The Next Big Political Divide Might Be Hiding in Plain Sight

A closer look at how the dry kindling of overlooked issues could ignite to reshape the political landscape

Hello there! 😀

This is a write up of one of my academic articles about what issues are out there in public opinion that voters want and care about, but which political elites are not supplying.

If you want to read the boring, dull, stodgy, stuffy, tedious, tiresome academic version of the article, you can access it here: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5087665

But if you want to read the same findings in a (hopefully) more accessible and entertaining way (including how a 1999 Backstreet Boys album helps explain the electoral appeal of Nigel Farage) read on here.

There’s a cliché in British politics that what the average voter wants is to fund the NHS and hang the paedos.

Politicians always (rhetorically) supply one of these. Every party makes a point of promising more money for the NHS and you can’t get elected if you don’t. Let’s not get into whether they actually deliver this, but the promise is always there.

However, the death penalty is treated very differently. Even Nigel Farage doesn’t support it. And those who’ve flirted with it before, like Priti Patel, walk back their support if they want to climb the ministerial ladder.

But this isn’t just about the death penalty. There are many issues that get support from the public but are ignored by politicians. Sometimes these are on the left, sometimes on the right. Sometimes they’re new or different and don’t fit neatly into existing political ideologies.

So I wanted to find out:

What are the issues that people care about that no major party is seriously talking about?

And if a party did take a clear position on one of those issues, would it actually change how people vote?

I Don’t Want It That Way

The idea started with a book I read on the media industry. In Media Disrupted, Amanda Lotz explains how the internet shook up music, newspapers, film and TV. It’s not a book about politics but while reading it, I couldn’t help noticing the parallels.

Borrowing from Bharat Anand, Lotz uses the metaphor of dry kindling to show how consumer dissatisfaction in these industries built up over time.1 When companies kept offering things people didn’t really want, frustration grew. That frustration didn’t cause immediate change, but it created the conditions that made people willing to go to an alternative when a spark (the internet) finally came along.2

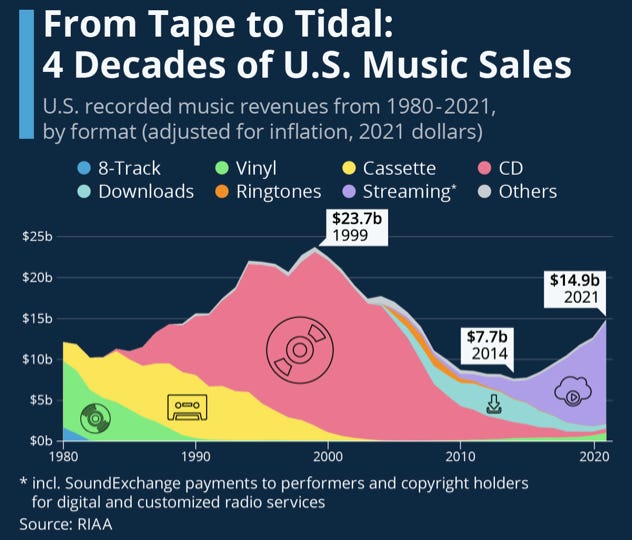

Take the music industry in the late 1990s when the CD format was at its peak.

The industry was actively using underhand tactics to get people to not buy singles. Instead, they pushed them to (the much more profitable for them, much more expensive for you) albums, even if people only wanted one or two songs on that album. It was frustrating for music fans and that frustration built up over time. Every annoyed, ripped-off customer was another piece of dry kindling.

But, in 1999, things were fantastic for music executives. The music industry was making huge profits and it looked like the good times would never end.

One of the biggest albums that year was Millennium by the Backstreet Boys. The first three tracks (Larger Than Life, I Want It That Way, Show Me the Meaning of Being Lonely) are classics of late-90s pop. Millions of people bought the album because of those three songs.

But after that, like most CDs from that era, it was mostly filler. If it’d been around back then, people would have wondered if they had been written by ChatGPT. People had to pay £15+ in 1999 prices (that’s £25+ today) for the couple of songs that they actually wanted.

The Backstreet Boys were not the only ones doing it. Go and have a look and a listen to some of the later tracks on 1990s albums. It’s mostly rubbish, despite the opening songs being bangers. Yet, people had to pay the full album price for those select number of songs.

Consumers weren’t getting what they wanted, but were stuck with what the industry gave them. Sales looked great, but it was a false signal. People didn’t love the CD model, they just had no other choice. That was the dry kindling.

And then came the spark.

With legitimate sources not offering what people wanted, they turned to less reputable ones. The internet would have disrupted the music industry regardless, but if they’d given people what they wanted, the appeal of Napster, LimeWire and Pirate Bay would have been much smaller.3

Eventually, the industry caught up, but it was too late to stop the damage. Music revenue collapsed after 1999, and it’s only just beginning to recover.

The message of all this is that demand doesn’t always lead to supply, and what’s being supplied isn’t always what people want. Just because people are buying from the incumbent doesn’t mean they’re happy. The moment something better comes along, everything can change.

Me and My Heart, We Got Issues of High Potential

Writing in the 1970s, David Butler and Donald Stokes described how public opinion can form around an issue even when the main parties ignore it.

They gave the example of immigration in the 1960s. Even though Labour and the Conservatives weren’t really talking about it, ordinary voters were.

The explosive possibilities of the issues raised by coloured immigration were only partially recognized during the early 1960s. Yet the question was very salient to the mass of the people… immigration was spontaneously mentioned in 1963 by a substantial number of our respondents, even though it was then playing a relatively small role in public debate. Moreover, a specific question about immigration elicited fewer ‘don’t knows’ than any other issue question in our survey, except for one about the importance of the Queen and Royal Family. Indeed, a remarkable proportion of our respondents – fully a quarter – felt strongly enough to go beyond the ‘closed’ question and to offer spontaneous elaborations of their hostility to coloured immigration. In 1964, 1966 and 1970 we found that half our sample felt ‘very strongly’ about immigration and a further third felt ‘fairly strongly’.

This was an ‘issue of high potential.’

Bottom-up demand from a large proportion of voters.

Limited or absent elite responsiveness.

Potential to significantly influence vote choice if political elites took a stance.

But if people care about something, and a party could gain votes by talking about it, why don’t they?

‘Issue ownership theory’ argues that parties don’t just chase votes on any topic. They focus on issues where they’re already seen as strong and trusted. They avoid issues that divide their own voters or where they’re seen as weak. Even if an issue is popular, a party may stay quiet if talking about it risks upsetting its base or opening up a fight it might lose.

Sometimes, ignoring the issue can keep an issue off the political and media agenda. If neither side wants to talk about it, it can stay dormant.

But like a volcano, one day it might erupt.

That’s where ‘political entrepreneurs’ come in. These are parties or leaders who identify issues that people care about but that the big parties avoid. They then use those issues to set themselves apart. Catherine De Vries and Sara Hobolt describe them as disruptors, like start-ups in the business world.

Crucially, they don’t just compete on the same old topics. They bring in new dividing lines that cut across the old party system, meaning they can win voters from different parties. These voters may not agree on everything, but they share a frustration with the thing the main parties are ignoring.

By doing this, political entrepreneurs carve out a unique appeal. They don’t have to beat the mainstream parties at their own game. Instead, they shift the conversation to new ground that the big parties have chosen not to fight on.

But how do we know what the big unmet demands are right now? The challenge is that most survey methods weren’t designed for this. Surveys can show gaps between what voters want and what politicians do, but they don’t tell us if voters care enough about it to change their vote. How do you even select which issues to poll? By their nature, unmet demands are hard to spot. If they were obvious, they’d already be getting attention.

In this project, I created a new method to spot ‘issues of high potential’ before they break into mainstream politics. If you want an exhaustive explanation and justification of my methodology, please read the academic version of this article. Here, I’ll just give a quick overview of the methods and focus mainly on the results.

I'll Tell You What I Want, What I Really, Really Want

To see where the genuine bottom-up demand was, I first ran survey in October 2023 in Britain that asked people to name a policy or law that they felt elites were neglecting that they wanted to see put into effect. What made this survey distinctive was that respondents weren’t forced to choose from a list. Instead, they could type whatever they wanted without being primed, nudged or constrained by pre-defined options.

Each answer was coded into two groups:

The specific policy a respondent asked for (e.g. ‘Bring back the death penalty’ or ‘More police on the streets’).

The broader group that these policies fall into (e.g. ‘Tough on crime’).

This shows the ten most common broad positions. The leading category was ‘Tough on crime’ (11.3%), followed closely by ‘Restrictive immigration/asylum’ (11.2%). ‘Do More on Climate/Environment’ (8.2%) came in third. There was then a drop-off after this to areas like transport reform (5.8%), healthcare (4.8%) and education (4.2%).

Looking at the specific policies that were brought up, no single one dominated. The most commonly mentioned policy (no prizes for guessing) was support for the death penalty. However, it was raised by just 3.3% of respondents.

Many of the top policies were socially conservative. Alongside the death penalty were demands for tougher prison sentences (2.1%), deporting illegal immigrants (1.9%), and limiting legal immigration (1.8%).

At the same time, there was a meaningful presence of liberal-leaning priorities too. Calls for greater climate action (2.4%) and cannabis decriminalisation (1.2%) were among the more frequently mentioned policies.

And there were a number of responses that fell outside clear ideological categories. Being against vaping (1.5%) and wanting to introduce dog/pet licences (0.9%) aren’t positions that easily map onto traditional left–right or liberal–conservative axes.

The key takeaway is that people want lots of different things, many of them not represented by mainstream parties. It’s a landscape of diverse preferences, many of which are unclaimed, and unactivated.

A Hansard Day’s Night

However, clearly not all of the issues named here were actually being ignored by British political elites. To identify truly dormant policies, I focused on the 50 most commonly suggested specific proposals and checked how often each was mentioned in Hansard (the official parliamentary record) over the past year. Only the policies mentioned least in Parliament were kept and classed as unactivated.

After doing this, the following 10 ‘unactivated’ policies met the criteria:

Convicted paedophiles should be given the death penalty.

The UK should have no immigration whatsoever for the next 5 years.

The percentage of seats a party wins in a general election should be the same as the percentage of votes they get nationwide.

Cannabis should be legal to use, buy and sell.

The UK should re-join the European Union.

It should be illegal for landlords to raise rents by more than the rate of inflation.

People should have to get a licence in order to own certain breeds of dog.

Every British citizen should receive £500 per month from the government with no strings attached.

It should be a crime for MPs to knowingly mislead Parliament.

Assisted dying should be legal for people with a terminal illness.

An eclectic mix, I’m sure you’ll agree! And yes, I know that assisted dying has since become a much bigger issue in politics, but it wasn’t at the time of this research.

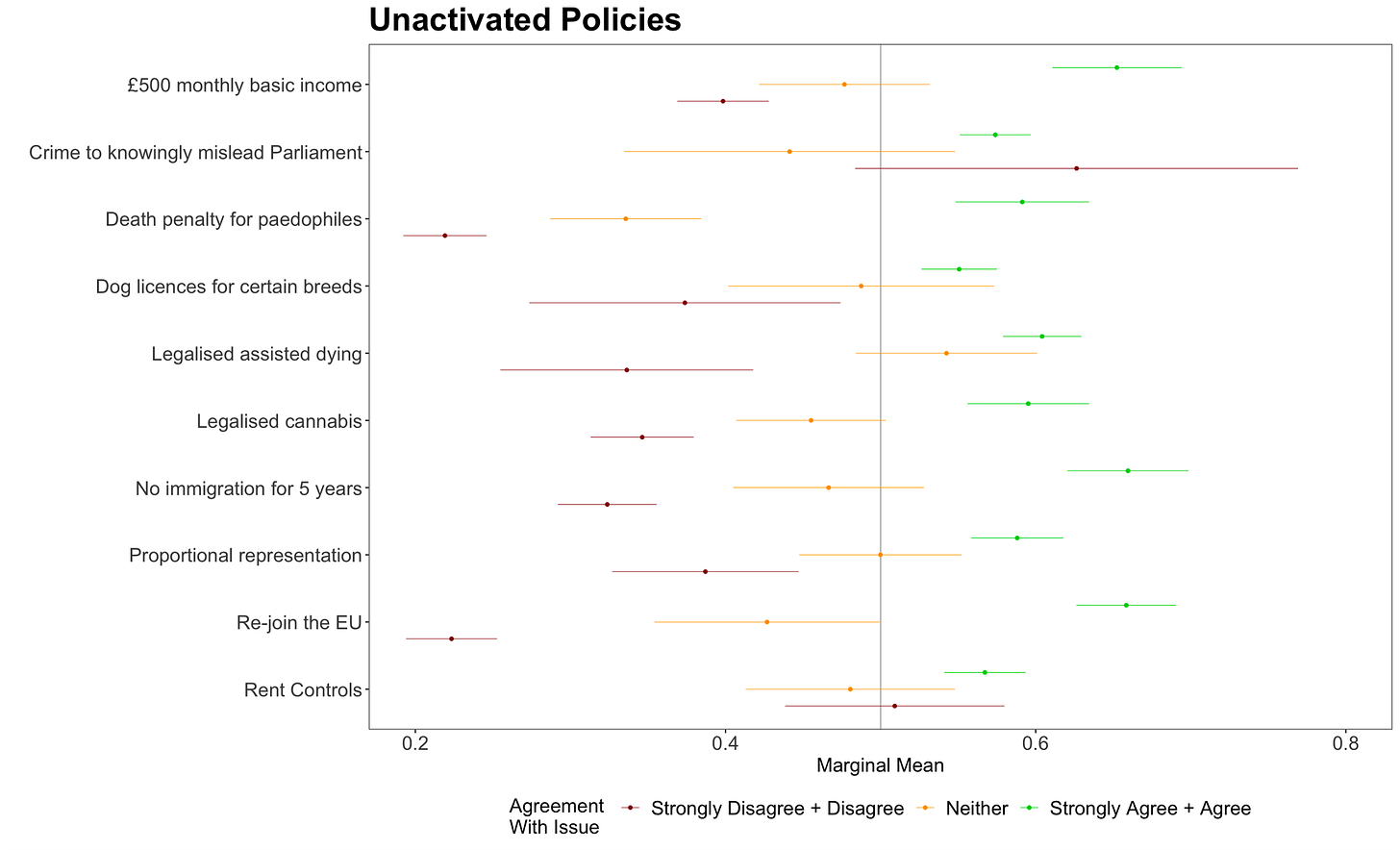

When I polled the final ten policies, criminalising misleading Parliament received overwhelming agreement. Legalising assisted dying, rent controls and dog licensing also elicited clear support. However, issues like the death penalty, strong restrictions on immigration and legalising cannabis triggered more polarised responses. Rejoining the EU was particularly divisive. The proposal for a Universal Basic Income (UBI) also saw more opposition than support.

What matters, though, isn’t just which policies are popular or unpopular, but how they perform compared to what people were actually being offered at the time.

Both the Conservative and Labour parties held their annual conferences in the same month as the open-text survey. These ended in set-piece speeches by the party leader where they outlined their vision on their own terms.

So I took the five key proposals from Rishi Sunak’s 2023 conference speech and the five from Keir Starmer’s, treating them as the best available proxy for ‘activated’ policies that elites were focusing on.

Offer tax-free bonuses to teachers of key subjects to attract and keep them in the job.

If someone is convicted of murder, they should be given a whole-life prison sentence with no chance of release.

Cancel the HS2 high-speed rail project and reinvest the funds into local transport.

Replace A-Levels and T-Levels with a new qualification that has more subjects, more teaching hours, and compulsory English and maths.

Ban the sale of cigarettes to people born after the year 2009.

Create a government-owned energy company to increase renewable energy production.

Create new technical colleges with links to local economies and job markets.

Increase NHS spending to reduce backlogs.

Build 1.5 million more homes across the country.

Zero hours contracts should be banned

I don’t know about you, but what was striking when doing this study was how uninspiring these offerings were. It’s not that the ideas were unpopular. In fact, they were largely well-received, which suggests some decent polling and focus-grouping had been done. However, they were also remarkably meh. The contrast with some of the high-potential issues (bolder, more divisive, but also more energising) was stark.

Choose Life, Choose a Job, Choose a Career, Choose Dog Licences

To test the relative importance of high-potential issues, I fielded a vote choice conjoint experiment in May 2024.

A conjoint experiment is a survey method used to understand how people make trade-offs between different choices. Instead of asking people how much they like a policy in isolation, it places them in a decision-making scenario: choosing between two hypothetical candidates, each offering a bundle of policies (a mixture of the 20 outlined above). This means conjoint analysis reveals which issues genuinely sway people when stacked up alongside others.

I framed the conjoint as a leadership contest within either the Labour Party or the Conservative Party, where the party that people saw was based on who they said they preferred out of the two. Each respondent was presented with two candidates, each with a randomly generated four-policy platform.

In my analysis, I look at something called marginal means. This is the proportion of people who voted for a candidate backing a policy. A score of 1 means everyone voted for the policy, while a score of 0 means no one did. Anything above 0.5 means it was mostly voted for, while anything below 0.5 means it was mostly voted against.

Standing in the Way of Rent Control

First, I looked at how policies influenced vote choice depending on whether someone agreed or disagreed with them. For example, if people who agreed with Policy X had a marginal mean of 0.62, that means 62% of them voted for a candidate who supported it.

Both activated and unactivated issues influenced vote choice, showing that even when politicians ignore certain topics, voters still care about them.

Unactivated policies often had a bigger impact. Four of the five policies most strongly voted for by agreeing voters were unactivated: no immigration for five years, rejoining the EU, UBI, and assisted dying. Only NHS backlog funding from the activated list made the top five, confirming the NHS’s enduring appeal.

Opposition was also sharper for unactivated policies. The most strongly voted against by disagreeing voters included the death penalty for paedophiles, rejoining the EU, no immigration for five years, assisted dying and cannabis legalisation.

Unactivated policies were both more divisive and more motivating. The biggest gaps between those who agreed and disagreed were all unactivated: rejoining the EU (0.44), death penalty for paedophiles (0.37) and no immigration for five years (0.34).

However, disagreement tended to have a stronger effect than agreement (with scores further from 0.5). For rejoining the EU, those who disagreed had a score of 0.22 (far from 0.5) while those who agreed had a score of 0.66 (closer to 0.5). A similar situation occurred with the death penalty, where those who disagreed had a much lower score (0.22) compared to those who agreed (0.59).

Bring It All Back to EU

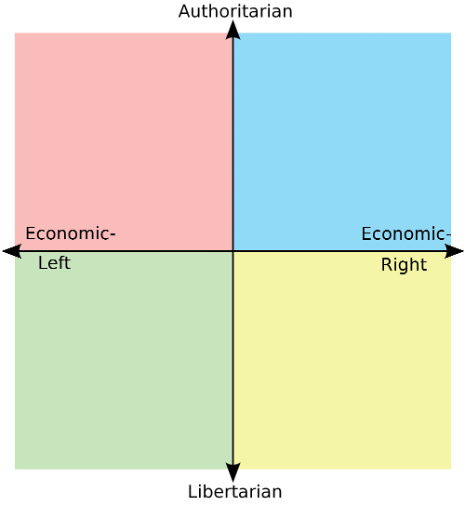

The theorised importance of issues of high potential is that they can create new political alignments. To explore this, I looked at how people’s responses matched up with their broader political values.

I used the left-right economic scale and the libertarian-authoritarian social scale included in the BESIP, which have been shown to be good estimations of preferences on the economic and non-economic dimensions in the UK. These help us understand a person’s underlying political values, which are often more stable than their party preference.

To assess the relative importance of issues, I looked at the significant policies that had the biggest impact on people’s votes (i.e. those with scores furthest from 0.5). This gives a good sense of what issues matter most to different groups.

Unactivated issues turned out to be a stronger motivator of vote choice than activated ones. For example, unactivated policies made up 5 out of 7 top issues for Left-Traditionalists, 6 out of 8 for Right-Traditionalists, and 6 out of 7 for Right-Libertarians. Left-Libertarians had an even split, but all of their top four issues were unactivated.

Some issues divided voters. Rejoining the EU had the biggest effect on Left-Traditionalists and Right-Traditionalists who opposed it, but was also strongly supported by Left-Libertarians. Similarly, banning immigration for five years was a big motivator for Right-Traditionalists who backed it, but also for the Libertarian groups who both opposed it.

Certain policies had very different effects depending on the group. The death penalty was strongly opposed and proportional representation was supported by the Libertarian groups, but had little impact on the Traditionalist groups. In contrast, legalised cannabis was opposed by Traditionalists but barely moved Libertarians.

A few issues united voters. Making it a crime to knowingly mislead Parliament was popular across all groups, though not a top priority. Increasing NHS backlog spending was widely supported and ranked highly across the board.

Through the LimeWire

So, are these are the issues to redefine politics? I don’t know. I’ll be honest, this whole process isn’t perfect and has problems (see the academic version for a discussion).

I’d take these results seriously but not literally. By that, I mean I was able to show that people have demands that aren’t being responded to by politicians, and these can have an effect on vote choice that is bigger than policies that were getting talked about. However, whether or not the specific issues uncovered here are the most effective ones to win votes is open for debate and needs a lot more testing.

The key takeaway is that voters can identify and articulate areas where politicians are neglecting their demands. The fact that these issues had a strong effect in the conjoint experiment suggests that public opinion can exist independently of what political elites are blabbing on about.

I think that Lotz’s ‘dry kindling’ analogy is a really useful one. It helps clarify how and why political change can happen. When enough unmet demands quietly build up, it can only take a spark to set everything moving.

Think about politics in the 2000s. The major parties had a cosy consensus on a lot of issues, particularly immigration. Surveys consistently showed how much it mattered to voters and how strongly they wanted it reduced. However, the main parties didn’t want to talk about it, or couldn’t do anything because of EU free movement, or were divided internally, or were scared of being labelled racist.

Elites not talking about the issue didn’t mean the demand for lower immigration disappeared. The frustration just built up like a lot of dry kindling.

And then came the spark.

Nigel Farage and music piracy broke all the rules, were impossible to ignore and caused havoc for the established players who panicked and scrambled to respond.

The mainstream didn’t give people what they wanted. When supply didn’t meet demand, people went looking for alternatives. Like Pirate Bay, there’s a chance Farage might break the family computer, but there’s also a chance you’ll get what you want.

And dry kindling doesn’t just exist on immigration.

Take Labour in Scotland before the 2014 referendum. For years, Scottish voters had grown frustrated that their MPs seemed more focused on London, felt taken for granted and were disappointed with the party’s direction. The 2014 independence referendum was the spark that lit all that built-up anger, leading to a mass exodus to the SNP in 2015.4

We may have seen a similar pattern with Muslim Labour voters in 2024. Gaza was the spark, but reports suggested that Muslim voters had long been dissatisfied with Labour, despite continuing to vote for the party in large numbers.5 Just looking at the past vote share would have given a misleading picture of what people really thought. The dry kindling was already there and Gaza simply ignited it, leading to the success of independent candidates.

That’s the power of long-term unmet demand. It often goes unnoticed, building slowly in the background, until, suddenly, it bursts into the open. That’s when you get the political surprises that leave everyone wondering how they didn’t see it coming.

You Think That You're the Man / I Think, Therefore, I Am

IT DOESN’T MATTER WHAT YOU THINK!

What really matters is what you care about.

To understand public opinion, knowing someone’s agree/disagree opinion isn’t enough. You also need to know how much they care about it compared to everything else.

Just because someone agrees or disagrees with a policy doesn’t mean it will shape how they vote. Sometimes, agreement drives vote choice by attracting them to a party. Other times, disagreement turns someone off a party advocating something. Most of the time, neither moves the dial.

Traditional polling has struggled with this. Usually, something gets polled and if more people agree it’s seen as a vote-winner, and if more people disagree it’s seen as a vote-loser. But this is one-dimensional thinking.

The other problem is that asking survey respondents to rate how ‘important’ an issue is to them doesn’t have a good track record at telling us how they actually prioritise it when faced with real trade-offs. That’s why we need better tools that capture relative importance, which my experiment was designed to try and do.

You can see the gap between popularity and priority in election campaigns. Labour’s 2015 effort was (correctly) derided by David Axelrod as the ‘vote Labour and win a microwave’ campaign. They offered lots of individually popular policies, but completely missed what voters actually cared about: leadership and the economy.

Compare that to the Conservatives in 2019. ‘Get Brexit Done’ worked because it was a clear message that matched what the public thought and cared about. Meanwhile, Labour’s offer was again full of crowd-pleasers (free broadband, nationalised rail), but those issues were nowhere near the top of people’s priority list like Brexit.

This mistake isn’t just made by political parties. You see it all the time in campaign group polling. A group will commission a survey, ask a question that (surprise!) shows most people agree with them, and then release a headline that politicians must ‘listen and act or lose votes.’ But even if the poll is totally fair and well-worded (it almost always isn’t), agreement doesn’t mean votes will shift.

Next time you see a poll on an agree-disagree scale, you should shrug. It doesn’t mean much on its own. Ask yourself instead: how does this issue likely compare to how much people care about the NHS? Or the economy? Or immigration? The answer will almost certainly be that it doesn’t even come close.

Knowing about what people care about can also challenge some of the clichés in politics. Take the meme from that the start that what people want is to ‘fund the NHS and hang the paedos.’

I found that people really did agree with more NHS funding and it was a major vote-driver, because people prioritised it above other issues.

But hanging paedophiles? In my experiment, people against the death penalty were far more motivated by the issue than those in favour. Just looking at a simple agree/disagree poll would have made it seem like the issue was evenly polarising, but only one side actually cared – and it wasn’t the side pushing to bring it back.

It’s the same with rejoining the EU. Simple agree-disagree polls often show a majority for rejoining, which gets a lot of people on Bluesky excited. Again, though, that doesn’t mean it’s a vote-winner. In my data, anti-rejoin respondents voted against it much more strongly than pro-rejoin respondents vote for it.

If anything, it wasn’t hang the paedos, it was hang the politicians that united respondents. I don’t think it needed to be banning lying in Parliament specifically (though that’s not exactly unpopular). It could be proposals like cutting MP pay, enforcing term limits or other moves to show politicians are being held to account (or punished). I doubt the exact policy mattered as much as the target.

Love on Top

One debate in political science that my study tried to explore is whether public opinion is shaped top-down (meaning politicians, media and other elites set the agenda, and the average voters follows their lead) or bottom-up (meaning voters have independent preferences that emerge from their own lives and experiences, which politicians have to respond to).

My own view is that it’s inevitably a bit of both. Political divisions aren’t just manufactured and they’re not just organic. They’re almost certainly the result of an ongoing interplay with different feedback mechanisms.

Politicians have a lot of ability to control the narrative and can strategically emphasise certain issues to win votes. However, it’s very hard to invent divisions out of nothing. If there’s no underlying tension, people usually won’t care.

At the same time, just because societal disagreements exist doesn’t guarantee politicians will be able to exploit them. Some fault lines stay dormant for decades, some never fully ignite, but some are strike a chord straight away.

I found that voters care about more than just what political elites tell them to. People were able to articulate clear demands that weren’t being talked about by the political class. This challenges the idea that voters are just passive sponges soaking up elite cues. However, we shouldn’t pretend political elites can’t succeed in shaping opinion. Campaigning is all about making advantageous issues salient to win votes. If a party spots an issue where their supporters are united but the opposition’s supporters are divided, they’d be foolish not to use it as a wedge.

One political bias I see all the time (but which I don’t think has been give a specific name) is thinking this:

All the political opinions, trends and changes I agree with are the product of organic, bottom-up public demand.

All the ones I disagree with are the result of top-down elite manipulation.

It feels nice to think that everything you support is the genuine public demand and everything you oppose is imposed by elites, but it’s very unlikely that this is the case. Not everything you like is from the grassroots and not everything you dislike has been ‘astroturfed’ into existence.

You see this dynamic in the culture wars all the time:

From the ‘woke’, you’ll hear something like: “Ordinary people just want to get along! Elites create culture wars to divide us and distract from economic injustice!”

From the ‘anti-woke’, it’s often: “Ordinary people have sensible, common sense beliefs! It’s the elites in the media and universities that are imposing extreme cultural ideas on everyone else!”

Both fall into the same trap of assuming their side is organic and the other side is artificial. However, all of these things can be true at once:

People generally want to live and let live if given the chance.

Influential cultural institutions would really like ‘wokeness’ to become entrenched in society and law.

A lot of ‘woke’ cultural changes and ideas are genuinely unpopular with the public.

Right-wing politicians see this unpopularity and use it to rally working-class support.

None of these contradict each other. It’s just the mistake of thinking your team is always driven by popular demand and the other team is always top-down manipulation.

This isn’t just a culture war thing, it’s a broader political instinct. It shows a lack of curiosity and it’s no surprise that certain politics kept losing after 2016 when they retreated into comforting stories rather than understanding their opponents’ appeal.

Listen to Your Voters, Before They Tell You Goodbye

In a previous post, I made the case for not caricaturing and stereotyping voters.

I’d like to now make the case for actually listening to voters and taking them seriously.

By this, I don’t mean the way politicians always say they are ‘listening’ while ignoring the clear signals voters are sending them. Instead, I mean genuinely seeing voters as a source of collective intelligence and seeing this wisdom of crowds as a big strength of democracy.

One of the things I’ve always found strange about academia is how many people have chosen to spend their lives studying the public’s opinion while seemingly disdaining the public’s opinion. This isn’t about disagreeing with what the public thinks. There are plenty of popular ideas I think would be terrible if implemented. What I’m talking about is a deeper attitude where the public is fundamentally uninformed, inherently prone to believing falsehoods, and shouldn’t really be taken seriously.

Not only is that worldview anti-democratic, it’s also wrong.

One common claim is that the average voter is more vulnerable to ‘misinformation’ and needs elite guardians to protect them from bad ideas. Motivated reasoning is a natural human inclination that we are all (you and me included) prone to. But the literature in psychology shows that it’s the most politically engaged, formally educated people (e.g. you and me) who are most prone to filtering information through their pre-existing beliefs.

They consume more news and follow political debates closely. Crucially, this means they are better at rationalising away inconvenient facts. Instead of changing their minds when faced with conflicting evidence, they are the ones most likely to find ways to reinterpret the information so it fits what they already believe.6

‘Misinformation’ journalism and fact-checking have their place, but they’re needed far more for the highly educated, politically engaged crowd than for the average voter.

Brexit and Trump melted a lot of people’s brains, but one of the worst side effects is that defending the assumptions about voters that underpin democracy is now seen as (God forbid) ‘populist’ 😱😱😱.

But taking voters seriously doesn’t mean romanticising them. It just means recognising that, in aggregate, people often have a better sense of what’s wrong and what needs fixing than the people who spend their lives inside political bubbles.

My study showed that when you really listen, voters can articulate demands that aren’t being met by the political system. These demands aren’t random and they aren’t just reactions to what politicians are already talking about.

Ignoring voters comes at a cost. Long-standing frustrations, if left unaddressed, slowly pile up. You might not notice the discontent at first, but that dry kindling builds quietly, over time. The warning signs are easy to miss if (like the 1999 music industry) you’re only hearing what you want to hear. Listening properly is one of the few ways to spot where dry kindling is gathering before it catches fire.

This is also related to a quote from Chairman Mao that “a single spark can start a prairie fire.”

Here is Lotz’s explanation of the dry kindling metaphor:

In his book exploring strategies for digital change, Harvard Business School professor Bharat Anand argues that analysts often err in focusing their energy on exploring the cause of disruption and on identifying errors in its initial handing. Anand advocates instead for investigating the underlying conditions that lead change to be swift and extensive once triggered. He builds this argument through the metaphor of a wildfire, explaining that rather than debating whether a fire’s cause was a lightning strike, a tossed cigarette, or an uncontained campfire, the larger lessons for those who want to be prepared for, or prevent disruption, come from identifying the kindling that leads the fire to spread.

Every industry has different kindling, which is part of the reason that claims about the role of the internet in disrupting industries tend to be inadequate. In the music industry, the high price at which CDs were introduced and maintained by the industry provided considerable kindling. Additional tinder came from the industry’s insistence on selling albums rather than singles, and then from the industry’s delay in creating a legitimate marketplace for digital files. The recording industry did not respond to the fire on the scale required until unauthorized file sharing became abundant and threatened the foundations of the industry. In the case of ride sharing, the kindling was the difficulty of getting taxis in certain areas, of not knowing the financial commitment of the ride, and of high prices that derived from the systems municipalities used to license taxi drivers that effectively limited supply.

Businesses can thrive with substantial kindling, so long as there is no threat of a competitor or an adjacent sector igniting it. Internet communication introduced capabilities that were previously infeasible, and in many cases, unimaginable. This technological innovation effectively ignited kindling in many industries that delivered a suboptimal consumer product or experience because the previous state of technology enabled such underperformance.

Every industry substantially disrupted by the internet had kindling, although it may not have been perceived as such before the advent of internet communication and the new and enhanced capabilities it offered. Executives in these industries likely slept soundly at night, confident that their strategies were well matched to the existing playing field set by a combination of known technology, regulation, established business practice, and consumer desires. Others might have had more sleepless nights, aware that their strategy relied heavily on the playing field of the moment and that their strategies may be allowing them to maximize profit under these conditions, but that they were serving their investors more than meeting the needs and desires of their customers. Their businesses were tinderboxes, fine for now, but ill-prepared for a spark of change.

Another interesting book on a similar topic is Alan Payne’ Built to Fail about Blockbuster Video’s collapse. While many think Blockbuster’s failure was an inevitable consequence of the rise of Netflix, Payne shows that, contrary to popular belief, the company's downfall was primarily due to internal mismanagement and strategic failures. The company didn’t give customers what they wanted (e.g. popular new releases frequently out of stock and being heavily dependent on late fees for revenue), which made them willing to switch to video-on-demand.

Rob Johns. Takeover: Explaining the extraordinary rise of the SNP. Biteback Publishing, 2016.

Such as:

https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2021/jul/02/muslim-voters-feeling-unprecedented-discontent-labour-batley-spen

https://www.theguardian.com/politics/article/2024/may/31/labour-will-struggle-birmingham-ladywood-voters-gaza-poverty

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/labour-keir-starmer-muslim-gaza-israel-palestine-b2540759.html

For more on this, see:

Dan M. Kahan et al. “The Polarizing Impact of Science Literacy and Numeracy on Perceived Climate Change Risks.” Nature Climate Change 2/10 (2012): 732-735.

April A. Strickland, Charles S. Taber, and Milton Lodge. “Motivated Reasoning and Public Opinion." Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 36/6 (2011): 935-944.

Charles S. Taber, and Milton Lodge. “Motivated Skepticism in the Evaluation of Political Beliefs." American Journal of Political Science 50/3 (2006): 755-769.

"Brexit and Trump melted a lot of people’s brains, but one of the worst side effects is that defending the assumptions about voters that underpin democracy is now seen as (God forbid) ‘populist’ 😱😱😱"

Very interesting post, especially the last section.

«Surveys can show gaps between what voters want and what politicians do, but they don’t tell us if voters care enough about it to change their vote.»

Notorious USA political strategist Grover Norquist espressed this well in a very useful interview in 2006:

https://prospect.org/article/world-according-grover/

“Pat Buchanan came into this coalition and said, “You know what? I have polled everybody in the room and 70 percent think there are too many immigrants; 70 percent are skeptics on free trade with China. I will run for President as a Republican; I will get 70 percent of the vote.” He didn't ask the second question … do you vote on that subject?”

In 2016 that changed.

«Just because someone agrees or disagrees with a policy doesn’t mean it will shape how they vote.»

http://web01.prospect.org/article/world-according-grover

“Spending's a problem because spending's not a primary vote-moving issue for anyone in the coalition. Everybody around the room wishes you'd spend less money. Don't raise my taxes; please spend less. Don't take my guns; please spend less. Leave my faith alone; please spend less.

If you keep everybody happy on their primary issue and disappoint on a secondary issue, everybody grumbles … no one walks out the door. So the temptation for a Republican is to let that one slide. And I don't have the answer as to how we fix that. But it does explain how could it possibly be that everyone in the room wants something and doesn't end up getting it because it's not a vote-moving issue. But on the vote-moving primary issue, everybody's got their foot in the center and they're not in conflict on anything.

The guy who wants to spend all day counting his money, the guy who wants to spend all day fondling his weaponry, and the guy who wants to go to church all day may look at each other and say, "That's pretty weird, that's not what I would do with my spare time, but that does not threaten my ability to go to church, have my guns, have my money, have my properties, run by my business, home-school my kids.”