well researched and presented in a straightforward and compelling manner.