John Maynard Keynes Can Solve the Tariff Crisis

Build Back Bancor?

Hello there! 😀

You may have seen that international trade has been in the news somewhat recently.

Usually, macroeconomics and the international monetary system would be the most boring Substack post imaginable, but given recent events, I’m not sure this is still the case.

Ever since he came down the escalator in 2015, Trump has made trade (especially the US’s large trade deficit with the rest of the world) into a hot topic. I’ve been ‘doing my own research’ into the subject and – while managing to avoid falling down any rabbit holes about King Charles being a lizard – it turns out that trade deficits and surpluses are way more interesting than I expected.

What if I told you that the problem of international trade imbalances was actually solved 80 years ago at the end of WWII? It’s just that the solution has never been implemented.

In The Battle of Bretton Woods, Benn Steil dives into the background and history of the Bretton Woods Conference, where the foundation for today’s global economic system was laid. It’s also where John Maynard Keynes proposed his (ultimately rejected) solution to the problem of large differences between countries in what they export and import, which could have come in handy right about now.

While this book forms the bulk of the facts/analysis in this article, I would also strongly recommend the following to get your head around what the hell is going on at the moment:

There may currently be a ‘90-day pause’ to the trade war, but that doesn’t mean all the issues that led to it have gone away. The system have/had is (as you’ll see) really sub-optimal. Going back to ‘normal’ will continue to lead to problems for the US and the rest of the world. Changing the system could lead to reduced tensions between countries and more broad-based global economic prosperity.

Given that this is a complicated subject, I thought I’d try to write an accessible, interesting (and hopefully accurate) overview of what’s happening right now – and how a long-disregarded idea from Keynes could not only solve current issues but also lay the foundation for a fairer, more cooperative international system that drives broad-based prosperity.

Why having a large trade surplus is NOT a good thing

In the middle of WWII, the economist John Maynard Keynes starting thinking about what kind of system might prevent global catastrophes like another Great Depression or another world war.

He believed that the economic instability of the pre-war period had played a major role in the political breakdown that followed. In the 1930s, the global economy fractured. Countries raised tariffs to protect domestic industries (as with the US’s Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act), deliberately devalued their currencies to gain an export advantage (as Britain did when it abandoned the gold standard in 1931) or hoarded gold rather than spending or investing it (as France and the US did).

Crucially, there was no effective mechanism to resolve big differences between what countries exported or imported in a neutral and pre-agreed way that would benefit the overall global economy.

If peace was to last, Keynes argued, the post-war economic system would need to be more stable, more cooperative and less prone to the kind of boom-and-bust cycles that fuelled the extremism, violence and ‘beggar-thy-neighbour’ of the 1930s.

Keynes believed that it wasn’t trade itself that had caused the instability, but trade imbalances. That is, the persistent gap between what some countries exported and what others imported.

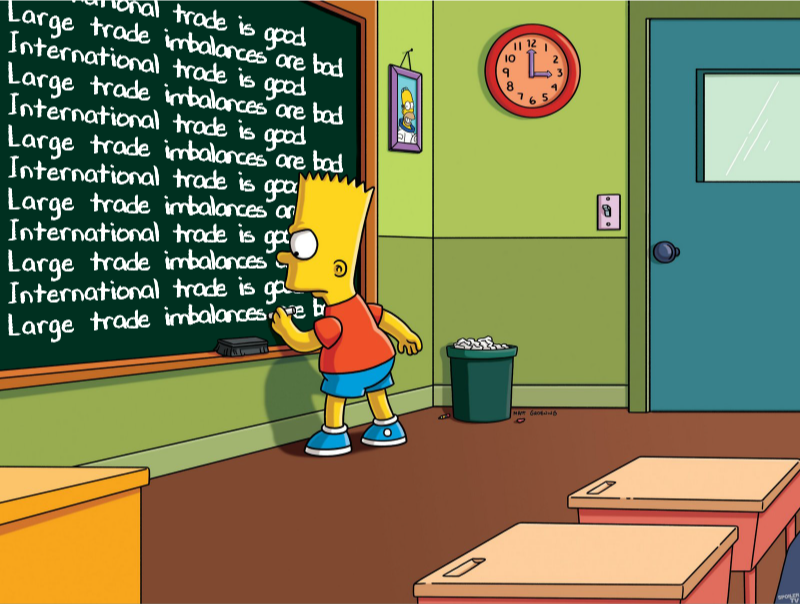

Economists are right when they say that international trade as a whole is good and positive-sum. Countries can specialise in what they’re good at, trade with each other and everyone can benefit.

This logic applies to overall trade itself, but not to the balance of trade.

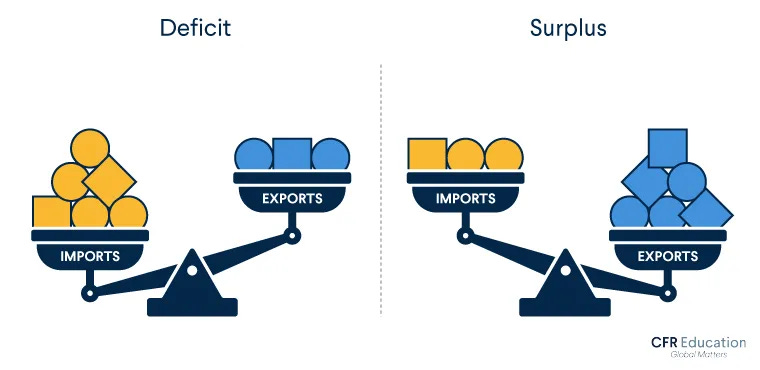

In the global trade system, one country’s surplus is always another’s deficit. When you add up all the trade in the world in a year (whether overall trade is large or small, increases or decreases) the total value of what’s exported has to equal the total value of what’s imported.

So if some countries are running surpluses, others have to be running deficits. The global ledger has to balance.

At first glance, a trade surplus looks like a win. A country is selling more to the world than it’s buying. It’s bringing in money, creating jobs and growing its economy. What could be wrong with that?

The problem is that what’s good for one country isn’t good for the system as a whole. Because we live in a connected global economy, over time imbalances hurt everyone.

Surplus countries are essentially reducing demand in the global economy. They sell goods and services but don’t purchase enough from other countries in return. This means that the overall demand for goods and services around the world stays lower than it could be. Global economic growth slows down because there’s less buying and selling happening around the world. As a result, the whole system is less dynamic.

Surplus countries also often maintain their position by suppressing domestic consumption. Their citizens are working hard to produce goods that are shipped overseas, rather than enjoying the full fruits of their own labour. It’s a bit like saving obsessively without ever enjoying your income. But what’s good for an individual or a household (saving more) can be bad when everyone does it at once, because it reduces overall demand and slows the economy down.

Countries that rely heavily on export-led growth become vulnerable if their trading partners slow down or erect barriers. A global recession, a shift in demand or a tariff war (!!!) can hit them hard. Because their economies are geared toward selling abroad, they have fewer options if foreign markets dry up because they do not have as developed of a domestic economy.

Meanwhile, countries running deficits face the opposite set of problems. To pay for their excess imports, they must borrow or sell off assets, leading to rising debt or a loss of control over domestic industries. Over time, this weakens their economic resilience. As domestic producers get outcompeted by imports, industries shrink or disappear. That means job losses, a hollowed-out industrial base, and the loss of skills and supply chains needed for future growth. It also leaves deficit countries more dependent on imports for essential goods, making them also vulnerable if trade is disrupted by, for example, a global pandemic.

Keynes was also troubled by the fundamental difference in how the international system handled imbalances. Deficit countries faced pressure to adjust through devaluation, unemployment and/or austerity. However, surplus countries faced no equivalent pressure to reduce their surpluses. They could accumulate indefinitely with no penalty. This imbalance could lead to an ongoing cycle of economic stagnation for some, while others grew richer.

As we are seeing right now (and as Keynes saw in the 1930s), when global trade becomes significantly unbalanced, it eventually becomes a political issue. People in deficit countries (rightly) begin to grow resentful of job losses. People often blame foreign competition for their economic struggles, which can fuel protectionism and eventually hostilities between countries.

Meanwhile, surplus countries often view themselves as virtuous, efficient and disciplined, whilst at the same time casting deficit countries as reckless or lazy. This moral framing fuels resentment. It ignores the structural nature of trade imbalances and paints an unfair picture, where deficits are always and only the result of poor choices rather than the inevitable counterpart to someone else’s surplus. Over time, this narrative deepens divisions, making international cooperation harder.

This doesn’t mean trade itself is zero-sum. But when the flow of trade becomes unbalanced for too long it creates pressure points in the system.

Just like in any healthy relationship (whether family, friends or partners) things work best when there’s a sense of balance. When both sides feel like they’re giving and getting in return, the relationship can grow stronger over time. But if one person is always giving and the other is always taking, it starts to wear thin. Even if no one’s doing anything ‘wrong’ the imbalance itself creates tension. Eventually, it leads to frustration, resentment and breakdown.

The same goes for the global economy. No system can keep working smoothly if the flow of give-and-take gets too one-sided for too long.

Bancor and the International Clearing Union

So Keynes proposed a redesign of the global system. At the heart of his vision was a brand-new kind of money which he called the Bancor.

The Bancor would not replace the money people used in everyday life in the shops. Americans would still use the dollar, the UK the pound, Japan the yen etc.

Instead, the Bancor would exist only at the international level. It would be used exclusively by countries (not individuals or companies) and only for keeping track of who was buying and selling what across borders.

To manage this system, Keynes proposed an International Clearing Union (ICU). Every country would have an account with the ICU, measured in Bancors. The ICU’s job would be to record every export and import between countries.

If your country exported something to another country, it would earn Bancors which would be credited to your ICU account.

If your country imported something from another country, it would spend Bancors from your ICU account.

Over time, this would create a running balance sheet for each country. Countries that sold more than they bought would accumulate Bancors (a surplus). Countries that bought more than they sold would owe Bancors (a deficit).

So far, so straightforward. You export, you earn. You import, you spend.

However, the key part of Keynes’s system was that the Bancor and the ICU were designed not just to be scorekeepers, but to actively promote balance and fairness in global trade in order to ensure that the world economy remained stable and cooperative.

The ICU would not only track trade imbalances, it would also take steps to make sure no country ran a permanent and large surplus or deficit.

If a country’s Bancor account went too far into deficit, the system would automatically begin to apply pressure. Its currency would be gradually devalued relative to the Bancor, making its exports cheaper and its imports more expensive. This natural adjustment would help restore balance over time, because other countries would find its goods more affordable, boosting exports, while domestic consumers would be less inclined to buy imports. The deficit would begin to close.

But what made Keynes’s proposal so different and radical was that the same principle would be applied to countries running persistent surpluses. Their currencies would be automatically revalued upwards to make their exports more expensive and their imports cheaper. Any country whose surplus exceeded a set threshold would be charged a fine in order to incentivise it to put its excess earnings back into circulation, rather than sitting on them as hoarded reserves. This would encourage them to consume more, invest abroad or stimulate domestic demand to offset the imbalance.

In other words, the system treated both excessive deficits and excessive surpluses as problems.

The Bancor system was like a thermostat for the balance of trade. If things got too hot (too big of a surplus) or too cold (too big of a deficit), the system would automatically adjust the temperature by tweaking currencies. Without drama or shouting matches, it would be a quiet, ongoing correction to keep the room comfortable for everyone.

Keynes’s proposed system didn’t try to completely eliminate trade imbalances but to discourage extreme, persistent imbalances and to ensure that the burden of adjustment was shared. It acknowledged that for international trade to be sustainable, value has to circulate.

Trade itself was not treated as a problem. An ideal system would be one that would do two things at once: maximise international trade but minimise trade imbalances. When trade is more or less balanced, everyone feels like they’re getting something out of it, because they actually are. Each country is contributing and receiving in return.

But when trade gets too far out of balance for too long, resentment builds. People start to feel like the system is unfair and, often, they’re right. That’s when cooperation breaks down and politics turns inward. For Keynes, that wasn’t just bad economics, it was a threat to global peace.

By building in automatic adjustments and mutual responsibilities, the Bancor and ICU system would have relieved the strains that build up when global trade becomes too one-sided. And in doing so, it might have helped prevent the very kind of economic breakdowns that lead, eventually, to political ones.

Why the Bancor Was Never Adopted

In 1944, as WWII neared its end, delegates from Allied nations gathered in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, to design the postwar global economic system. The world had been through a catastrophic depression and two world wars within the span of three decades. The hope was that, this time, peace could be built not just on diplomacy and treaties, but could be underpinned by a stable and fair international economy.

This was where Keynes proposed his idea of a new international system built around the Bancor and ICU to keep global trade balanced.

Keynes came as head of the British delegation, but the real power at the table was the United States. By 1944, the US economy was by far the world’s largest. Its industrial base was booming, its gold reserves were enormous and its wartime economy had made it the main creditor to the rest of the world.

At the same time, Europe was shattered and Britain was deeply indebted. America was the only country left with the financial weight to shape the new system.

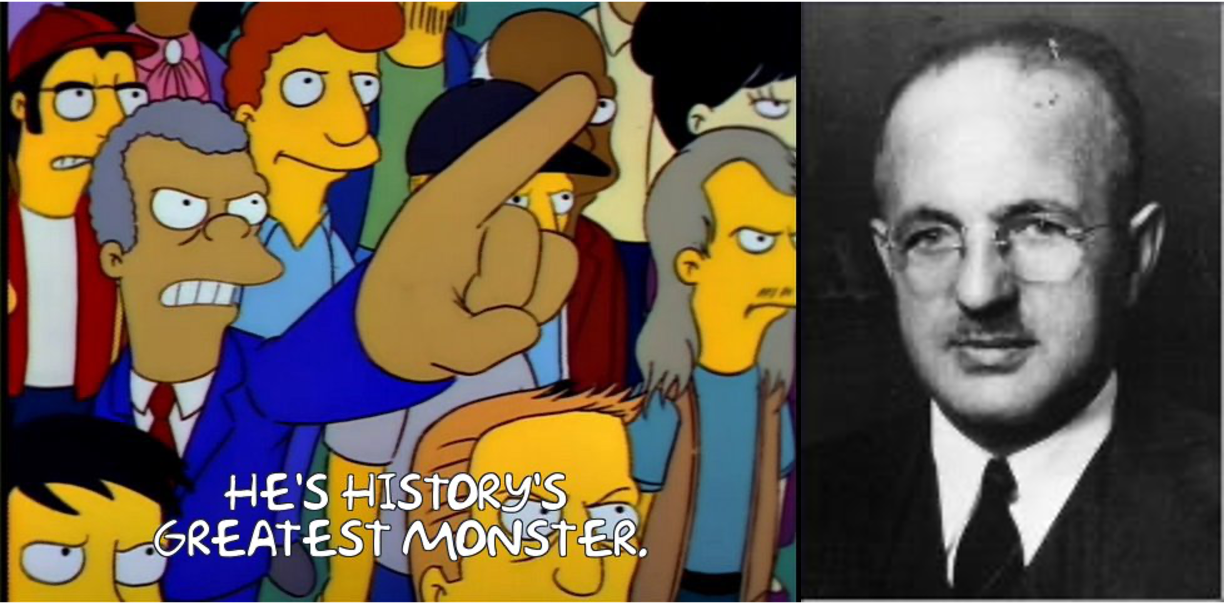

The man representing US interests at Bretton Woods was Harry Dexter White, a senior official at the US Treasury (who was also later exposed as a Soviet spy) who had a very different vision. Where Keynes proposed a neutral, supranational currency (the Bancor) to prevent any one nation from dominating global trade, White proposed something much more straightforward: use the US dollar as the anchor of the international system.

This was not an unreasonable suggestion from the American perspective, because the US was the dominant economic power and its currency was stable. However, it was also fundamentally short-sighted, because it assumed that America’s trade surplus and economic dominance would last indefinitely.

Under White’s plan, countries would fix the value of their currencies in relation to the dollar, and the dollar itself would be convertible into gold at a fixed rate ($35 per ounce). This became known as the Bretton Woods system.

From 1945 to the early 1970s, the global monetary system functioned like this:

Each country would peg its currency to the US dollar.

If your currency got too weak or too strong, your central bank would intervene by buying or selling dollars to keep it within the fixed band.

In turn, the US promised to convert dollars into gold for any central bank that asked.

This meant that the dollar became the de facto global reserve currency.

In theory, this created a stable, rules-based system. Countries could trade with each other knowing that exchange rates would stay broadly stable. There would be no currency wars or chaotic devaluations. It was a system that combined the predictability of the gold standard with a degree of national flexibility.

And, for a while, it worked great. The post-war decades came to be known as the ‘Golden Age of Capitalism.’ In France, they called it Les Trente Glorieuses (the thirty glorious years). West Germany (Wirtschaftswunder), Italy (Miracolo Economico) and Japan (Kōdo keizai seichō) all called it an economic miracle. These were years of booming growth, rising living standards and secure welfare states. Across the West, unemployment was low, wages were rising and middle-classes were expanding.

But the problem of imbalances did not go away. Even with Bretton Woods, countries that ran persistent trade deficits found themselves under pressure. They would start losing dollars (and thus gold reserves) and eventually they’d be forced to cut spending, raise interest rates or implement a currency devaluation.

The UK struggled with chronic trade deficits and declining reserves. Again and again, it had to impose austerity measures, borrow from the IMF and devalue the pound –most (in)famously in 1967.

However, the United States was in a unique position within this Bretton Woods system: it was the anchor.

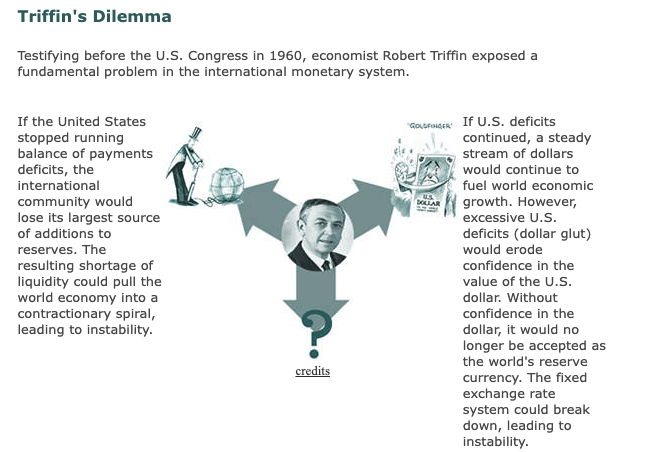

All other currencies were pegged to the dollar and the dollar, in turn, was pegged to gold at a fixed rate. This central role created a big problem that economist Robert Triffin pointed out in the 1960s, now known as the Triffin Dilemma.

Here’s the core of the dilemma: as the global economy grew and international trade expanded, other countries needed more and more US dollars to participate. They needed dollars to settle trade, maintain their currency pegs and hold as reserves.

But there was only one main way for those dollars to get out into the world: the United States had to run trade deficits. That meant buying more from the rest of the world than it sold, such as by importing goods, investing abroad or lending money to other countries. This is how dollars flowed out of the US and into the global system.

However, the more dollars the US sent abroad to support the growing global economy, the more fragile the system became. Why? Because the US had promised that anyone holding dollars could exchange them for gold at $35 an ounce.

As more and more dollars piled up overseas, people began to worry: what if everyone tried to cash in those dollars for gold? The US didn’t have nearly enough gold in reserve to cover all the dollars in circulation.

To keep the system going, the US had to supply the world with dollars but doing so put its promise to back those dollars with gold at risk.

Eventually, something had to give.

The Nixon Shock

By the late 1960s, as the US issued more dollars, confidence in the dollar’s convertibility into gold began to erode. The issue was simple: the US simply didn’t have enough gold in reserve to back all the dollars it had put into circulation.

French President Charles de Gaulle became increasingly concerned about America’s growing trade deficit and the flood of dollars circulating globally. In February 1965, de Gaulle announced that France would demand gold in exchange for dollars. It was like telling someone who gave you IOUs that you now want the actual money.

De Gaulle literally sent a warship (!!!) to get the gold. The US couldn't refuse France’s request without breaking international agreements. So the gold was transferred, but tensions remained high. Other countries followed France's example and began demanding gold too.

In the face of all this, President Nixon made a historic announcement in 1971. He told the world that the US would (*cough*) ‘temporarily’ suspend the convertibility of the dollar into gold. In practice, this meant that foreign governments could no longer exchange their dollar reserves for gold at the fixed rate of $35 per ounce which was the central pillar of the Bretton Woods system.

Nixon justified this move by citing ‘speculative attacks’ on the dollar and the need to protect American economic interests. But this masked the actual reality: the US did not have enough gold to cover the volume of dollars circulating abroad. Nixon chose to act unilaterally rather than risk a catastrophic run on US gold reserves.

This event, now known as the ‘Nixon Shock’, effectively marked the end of the Bretton Woods system. The gold-dollar peg was its foundation and once that link was broken, the entire structure unraveled. The world moved into a new era of fiat money and flexible exchange rates.

Since 1971, the dollar remains the world’s main reserve currency, but there is no formal peg, no gold backing and no international clearing mechanism like Keynes’s ICU.

And so the basic issue that Keynes tried to solve in 1944 remains with us today: a global economy that has no built-in mechanism to correct imbalances, no supranational currency to serve as a fair medium of exchange and no global institution to keep trade cooperative and stable over time.

(As a related aside, please do check out this website to try and work out WTF happened in 1971: wtfhappenedin1971.com)

Enter Donald Trump

Since the Nixon Shock, the global economy has operated under a new kind of system. The dollar wasn’t backed by gold anymore, it became backed by trust (such as the size and stability of the US economy, its military power, its financial infrastructure and its rule of law). That trust turned out to be good enough and the US dollar became the world’s primary reserve currency.

It meant that countries around the world started using the dollar not just for trading with America, but for trading with each other. Dollars became the default currency for buying oil, food and raw materials, as well as for storing national savings, investing in global markets and managing central bank reserves. The dollar became the international language of money.

But those dollars have to come from somewhere. They don’t just magically appear in other countries’ bank accounts. They have to enter the system somehow and the main way that happens is through US trade deficits.

When the United States buys more from the world than it sells, it sends dollars abroad. For example, if the US imports cars from Japan, electronics from South Korea or clothes from Vietnam, American consumers and businesses pay in dollars. Those foreign companies and their governments now hold those dollars.

What do they do with them? Often, they reinvest them back into the US by buying things like US Treasury bonds (which finance US government spending), investing in American companies or simply keeping the dollars as part of their national reserves. This constant cycle is how the rest of the world gets and uses dollars, and it’s how the global economy stays lubricated.

This system has/had benefits for the US and other countries:

The dollar remained supreme because countries needed dollars to engage in trade and to maintain currency reserves. The constant demand for dollars to settle transactions around the world kept the dollar strong and central to global finance. The US (unlike other countries - just ask Liz Truss) could run large trade deficits and accumulate debt without much pressure, because the dollar’s status ensured a steady global demand for it.

Americans enjoyed cheap goods and strong consumption, benefiting from a supply of inexpensive products from other countries. This meant Americans had access to cheaper goods, financing and a higher standard of living.

Export-led economies flourished because they could sell more to the US, earning dollars that they could reinvest in the global economy or use to fund their own growth. The demand for their products was bolstered by the appetite of American consumers.

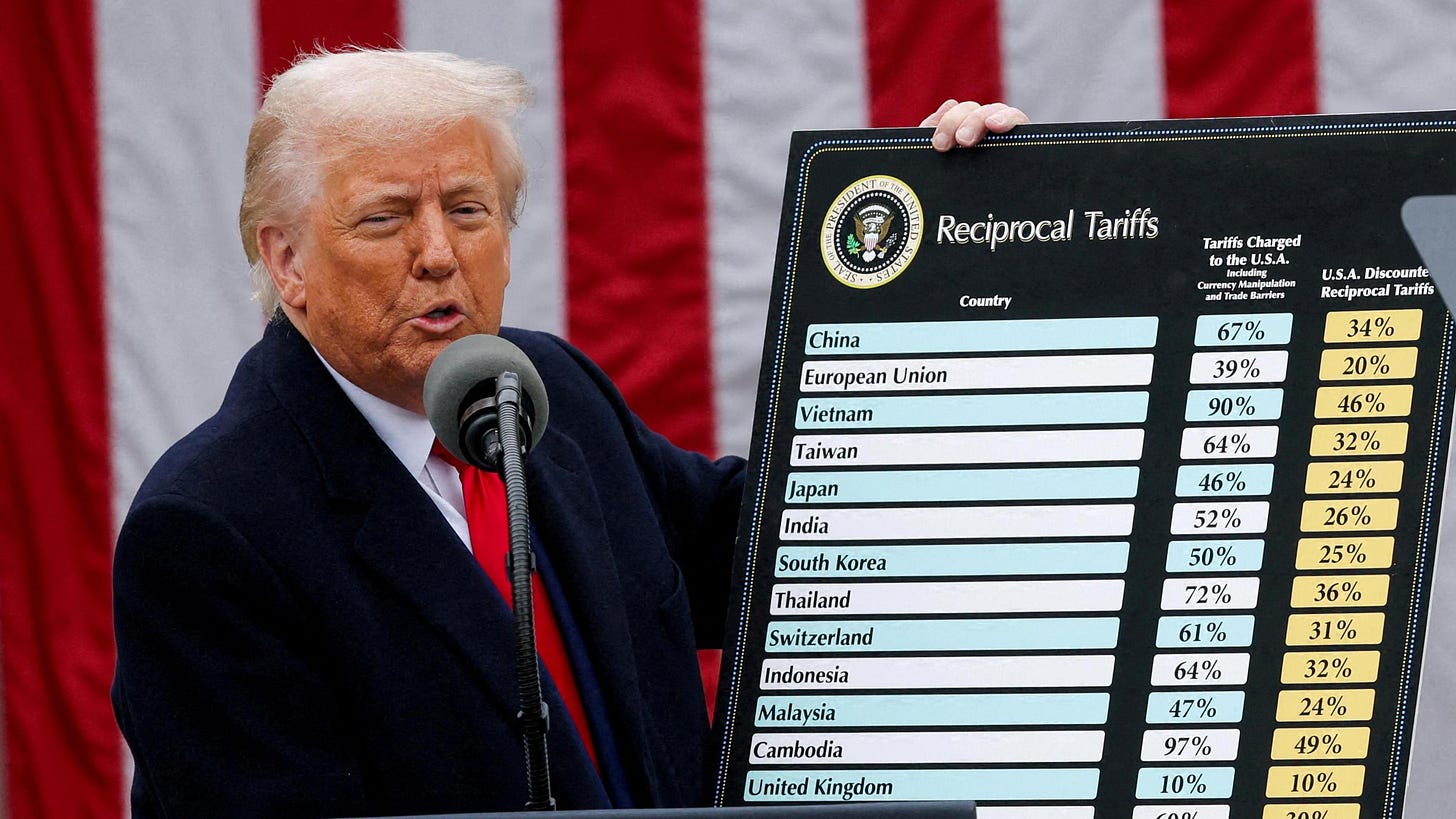

President Trump has long criticised this arrangement and, to be fair to him, there are costs to the US from this system:

US manufacturing declined because the country could import goods more cheaply than producing them domestically. The dollar, boosted by its status as the world’s reserve currency, stayed stronger than it would be otherwise. This made American-made products expensive on global markets and, as a result, US industries found it harder to compete. Companies moved production abroad to stay profitable, leading to factory closures, job losses and a hollowing-out of the country’s industrial base.

Global imbalances grew because the system encouraged persistent trade deficits for the US and trade surpluses for others. Surplus countries amassed dollar reserves, which they didn’t necessarily reinvest in their own economies, while deficit countries accumulated debt. Over time, these imbalances risked reducing overall growth and destabilising the global financial system.

The entire world economy became tethered to US consumer and monetary policy, because the system relied so much on dollars and American consumption to drive global trade. Additionally, the US could influence global markets through its monetary policy, which had ripple effects on economies around the world, making them vulnerable to shifts in US economic strategy.

Trump’s main complaint is that trade deficits are proof that America is being cheated and he wants to eliminate the US trade deficit. But that deficit isn’t a bug, it’s a feature of the post-Nixon dollar system. The world needs the US to run a deficit because that’s how it gets the dollars it depends on.

Think of the US like the central water pump in a village. It pulls in goods from the rest of the world but in doing so, it pushes dollars out. Those dollars flow into every corner of the global economy. The trade deficit is what keeps that pump running.

Now imagine what happens if you shut off the pump.

If Trump succeeds in cutting the US trade deficit (slapping tariffs on imports, rewriting trade deals, pushing companies to bring production back home) fewer dollars will flow out into the world. Countries that rely on exporting to the US will earn less. Their dollar inflows will shrink. Their reserves will start to decline.

At first, this might look like a win for American manufacturing. But over time, it creates a much bigger problem not just for other countries, but for the US itself.

If other countries stop earning as many dollars, they may not be able (or willing) to keep buying US government debt. That could make it more expensive for America to borrow money, pushing up interest rates and limiting public investment.

The dollar’s dominance has been a pillar of US global power for decades. It lets them borrow cheaply, influence global markets and impose sanctions with real bite. But all of that depends on the rest of the world wanting and needing dollars. If America stops supplying them, the rest of the world may eventually stop relying on them.

Trump has never been invested in preserving the architecture of post-WWII American hegemony. For him, the dollar’s role in the global economy isn’t a strategic asset to be protected.

But he will care (or at least feel the political heat) if the consequences of undermining that system show up in the domestic economy. If the world starts demanding fewer dollars because the US is no longer running trade deficits at the same scale, it could mean:

Less demand for US government debt: Foreign countries, particularly surplus nations, recycle their dollar earnings by buying US Treasury bonds. That keeps American borrowing costs low.

If that demand falls, the US may have to offer higher interest rates to attract buyers making it more expensive for the government to borrow.

Higher borrowing costs would ripple through the economy, pushing up everything from mortgage rates to business loans, and straining government budgets.

This could squeeze domestic investment: If the U.S. government has to pay more just to service its debt, there’s less fiscal room for infrastructure, social programs or industrial policy – all things Trump says he wants to expand.

Trump’s approach may be remembered as the second great rupture after the Nixon Shock. 1971 ended the gold-dollar link, but 2025 could end the open-dollar trade link.

The Core Problem: Imbalances Without Correction

The chaos of 2025 isn’t just about unfair trade deals or supply chains. It’s not even just about Trump himself, where going back to ‘normal’ would make everything great for the US and the rest of the world.

It’s about an international system that lacks any real mechanism to manage imbalances peacefully. It’s not just a trade war, it’s a system failure.

And it’s exactly the kind of failure that the Bancor and ICU were designed to prevent.

At the heart of Trump’s tariffs is the complaint that America buys far more than it sells. It runs huge trade deficits while other countries accumulate surpluses.

But the reason these imbalances persist for years/decades is because there’s no mechanism that encourages/nudges/shoves surplus countries to adjust. The burden always falls on a deficit country.

Think of the French Ligue 1 football league. Paris Saint-Germain (PSG) win almost everything, every year. That’s great for PSG, they get trophies, can buy all the best players and can create a team that is much better than any other in France.

But the other teams? The league as a whole becomes weaker, less watched and less invested in. What’s good for PSG turns out to be bad for the collective. Sure, some other teams can have a good season (such as Lille winning the league in 2020-21) but these are the exceptions. PSG will always dominate because there is no way to correct the imbalance.

Like Ligure 1, the current system that Trump is railing against lacks the means to correct persistent imbalances.

Now contrast Ligure 1 with the NFL. The draft system and salary cap are designed to stop any one team from dominating for too long.

When a team does well in a season, their players demand more money in contract renewals. However, the salary cap means that the team can’t keep (i.e. pay) all of their best players. Rather than being rewarded for their success, the system limits how well the team can do going forward. These players have to be released/traded and move to less successful teams who are able to pay them what they are worth. This, in turn, increases the new team’s quality and prospects for the upcoming season.

When a team does badly in a season, they get the top choices of the best young players in the NFL draft. Instead of being punished for being terrible, they are rewarded. By gaining great young players for their team, this also helps increase the new team’s quality and chances in the new season.

These mechanisms may frustrate dominant teams but it keeps the whole league competitive. It means every fan feels like their team has a shot. Most importantly, it has helped make the NFL one of the most successful and valuable leagues in the world. What might seem detrimental to individual teams ultimately benefits the collective because automatic, agreed-upon rules correct imbalances and apply equally to everyone.

The Bancor-ICU system would function like the NFL in the global economy. It would solve the issue of persistent imbalances with automatic corrections (like the salary cap and NFL draft do). By implementing systematic corrections to prevent excessive dominance or weakness by any single economic player, it would help create a more balanced, sustainable global economic system.

A Bancor-ICU World

So what would life in a Bancor-ICU world be like? Here a realistically positive version of what could occur.

1. Target both sides of the imbalance

Today’s global economy expects only deficit countries to ‘fix’ themselves through austerity, currency devaluation or tariffs. But under Keynes’s plan:

Surplus countries would face rising charges on their excessive Bancor balances if they failed to recycle them through investment or imports.

Deficit countries would be given time and space to adjust gradually without being forced into recession or retaliation.

This would completely change the logic behind Trump’s tariffs. Instead of trying to eliminate the US trade deficit by taxing imports, ICU rules would have already pushed surplus nations to adjust fairly, and within a multilateral and transparent system.

2. End the dollar’s global burden

The post-Nixon system relies on the US dollar as the world’s reserve currency. That means other countries need dollars to trade and the only way the world can get them is if the US runs a persistent deficit.

Trump says he wants to eliminate the trade deficit and keep the dollar as the global standard. But those goals contradict each other. The moment the US stops supplying dollars to the world, the whole system seizes up. Bancor breaks this contradiction:

Trade would be settled in Bancors, not national currencies.

The world wouldn’t rely on the US to provide liquidity.

The US wouldn’t be structurally forced into a trade deficit, nor would it bear the burden of currency manipulation or reserve hoarding by others. Trump’s stated goal of reducing the trade deficit could become much more achievable under such a system, as the global economy would no longer rely on the US as the key provider of currency.

3. De-escalate trade conflicts

The ICU was designed to prevent exactly the kind of tit-for-tat escalation that we are seeing right now. Countries wouldn’t need to defend their trade position unilaterally, because imbalances would be handled through an automatic clearing system.

Imagine the current situation playing out under Bancor:

Instead of tariffs, a country like China would face a rising cost for running massive surpluses.

Instead of unilateral accusations of ‘cheating’ there would be clear rules governing adjustment.

Instead of tariff wars, there would be structural incentives to move toward balance before things reached crisis levels.

Crucially, this all would have been done gradually over years, with adjustments made at a measured pace rather than the violent swings we’ve seen recently.

4. Stabilise prices and global supply chains

Tariffs don’t just hurt exporters, they raise prices across the board. American consumers will pay more for everything from cars to coffee. Global supply chains built over decades are suddenly breaking.

Bancor would’ve created a far more stable trading environment:

Exchange rates would be more predictable.

No single currency would swing wildly.

Countries wouldn’t be incentivised to manipulate their currency or engage in beggar-thy-neighbour policies.

In short, companies could plan, invest, and trade without fearing sudden shocks from a tweet or a tariff.

5. Broad-based global economic growth

Imagine a situation today where we had a system that encouraged surplus nations like Germany and China to import (i.e. spend) more. Imagine if we had a system that encourages deficit nations like the US and UK to export more.

This balanced approach would create a self-reinforcing positive cycle:

If surplus countries increased their imports, this would stimulate demand in deficit countries.

This increased demand for deficit countries’s products would enable them to grow, generate wealth and expand their export capabilities.

Surplus countries would enjoy more a wider variety of goods and services, as well as increased domestic consumption and a higher standard of living for their citizens.

As deficit countries became more prosperous, they would continue to export but a balanced, sustainable manner.

Surplus countries would still benefit from trade, but in a mutually advantageous way.

Both sets of economies would become more resilient against external shocks.

The result would be widespread economic growth, driven by trade that is balanced, not just by the excesses of one nation’s exports or another’s imports. This creates the kind of interdependence that leads to shared prosperity rather than the kind of unbalanced, unsustainable growth seen today.

What’s the Hold Up?

While the logic behind a modern Bancor and ICU is compelling, implementing such a system is another matter entirely. The idea may be elegant on paper, but in practice it runs headfirst into major economic, political and logistical obstacles.

1. Punishing Success

The most fundamental critique of the Bancor system from economists is that it redefines trade surpluses as a problem and proposes penalties for them.

In standard economics, a surplus is seen as a sign of competitiveness, efficiency and prudent economic management. Under the Bancor system, however, this success becomes a liability. The longer they hold onto a trade surplus without recycling it back into the global economy, the more they pay.

This is intentional. The Bancor/ICU framework assumes that imbalances are a two-sided problem and that both creditors and debtors bear responsibility. But many economists argue this penalises discipline and rewards profligacy.

Why should a country that makes high-quality goods and saves more than it spends be compelled to fix the problem of another that overspends and under-produces? It’s a critique rooted in classical liberal economic thinking and one that remains dominant in many finance ministries (and university economics departments) today.

2. Global Coordination Is Nearly Impossible

Even if the economic debate could be won, the political barriers are even higher.

For a Bancor/ICU system to work, nearly every major economy would have to opt in and agree to strict rules governing trade balances, currency convertibility and reserve management. That’s not just unlikely, it’s historically unprecedented.

The system requires:

Abandoning reliance on national currencies in trade settlement

Agreeing to automatic penalties for excessive imbalances

Ceding economic sovereignty to an international institution

In a world that’s increasingly multipolar, fragmented and mistrustful, this is hard to imagine. Countries like China, India, the US, the EU and the Gulf states have wildly different priorities, economic structures and strategic incentives. The current system is also good for surplus countries, so what incentive do they have to change something which advantages them?

A universal opt-in system with real teeth would require the kind of global political alignment that hasn’t existed since WWII and has arguably never existed at all.

And partial adoption won’t cut it. If key economies refuse to participate, the ICU loses legitimacy and with it, the power to enforce balance.

3. Why Would the US Surrender Dollar Supremacy?

The dollar’s role as the world’s reserve currency confers enormous benefits to the US, as we’ve seen. Even from Trump’s perspective, moving to a neutral global clearing system would mean voluntarily giving up a huge geopolitical advantage.

It would also mean the US trusting that a new system would be governed fairly. In today’s climate of strategic rivalry with China, resurgent industrial policy and economic nationalism, that’s a non-starter.

Without the US, the system wouldn’t work.

4. How Would You Even Build It?

Let’s imagine that the political stars align and the major economies agree to create an ICU. Even then, the project would face staggering logistical challenges. Establishing this system in the 21st century would require:

A new global currency unit (the Bancor), backed by real assets or a basket of national currencies

An international clearing institution to track all cross-border trade, enforce balance rules and levy charges on surplus/deficit positions

Integration with central banks, commercial banks, trade settlement systems and reserve management policies around the world

A legal framework governing disputes, defaults, sanctions and interventions

Mechanisms to prevent manipulation, capital flight or parallel markets

Technologically, some of this might be easier today than in 1944. But the scale of institutional design, legal harmonisation and operational overhaul is immense.

5. How Do You Prevent Cheating?

Even assuming global buy-in and technical implementation, the ICU would face the perennial problem of all international regimes: what happens when countries cheat or defect?

Some scenarios:

A surplus country covertly makes its deficit/surplus seem smaller than what it actually is.

A deficit country keeps borrowing without making reforms or simply refuses to settle up when limits are reached.

A major power uses military or financial leverage to opt out of ICU penalties, or pressures smaller countries to ignore rules.

The ICU would have no sovereign enforcement power. It could threaten exclusion, but it can’t compel behaviour. Without a credible threat of enforcement and real consequences for non-compliance, the incentives to follow the rules erode over time.

This is especially dangerous in a system that relies on mutual discipline. If one major country breaks the rules and gets away with it, others will soon follow.

6. What About Public Opinion?

Beyond the economics and geopolitics, there’s the public opinion hurdle to overcome. The idea of an ‘international currency’ or a ‘global monetary authority’ would (rightly) trigger deep suspicion, particularly among the growing number of people who distrust supranational governance. Even a system as boringly technical as Bancor would invite talk of ‘global elites’.

Ironically, the only political figure with enough credibility to implement such a system might be Donald Trump. Precisely because of his unimpeachable anti-globalist credentials, he could sell a new global monetary arrangement in a way that no technocrat or liberal internationalist ever could.

Trump could frame it not as surrendering American sovereignty, but as reclaiming monetary fairness and ending the cycle of ‘America getting ripped off’ by global trade. By shifting the burden of adjustment to surplus countries, he could position the Bancor system as a way of defending American workers, restoring balance and making international rules work for the US rather than against it.

This may sound paradoxical, but it speaks to the deeply political nature of any reform. Ideas only move when the right messenger carries them and when they can be sold to domestic populations in language that resonates with national interest.

Build Back Bancor?

Trump’s tariffs have now – at time of writing – been given a ‘90-day pause’. But this doesn’t mean the crisis is over. If anything, it has helped highlight the deeper flaw in the global trade system: we still have no reliable way to manage large, persistent imbalances between countries.

As I hope you’ll have seen, going back to the post-Nixon Shock ‘normal’ would be a return to a system that still rewards surplus hoarding, overly penalises deficit countries and relies too heavily on the US dollar.

Keynes saw all this coming. His Bancor-ICU proposal wasn’t about restricting trade, but about making it sustainable. A neutral global unit of account, automatic adjustment mechanisms and shared responsibility for balance would’ve made the system fairer, more stable and more cooperative.

Keynes was writing in the shadow of the 1930s with economic collapse, extremism and resentments between nations that ultimately ended in war. His goal wasn’t just to fix trade imbalances, it was to create a system that made global cooperation not only possible, but natural. That doesn’t mean we’re now destined for World War III. But it does mean we’re playing with fire by sticking with a system that breeds mistrust, encourages hoarding and leaves some countries feeling permanently short-changed.

The Bancor and ICU were intended to prevent exactly this scenario. With such a system in place, countries wouldn’t need to resort to tariffs or unilateral actions to protect their economies.

We ignored that path in 1944. We made something else work for a while but now it’s faltering. In 2025, it’s worth asking the question we’ve avoided for 80 years:

What if Keynes was right all along?

«Europe was shattered and Britain was deeply indebted. America was the only country left with the financial weight to shape the new system.»

from Andrew Marr, "History of modern Britain") “an angry Keynes wrote back to his mother: ‘They mean us no harm but their minds are so small, their prospects so restricted, their knowledge so inadequate, their obstinacy so boundless and their legal pedantries so infuriating. May it never fall to me to persuade anyone to do what I want, with so few cards in my hand ... I am beginning to use up my physical reserves.’”

«proposed something much more straightforward: use the US dollar as the anchor of the international system. This was not an unreasonable suggestion from the American perspective, because the US was the dominant economic power and its currency was stable.»

The reason why it was made was that the USA businesses knew that the other countries wanted to buy american goods (oil included) and USA businesses wanted to be paid in a currency that other countries or an international fund could never print at will, so they demanded that the international currency be the dollar (which only the USA could print at will). Which is quite ironic in this era where all countries including the USA want(ed) to buy chinese goods.

«As Europe and Japan recovered, they became more competitive and began exporting far more to the US. At the same time, US companies were investing overseas, US consumers were buying more foreign goods and US government was spending abroad (eg Vietnam War). [...] All of this pushed dollars out, not because of a master plan but because of demand and behaviour.»

Perhaps not a “master plan” but the intentional pursuit of some goals by various sides. One of the goals was to prevent the further electoral rise of the left in some countries, for example. But perhaps "unintended consequences" applies mostly, but only up to the end of the 1960s. Anyhow I have two interesting quotes from that period:

Violet Bonham-Carter, 14 May 1963 diary entry: «[President Kennedy] went on to describe how [de Gaulle] was now blocking all progress in Europe - in defence, economic, etc. I asked him how he thought this road-block could be broken. He said, 'The root of the matter is that not only you in Britain but we in the USA have now become debtors and not, as we always used to be, creditors. The gold reserve has ebbed at the following rate (he then gave the figures for the last few years).»

In 1961 the post-WW2 "dollar shortage" started to become a "dollar glut":

http://www.mocavo.com/Department-of-State-Bulletin-Volume-Xliv-2/316430/402

«Ten members of the International Monetary Fund today [February 15] announced the formal convertibility of their currencies within the meaning of the articles of agreement of the Fund. The 10 are the United Kingdom, the 6 members of the European Economic Community — that is, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands—together with Sweden, Ireland, and Peru. These actions are heartily welcomed by the United States. They represent the culmination of the efforts of the 10 countries to achieve one of the major objectives set forth in the Fund articles. They constitute further evidence that the system of monetary cooperation embodied in the Fund is working successfully. Most of these countries announced the convertibility of their currencies for nonresidents some 2 years ago.»

That was basically what eventually destroyed the Bretton Woods system for which the IMF had been created, so the latter part of the quote is quite ironic.